"I Had to Come to Terms With the Fact That Kids Are Interesting"

A Conversation with Liana Finck and Sarah Manguso

At some point while I was trying to write a dissertation as a parent of a preschooler and an infant, I attended a workshop from which I remember exactly one thing: Touch Your Project Every Day. We all lead busy lives, one of the organizers explained, and it can be difficult to find long stretches of time to focus and work through such a large and in depth piece of writing. There may be days or weeks when doing anything at all feels impossible but if you can find a way to Touch Your Project Every Day, you’ll never be so distant from it that you can’t find your way back.

That line has stayed with me over the years, a mantra as I slogged through dissertation chapters and then later popping into my head sporadically while I nursed newborns, entertained kids over school vacations, and oversaw pandemic era crafts/Mo Willems drawing lessons. Sometimes it felt like a comforting reminder that I could have something else going on besides making edible play doh and other times it felt more like a haunting. Every so often, it was actually helpful, like when I wrote this essay bit by bit by bit in the interstices of 2020/2021. But I thought of it most when I was not touching any projects besides my children. Or, rather, as they climbed all over me and I had to consider that perhaps I was, so to speak, the project. That we were each other’s projects.

And isn’t it so hard, when you’re covered in children, to separate the projects, the kids you’re trying to raise and the art you’re trying to make? I’m always so interested in that overlap, partially because kids produce such good material. They’re existentialism machines. They access very easily and naturally the mental landscapes most conducive to art making. Who am I? How am I supposed to exist among other people? What is the meaning of this rock?

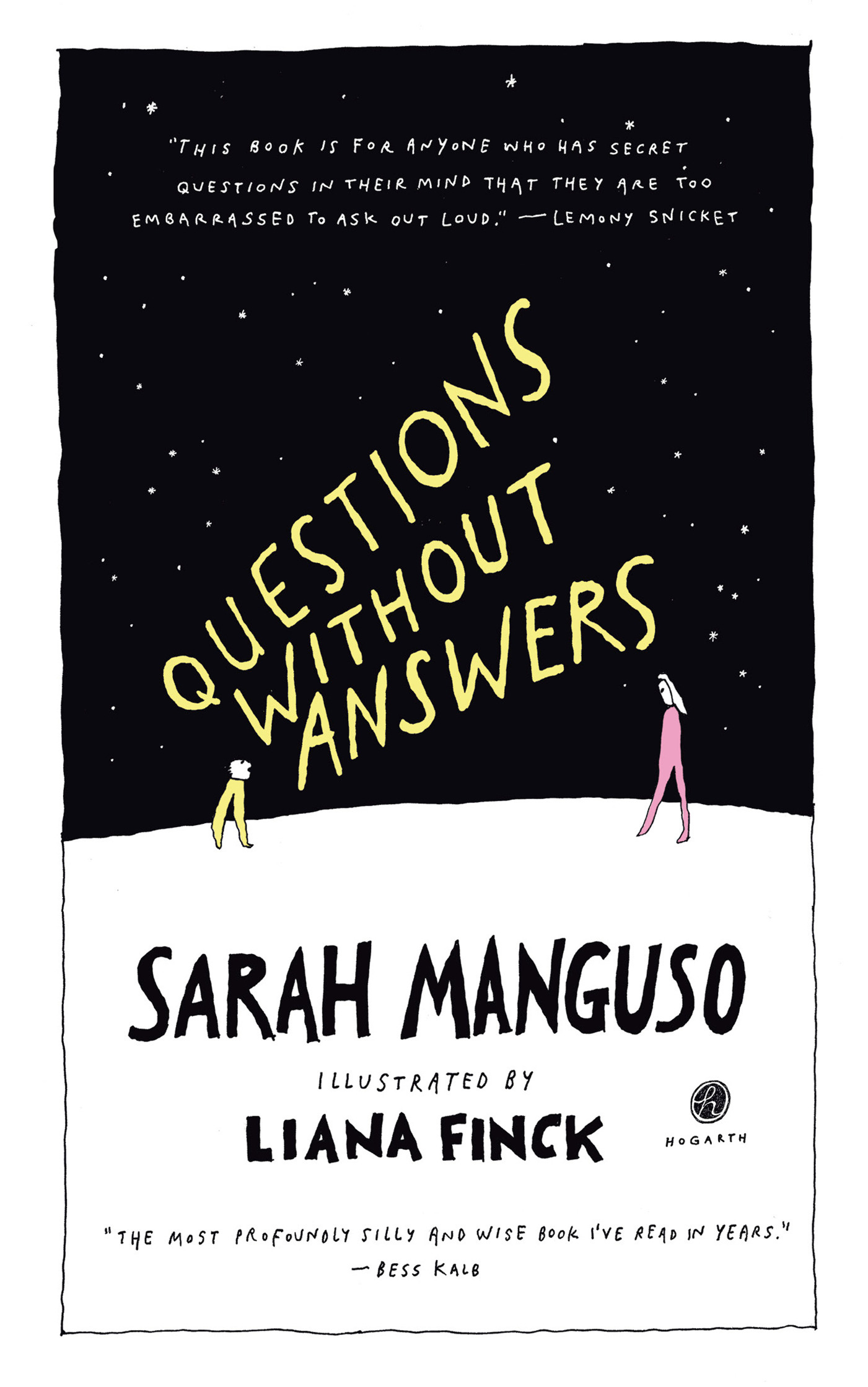

In 2021, the writer Sarah Manguso created a Twitter account and posted a single tweet: “What’s the best question a kid ever asked you?” Within a few weeks, she had hundreds of responses which she then curated, along with some of her own son’s questions, for the book that became Questions Without Answers (use that link and code QA15 for a discount) in collaboration with cartoonist and illustrator Liana Finck. Reading the book naturally reminded me of my own children’s questions (eg “Was I dead when you were a little girl?”/ “Why are ears B’s?”/ “What would you do if you were a squirrel?”) but it made me experience them in a totally new way — not as content but as art.

Aside from Manguso’s wonderful introduction, there’s no room for adult voices in this book, which foregrounds the dignity of the questions themselves. It honors their ability to stand alone and make us think deeply about our lives and the world around us, like any other work of art. Yes, it’s good material, but it doesn’t require an adult interlocutor.

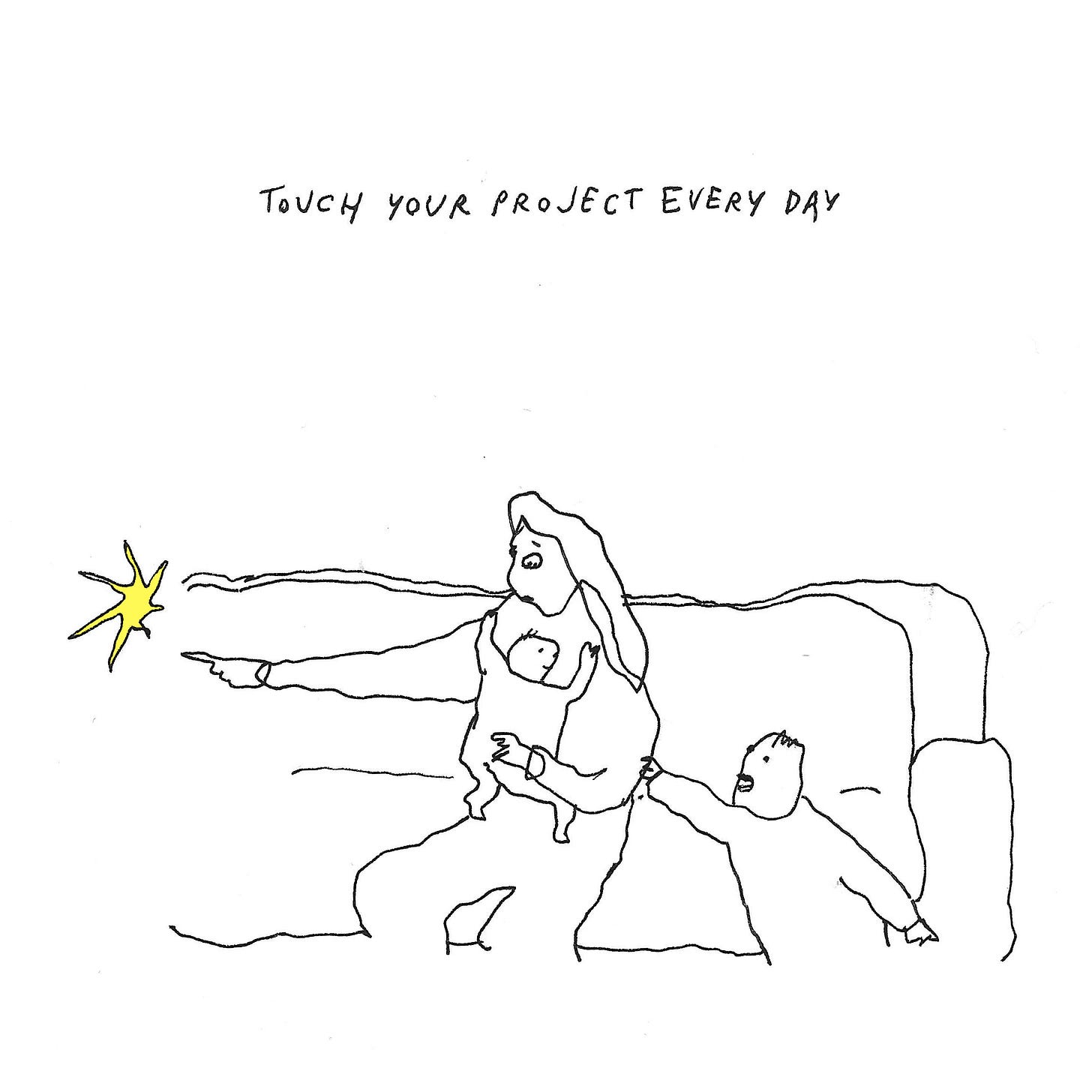

It was a pleasure to talk with Sarah Manguso again, and a delight to get some insight into Liana Finck’s process. I’m so grateful to have an original (!) illustration for our interview, especially since Finck was only two-and-a-half weeks postpartum when we spoke (hero). I have a feeling she’ll be back in this space for a more in-depth conversation about her work before too long. Read on for our conversation about figuring out the right format for a book of questions, using soft power as an antidote to patriarchy, and novel writing as avoidant behavior.

Let’s talk about how this project came to be. Did it originate with your tweet, Sarah?

SM: I guess its public face originated with that Twitter post in 2021, but I was thinking about the origin of the book and, if I'm being honest, I have to say that I've always been interested in the ineffable and the unanswerable. And when I began as a writer, I wrote poems and I was always writing right into the abyss. Describe the abyss; can't do it. Okay, how can we confront it in literature in some way? And I also always wanted to collaborate on a text with an illustrator, and I just never had a good idea. I think a lot of writers of all stripes sort of fantasize about creating the perfect children's book with the perfect illustrator, but it's incredibly hard to write a picture book if you're a text-based or a language-based thinker as I am. I don't really think in images. So anyway, I'd been carrying these proclivities for years and years and years, and then I had my kid and I had a lot of received ideas about what kids were like because I'd seen a lot of ads and crappy entertainment in which kids acted cutesy. And so I thought, kids are cutesy, they're constantly performing for this adult audience. And of course, within a few years, my own kid taught me otherwise, that kids are not like that at all. And I had to come to terms with the fact that kids are interesting.

And super weird. Their minds are wonderful, twisted places.

SM: They are. And I was trying to figure out- somebody asked me, why are kids interesting? What is interesting about a four-year-old as opposed to a 12-year-old who's already trying to be a little adult? And I think it's a combination of things. First of all, the youngest kids are empiricists. They come to the table with no foreknowledge. They have no a priori knowledge of why things are so they're good little scientists. They're constantly testing things. They're learning about the physics of the world, but they don't understand that they're performing childhood for an adult audience so they're guileless. They're not trying to act like children. They're not trying to engage adults in that way, and they also don't understand death yet. So that combination, I think, of perspectives is what makes them so unusual, so weird, and so fascinating.

So what were your criteria for choosing the questions? Was it like you know it when you see it, or did you have certain preconceptions about what you wanted?

SM: It was really fun to sift through the questions. I ultimately hired a couple of research assistants, and we gathered more than 2000 questions.

All from Twitter?

SM: It began with writing my own son's questions down many years ago. He's a teenager now, and I always wanted to do something with it that wasn't really about him. I wanted to be respectful but the work was so good. “Do you like windows?” “What does a gargoyle say?” It was just- I had to write it all down. I see Liana smiling. She's beginning to get material from her elder child.

LF: I never asked which of the questions were from Sarah's kid. It felt rude to ask.

SM: No, I think he would be cool with it. So I was getting like bimonthly reports from my researchers and every other Friday my kid and I would get the list. And I had him sort of workshop them alongside me. It’s fun to involve your kid in your work if you're an artist with kids. And I mean, I don't want to generalize, but my kid seemed interested. Maybe he was just being polite. So there was this sort of ineffable, when you see it quality. And we winnowed that initial really rough list to about 500 questions. And it was at that point that my editor Parisa and I really started getting to work thinking about how to group them. She had the fantastic note to consider grouping them as a kid would. That note is what helped me come up with the eventual section headings: people, animals, things, big things. She had a light touch, but it was a potent one in steering the ship here towards a coherent book.

And how did your collaboration come about?

SM: I had been a longtime fan of Liana’s work. I love all minimalist work. I'd always been somebody who makes it and consumes it. And Liana’s drawings look easy because they're simple but they're deceptively complex, emotionally complex. She just sort of confronts the ineffable and gets right up against it.

Right, that abyss again.

SM: She is so intimate with the abyss, and I love the way her work just teeters on the edge and delivers this incredibly dense material in such small packages. And so I knew her sensibility just really matched the vibe that the kids had already contributed to the text. I reached out to her initially around 2021. I had recently gotten divorced, and I actually bought one of Liana’s custom redrawings of one of my favorite drawings of hers. It's a woman tiptoeing around a man's feelings. And somewhere along the back and forth about the drawing, we got to talk. I just sort of said, I love your work. And Liana knew my name and had seen some of my work before. And so we discovered we were mutual admirers. And I’m never so forward but I think I just sort of came out and asked her if she would ever want to collaborate on a book. And I had this idea. We had a couple of other ideas too, things that we might still do down the line, but I remember the first few little preliminary drawings that she sent me based on just a handful of questions that I had sent her. And she worked so fast. I mean, it was exactly as I imagined it would be. She's just fast, brilliant, so funny, so much fun. And I mean, for me, that was the best part of the project to just- I would give Liana a little bit of material and I would get so much back. And it became a coherent part of the process relatively early on. Liana’s work, the kids' work, my curatorial work, and trying to put things together and have them be coherent.

LF: This was the first thing I ever agreed to collaborate on and that was because I was really a fan of Sarah's. I couldn't remember what things I had read by her because they were all on my phone, but I knew I loved them and I had read them. And at some point, I don't remember if it was before the collaboration request or after, I started actually reading her books. And now I'm an obsessive fan, and you're one of my few absolute favorite writers. You're one of the people who's just out of my reach, which is the best kind of writer to read. I've done a lot of illustration projects, but this felt more like a collaboration request. And those I often don't do because I want to save my creative mind for my own work. This felt more like a challenge and a stretch and a broadening of my world than someone asking to borrow my brain. I also worry about collaborating because I don't really know how to work with people. And now I feel like we did work together and it was really, really fun.

I'm interested in that difference. Tell me a little bit more about collaboration as opposed to someone borrowing your brain. I love that turn of phrase.

LF: To me, work for hire is really delightful. It's when you just put your own aesthetics to the side and try to realize what someone else needs. And when I was younger, I worked for a graphic designer, and I think there's a big part of my heart that just loves to do that. I always wish I got to work in publishing and be in an office and kind of collaborate with other people on making something that my name isn't on. So that's how I think of work for hire. I would not do that for not a fixed amount of money. So I think that a lot of collaboration requests are from people where I really wish they would just hire me and then I could act like a worker, but if they call it a collaboration, then I don't do it. This felt more like a work of translation. I felt like I was channeling Sarah and channeling these children. I was kind of putting my own self aside in a very different way and trying to illuminate and magnify and get people to notice their intention. I've done a couple works of translation in the past where I translated a bunch of Yiddish advice column letters into comics. That was one and another is that I translated the book of Genesis into comics. So this felt to me like that, where it's really serious work, it feels scholarly, and there was a real balance for me between doing what Sarah wanted and questioning what Sarah wanted. When I'm working for hire, I don't question, but in this case, I just really needed- I trusted you. I trusted that everything you wanted was for a reason, but I couldn't just do it without understanding it. I really needed to understand everything, so there was conversation.

What kind of conversation?

LF: When I first saw these questions by children, my instinct as a cartoonist was to turn them on their head and draw out- make fun of them basically. And so I was drawing these funny illustrations where I was taking these pretty serious questions and kind of finding the bathos in them. And the final result is that my drawings are much more like the questions than opposing the questions. So you steered me to be an appreciator of these children's questions instead of a disruptor of them. And I really like how that turned out. But I think that result came from working with you and hearing you and understanding you. And I think the second time I read your foreword, it just completely made sense to me that these questions are about the abyss.

I'm wondering, Sarah, from your side of things, whether the collaboration made anything new possible, or something you weren't expecting in the way that Liana just described. Did Liana’s work change the way you thought of the text?

SM: Oh, hugely. There was one point very early on after I showed some preliminary list of the questions to my good friends who I usually show my work to when it's in process and the text was very dense. I hadn't yet thought maybe illustrations could help it along to become the book that I wanted it to be. I was thinking of a book, maybe two questions per page, and I was also thinking of a different version of the book that would have many, many more questions, thousands and thousands of questions, and it would just be running text pages full of questions. It was interesting. Some of my trusted readers said, ‘That's the way you should go. You should just have thousands and thousands and thousands of questions.’ And others thought, ‘I don't know, why are you even doing this? It doesn't really- it's just kid stuff. It's kids say the darnedest things.’ And both of those responses were really important in helping me along toward realizing the final form of the book. And as soon as I saw Liana’s initial sketches, it really was a moment that I knew I had made a good decision. Sometimes we take these meandering paths towards realizing the final forms of our creative work, but this was absolutely a step forward because I realized that on a page with one question rendered by Liana, with a drawing, with handwriting, each question was finally dignified. I love that Liana describes the project as a project in translation, but it is also a project in honoring the work. And it's kind of an odd thing. It's definitely a book. I feel ownership over it as a work of- it's a creative project that I made or I steered in part. But something else Liana said just in conversation about the book, it's not just a collaboration between the author and the illustrator, but we're also collaborating with all of these hundreds and hundreds of children. And so it was when the illustrations kind of came online as this coherent part of the book that I realized they hold up the text. I think books can go in various ways and they can be variously successful. This book could have been in different forms but I am confident that having thousands and thousands of questions and many questions on a page was not the way to dignify them, although I understand where that note came from. Sara, something you asked, was it just sort of like you know it when you see it? And I guess I would say like, yes, but it's our instinct. Liana and I are both decades into our creative practices. I trust my instinct. When my instinct tells me something so strongly is a step in the right direction, I obey it, and that's how it felt.

Sarah, in your introduction, you characterize these questions as “found choral philosophy,” a phrase I love. It reminded me of a definition of philosophy I once heard, which is that it is the field that tries to answer questions that come naturally only to children with tools that come naturally only to lawyers. This book made me think about our need or our desire to answer those kinds of questions and I'm wondering in what way you consider them unanswerable?

SM: Oh, this is such a great question.

LM: I second that question.

SM: Well, early on in parenting my own kid, I came to very clearly understand that there was- I mean, to repeat the words that have come up a couple of times now, there's something very dignified in the way that he was figuring out what it all was. And it was very easy to see that his questions were an interesting text all on their own. And of course in the moment I tried to answer them, but I found that even trying to answer a question as simple as, ‘What does a gargoyle say?’ Like, ‘oh, a gargoyle isn't a live animal, it's just a construction,’ all those smart, analytical things that an adult will know, but there was always some ineffable quality of his questions that remained untouched and untouchable and unanswerable. Even if I could answer a question, ‘How do sinks work?’ ‘Do you think all movies are made up?’ I mean, it’s the do you think that really dignifies that one, right? I mean, could we even ever know?

So I made the mistake of getting a humanities PhD when my older two were in this pre-literate stage, and I would be constantly over-explaining things. I was so in my own head about like, okay, ‘Well, let's start with-

SM: First, some context. What do you know about the ancient Greeks?’

Exactly. ‘So, actually, this practice comes to us from the Persians and their beliefs about the afterlife.’ And I just always struggled with, how am I supposed to- In what way is it best for you if I answer? You know what I mean?

SM: Right, age appropriate.

This is all to say that I agree with you, something remains untouchable about these very philosophical questions. And yet, they do expect us to answer them.

SM: And they think they're just pushing the button for the answer, but there's so much work that you need to do to answer them. And in the end, after answering a series of questions, because there's never just one, I thought by far the most interesting part of this conversation was the question. It wasn't my attempt to answer it with whatever knowledge about the world that I have simply by having lived on it longer. And so I called the text a choral philosophy because it seemed so clear to me that all of these three- and four-year-olds were- it's almost like they were reporting from the same sense of unknowing. They're in this realm and they're all there together. It was fantastic to see how much repetition there was in the questions that we gathered, and we gathered them in multiple languages and from different parts of the world, and all of these young, three to four, three to five-year-old people were saying the same stuff.

Right, so there’s that urge to overfill the container with response, but there's another impulse that I’ve also had, and I'm interested in whether you two have as well, where there's a kind of paralysis because it's in the answers to some of these kinds of questions that children learn their culture. And by culture I guess I mean culture very broadly and also often very specifically their parents' values or the world that they have been born into, whatever that is. A particular religion or no religion or gender norms, whatever. So at times I have felt this strong desire to not answer them because it felt like the first step in replicating some of the things I didn’t like about a given culture. They are asking because they want to know how the world works, and sometimes you want to be like, ‘I don't want to tell you how it works because I really want it to work differently for you.’

LF: The two questions that my son asked me this morning that I can remember that were hard to answer were one, ‘Will you ever go to prison?’ And two, he said, ‘Does not everyone have an aunt or aunts?’ And I explained that an aunt is when one of your parents has a sister or a sibling who's married to a woman, and then that's an aunt. And then he was like, ‘Well, what if I married you and baby sister and the dog and both of my aunts?’ or something. And then I was just like, yeah, how much do I explain? And I don't know, I'm always looking over my shoulder when I'm talking to him, very self-conscious in every realm of life. So I don't want to be the pedantic parent, and I want to answer him in a way that's delightful and preserve some of his weirdness. And I want also for him to have a really nice, broad worldview. It always feels like a performance that I'm being asked to do, and I'm always doing it a different way. And I do agree that the questions are always the real star of the show. I kind of veer between answering in a way that tries to make him think differently from other people- When he asks me about witches, I never ever say witches are bad and scary. I always say witches are people who maybe wouldn't bring something to the daycare potluck. And so people are angry at them, and when you're angry at someone, you draw them looking scary, but they didn't actually look scary. People just didn't like them, but we like them. But yeah, I think my aim is always to- so that's super pedantic, and my aim is always to fold up that pedantry into a really delightful package. And I'm not there yet, but I want the soul of the pedantry, but a more delightful way to present it to him. A friend of mine explains to her children that the very hungry caterpillar is fat, but it's okay to be fat.

I think you said you started this collaboration around 2021 and so, Liana, you either did not have a child yet, or if I'm doing the math correctly, or you were about to have one.

LF: I knew I was pregnant by February 2021. Had we spoken before then? I mean, I think you got in touch before I was pregnant. I'm not sure.

But either way, you're working on this project as a person who had yet to-

LF: Have a questioning child.

Exactly. And also in relation to your existing work, which seems very concerned with pushing on a kind of calcified worldview.

LF: Yeah, absolutely. I think a big shift for me after having a child has been shifting to being the more calcified person in the room. I think I've always been the less calcified person in the room as an adult who didn't hang out with a lot of kids and who did hang out with a lot of adults. I always feel like I work on something and then my life echoes the work, and I always want to revisit it after I have lived it. I wrote a children's book for two year olds when my son was an infant, and then I wrote a children's book for three- or four-year-olds when my son was two. And always the minute it comes out, he's already the right age, which is very nice to have a ready-made book for him. But the latest book was about feelings, and suddenly he's having these complex feelings that I had no idea what I was talking about when I wrote the book, I think, and I got some of them right, and that's good, but I want to revisit it. And these questions also, I'm now very much experiencing that. Just as we finished the book, he started asking questions, but there's something magical about that. There's a lesson about trust there that I have to trust that other people's experiences are valid and are things that I too will experience in the fullness of time.

This is not on the topic of this book, but because I have both of you here, I want to ask about Liana’s recent piece in the New York Times, “I Quit the Patriarchy and Rescued My Marriage” because it seems to me like that is another question without an answer, or at least a good one, right? Finding equity in heterosexual marriage, this is something I know Sarah's done a lot of thinking about so I guess it's the question of whether, if I was understanding it correctly, like backing away slowly from language like it's going to explode if we make any sudden movements, the decision to not name things, can be a kind of answer or solution to that lack of equity.

LF: You've got some of it. There's more. My experience that I was very diplomatic about writing about was being married to someone who's struggling with organization because of being neurodivergent and me coming from a place of being a real sword-carrying feminist and reading into his actions as coming from a patriarchal place. So backing away a little bit from the patriarchal language when it comes to working on our relationship and talking to my husband was actually very helpful in getting the same results that I wanted because his set of words and experiences were coming from a really different place, which is not to say that my feminist rage wasn't valid, only that it wasn't working in this case. And I think many women from worse times- I hate that I'm having to use tactics that Queen Esther used or something, like pre-feminist times. In my case, they work better, and I wrestle with that. I didn't say quite how much I wrestle in the piece.

Yeah that’s fascinating. A project I'm working on right now is set in premodern times, and that idea that women were not completely powerless- there were tactics but a lot of it was hidden. There was a shift to interiority, to keeping things inside, as opposed to what you call the naming of things always, and the trying to put a label on problems as a way of solving them. And I'm wondering if we are entering or have already entered a time where we're going to need to know more about those skills, which I know is not exactly what you're talking about.

LF: No, it is. I think so much about Nancy Pelosi. The meaning of what she did has changed a lot since the election but when she kind of like sweet-talked Biden into stepping down, that was fascinating. That was women's work that she did.

Right, a very traditional, soft power approach. That's really interesting. The whole idea of consciously retreating from language is fascinating and challenging to me and it’s interesting to think about it in the context of this book where you try to honor a simpler form of language and questioning. I'm wondering what you think about all this, Sarah. It's so hard for book people to feel like sometimes you have to just step away from language.

LF: And cartoons more so. They're the most punch you in the face, I think,

SM: Yeah, that's a great question because I feel instructed by it. What you've kind of inspired me to see just now is that I feel that I've kind of returned in a way to the way that I was dealing with language and literature when I was only writing poems. This was 30 years ago, but I just didn't feel that I needed to explain very much. I was sort of very easily, fully stimulated by very small texts, and I just felt that I couldn't even imagine writing a piece of literature that was more than half a page because it was so potent and there was so much that it needed to be able to say without being immediately squashed or stepped on. And it was only then really as a poet just starting out, but I really felt like every word could breathe, and I write in a different register now. I write in a register that will allow a whole page to be filled with text, and to have it be coherent and not discordant and not overly complicated. And the kind of relationship that I have with the text of Questions Without Answers feels really similar to the relationship that I had with my earliest prompts. So yeah, I'm excited to have this realization in real time as you're prompting me to think about these things.

LF: I always think of novels as being very avoidant, which is kind of the opposite of what you're saying.

SM: Well, they're indirect.

Say so much more about that, please.

LF: So the news about Alice Munro very much validated my feelings that novelists are just people who- and by novelists, I don't mean Sarah.

SM: It's okay.

LF: No, I really don't. I don't mean Rachel Cusk- well, maybe some of her books. I mean Alice Munro, I mean someone who just hallucinates this story that comes out of nowhere. I'm fascinated by it, and to me, that's very Queen Esther. Your way of coping with whatever is unsaid is to just leave your body and hallucinate this other universe. The more text, the less direct.

SM: And it's not that it's necessarily evasive, it just- if you're going to make more text and not have it be repetitious or unnecessary, then yeah, you can't just come right at the thing and say it. That was really hard for me to unlearn. Well, not unlearn, but it was really hard for me to leave aside all of the things that I learned about writing short texts as I came to be interested in writing longer texts.

LF: I think your long texts are very direct.

So, Liana, you think that people who write novels are trying to- there are things that they can't say.

LF: Yeah and it comes out like an oyster’s pearl, and I don't mean just a big book with a lot of text. I mean a very specific kind of story, and I wish I had a better way to differentiate. I think about it a lot. I think Tolstoy, very much so.

How do you think of your own work? You are more confrontational.

LF: I'm so confrontational. I think about it a lot because I always want to analytically learn how to be less so. I think it would serve me well and it would serve my art well, too, and it would serve my marriage well. And in some realms I've learned to be a little less. But yet I worry that it's made me make less art. I think in life I've gotten much less confrontational, and I am doing fewer cartoons, and I wish it meant I was doing more longer form, thoughtful pieces.

Do you think that there's a relationship between the life and the work? That’s kind of the whole thing of this Substack, how having the people impacts the work. Is it the more that that kind of bubble grows- is it edging out the art, or is it just that you feel like there are certain things you can't say anymore?

LF: It’s forcing the art to change. On the good side, I'm much less lonely and I'm much less easily triggered, so I don't need the same catharsis every second, and I don't need my art to serve that purpose. And I just want to disappear into something more elaborate and ornate. On the bad side, I don't want to offend my in-laws, so I can't write honestly about my life, so I need to be less direct. And on the cosmically bad side and cosmically good side, it's hard to shift. It's such a blessing to be pushed to shift the kind of work you make, but it's logistically hard to do so.

Order this delight of a book for all the questioners and answerers in your life ((and save money with code QA15).

Thanks so much for having us on your Substack, Sara. It was a delight to speak with you.

Could not love this interview any more. So heartfelt and lovely. . . and the illustration is amazing.