“Hormones Are For Real and I Am a Female Animal”

A Conversation with Rachel Yoder

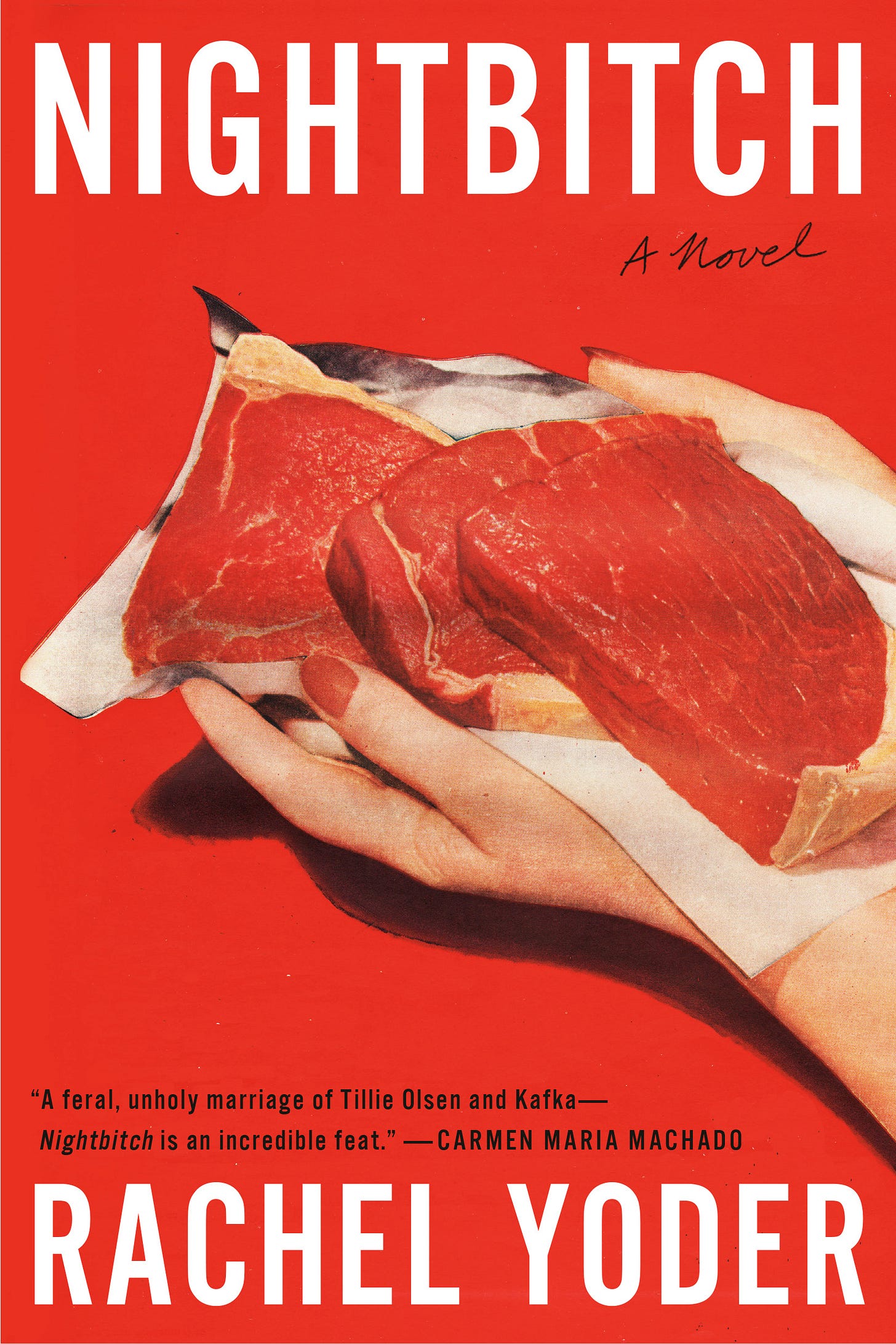

One could argue that we are in a golden age of literary motherhood. Novels and creative nonfiction on pregnancy, childbirth, and the caretaking of small children abound in a way that they didn’t when I first started having kids almost a decade ago [face screaming in fear emoji]. Some of those books – Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation, Sheila Heti’s Motherhood, Julia Fine’s The Upstairs House, and Kate Zambreno’s latest, To Write As If Already Dead, to name a few – specifically wrestle with the impact of motherhood on art-making. And into this emerging canon bounds Rachel Yoder’s Nightbitch, 2021’s most highly anticipated novel in a very specific writer-mother corner of the internet. Not that anyone was particularly worried considering it is already being developed into a movie starring Amy Adams, but I am here to report, gleefully, that the book does not disappoint.

At one point in a conversation I could have kept having forever, I asked about the decision to leave some of the book’s characters nameless. She was less concerned, Rachel explained, with realism and more interested in characters as the embodiment of ideas and in trying to figure out the story that those ideas wanted to tell. We both used the word “myth” to try and describe this impulse but as I was thinking it over a few days later, I realized that the term we were looking for was probably not mythology but parable. Parables are stories that are told not just to entertain but to teach. The characters in parables are non-specific (the wealthy father, the prodigal son, the prince, the peasant) and they exist in service of the story and its message. Nightbitch is that kind of story, meant to illustrate a problem and, perhaps, a solution.

The problem that Nightbitch poses is the problem of early motherhood. Specifically, the problem of early motherhood as the moment when you become unsure of your own identity, a time when it can feel like who you are is far less important than what you have become for another person.

This is a new kind of coming of age, a bewildering form of bildungsroman (or, a künstlerroman low on kunst) because we are used to thinking that we become ourselves earlier in life and as the result of only certain categories of experience. We have only so many kinds of narratives of self-discovery and early motherhood has never really been one of them. But seeing the sun come up with a baby who has only just fallen asleep after hours of pacing or showing your cracked and bleeding nipple to a stranger who better be able to help you or you don’t know what you’ll do or watching your partner head out to work as if life is exactly the same as it was before the two of you decided to make another human being, these are the building blocks of a new identity.

How do we step into those new selves without completely abandoning our old ones? How do we go back to making other things, dreaming our little dreams, locking ourselves in far-away rooms, doing what art-making demands of us, when we are acutely aware of just what we are to another human being? Nightbitch gives us a framework and an occasion to ask these questions and the book has its own ideas about how to answer them. Do yourself a favor and pre-order this book, and then read on for my conversation with Rachel Yoder on being an animal, developing a new literature of motherhood, and how a wizard helped her write again.

I read this book when I was six weeks postpartum so there were a lot of feelings, obviously, but both the book and my personal circumstances reminded me that the newborn stage is when I feel the most kinship with my fellow animals. The way you’re just kind of like a body carrying around another body. A few months ago, there was a chimp born in the zoo here and there were all these videos on Instagram of the mother and baby and I was like, oh yeah, that’s going to be me soon because it all looked so familiar, the carrying and the nursing and the inspecting of the head while you're nursing. So I guess my question is: was it always a dog? Did the dog come first or was it just “animal” and then you got more specific later?

I had not slept in a number of years. I was the primary caregiver for our son. I was incredibly sleep-deprived and I still felt like an animal two years out simply because of the stress being put on my physical body. I started getting very angry in the night if anything woke me up because I was in survival mode still and one morning he made this joke, “you were sort of like a bitch last night when you woke up. You know, like nightbitch?” And it was just a joke that gave me pause. I hadn't written for two years. My son was born and then I just stopped writing and that was this other stressor on my psyche. And for some reason Nightbitch was absurd enough and funny enough and it just felt like a playful literary problem I could explore. And that's what I needed to get into the book. And I didn't really interrogate it all that much because I didn't even know I was writing a book. I just thought, oh, this is a way in to writing about all these things that I need to write about that I haven’t written about for two years, which is a longwinded way of saying, it’s almost like saying that it's a dog is almost too simple because it's just that primal, animal part of her, which I guess comes out. We have to call it something, right? And the werewolf is sort of a known entity.

I'm obsessed with talking to other writers about process and particularly women and particularly mothers so I do want to ask you the very logistical questions, like how long it took, what your childcare situation was like.

My story is very similar to Nightbitch’s in a lot of ways. I got a sort of dream job directing a literary nonprofit and my husband, meanwhile, got a job where he was gone every week. I always thought I would be parenting with my husband and it would be very progressive and modern and there wouldn't be traditional roles we were fulfilling and we would share equal responsibilities. And that wasn't how it was at all. When I decided to quit my job and stay home, there wasn't any money for childcare because we were down to one career. So it was like, okay, well you can just write while the baby sleeps. I mean, no that didn't work, I was exhausted myself. I was just getting by, just surviving.

And also you don't know how long that baby's going to sleep! It's not like they give you a memo of, ‘I'm going to sleep for 20 minutes this time, 45 minutes next time.’ It's absurd. The whole sleep when the baby sleeps, or do anything while the baby sleeps, is one of my biggest pet peeves.

It's ridiculous. And it's also not like the creative process is like, you clock in and clock out, you punch your card, right? You have to dream yourself back into your project. So I just sort of gritted my teeth. I felt very lucky to be able to quit my job and be home with my child, but then it came with all these huge trade-offs: that I love to work, that I had gotten two MFAs and spent 20 years dedicating myself to writing and now was not writing and on and on and on. So I didn't write for two years and it was a really big problem. I mean, I think it was a huge piece of why I sort of had a mental breakdown because I totally lost myself. And it just happened to coincide with when all of my graduate school friends were moving away. All of my friends had moved away, I wasn't writing, I was alone in the house with a child five days a week. The other piece of of it was that because we were alone all the time, my son was obsessed with me and did not want me out of his sight. We had this very close bond so when I did try to leave him with anyone, he would sob like I was dying, you know? And it was just- I couldn't leave him. So eventually we found this like little daycare in our neighborhood and it was a hippie daycare in a house and they're really accommodating to people who don't have the financial means to send their kids to daycare. And I went there and talked to the guy who runs it, his name's Tim and he looks like a wizard, he has a long white beard. And I was like, I'm an artist and I need to write a book and I just need like three hours a day. And he was like, yeah, we can totally do that. So somehow that worked. And it was still hard to leave my son there every day but that's how I started writing again.

So the wizard helped you write your book.

The wizard helped me, yes. My husband and I both knew I needed to do this for my sanity, I needed to do this for our marriage. Everything was sort of falling apart and we both knew that I needed to take some time for myself. So it started out that way and we just kind of made it work and pieced it together and it just came back. I started writing again on the weekends. When my husband was here, I would leave for three hours and go to the coffee shop. And that was my entire writing practice.

So you wrote this book three hours at a time.

Yes, absolutely.

For how long?

Well it was in fits and starts. One summer I did Jami Attenberg’s 1000 Words of Summer. I just needed something arbitrary to keep me on task so I did that one summer, then I didn't write for a couple months. And then I was like, okay I'm going to do it again in the winter so I kind of did it on my own again. My writing practice was totally transformed because before I had my son, I wrote every day, spent a lot of time meandering around in my writing. But now I plan ahead, I kind of hone ideas before I put anything to paper. I don't want to waste time and it just has to be a lot more efficient now, whatever that means. The creative process has to be a lot more efficient. But yeah, I wrote it two and three hours at a time, absolutely, a thousand words at a time.

I know that that's often how it happens but I always find it amazing to hold a book in my hands that was written that way.

I feel like we have so many things to talk about but I'm wondering if you’ve also had this experience since you have four kids, that there's also something that happened to my imaginative space after I had a child, wherein there just wasn't as much going on in there. At least right after he was born, for the first time in my life, I'm like, I don't have anything to write, there's nothing inside me that needs to come out and that is what really terrified me. I guess I haven't really thought about or interrogated that too much but I wonder, you and other mothers and writers what their experience is with the relationship between having kids and what happens to your imaginative space, your imaginative bandwidth.

That’s definitely part of the project here and it's been so interesting to see that everybody is different. For me, having a kid unlocked something and I found that I had stuff I urgently needed to write about. But that first experience of being completely responsible for another human being and being sleep deprived for sure does a number on your imaginative faculty. That whole needing to be a body thing. And it seems to me that there is this dichotomy for The Mother between her body and her mind. There are these really terrific passages where she just kind of gives in to her animal-ness and what her body wants to do, and that's when she finds joy in playing with her son. But it's also during those times, at least in the beginning, that she puts the idea of making art aside. And so the implication is that when she allows herself to be just a body, that’s when she can experience joy in motherhood. I guess what I’m saying is that I just started having childcare again and I’m a little bit sad because I feel like I’m supposed to be a body with this baby right now but I also want and need to be a mind in front of my computer.

The way that Nightbitch fully self-actualizes and turns into a god, becoming master of both motherhood and art, is by unifying the body and the mind, not turning away from the body and by getting back in touch with her body and not thinking of it as separate from the mind. That has been a journey I’ve inadvertently been on. When you become a mother, you can't look away from your body anymore. You're so embodied when you're pregnant and when you have the baby. And for someone who has learned to ignore what your body is telling you, and I think women maybe learn that more than men- that’s kind of a sweeping generalization. I didn’t know I was working with these ideas but now it’s become very apparent to me that the embodiment that motherhood foists on you whether you want it or not can be a really powerful message. And Nightbitch’s journey is really about learning how to become this full, embodied person that the different parts of herself aren’t alienated from one another. And that can be a wonderful gift of motherhood.

Something that I struggle with, and I'm ashamed that I struggle with it, is the idea of making art out of motherhood, the fear that all I'll be able to write about is parenting. And then kind of nestled in there is the implication that that's a lesser form of art, which it definitely isn't, but I think that there’s a reflexive shame or a worry that it's another version of the momfluencer, wherein women are home with their kids and they think, hey, I'm creative and I want to do something so I'm going to use the pieces of my life to create something for myself.

Yeah for sure and, if anything, I wanted to not write a book about motherhood. That was the last thing I wanted to write about because of that shame or thinking it’s not important enough or it’s just for women, which is all ridiculous but there are these messages that we've received. I think this is what women are doing right now is we're trying to find a new language for motherhood, a new literature of motherhood. And I think where that shame comes from is these old scripts that we've been given that make motherhood seem like, you know, nice and

pastel and cute and not that hard. All of that bullshit is what we don't want to write. And so my approach to that is, okay, I'm going to write the craziest fucking book you've ever seen about a mom who shits on her neighbor's yard. I'm just going to go all the way in the other direction as far as I can and see what happens. And I've written other nonfiction or essayistic pieces where I absolutely refuse those old narratives of motherhood. Motherhood is weird, complicated, uncomfortable, mystical and that’s what I want my writing to reflect. And I think we're working to make motherhood what it should be which is this viable, incredibly important, deeply valuable topic that should be up there with the literature of war. There's nothing more interesting than writing about motherhood, I don't think. And it's been relegated to this lower echelon because of patriarchy and sexism and all of these forces that have been working against us for centuries. And it does seem like we're sort of at this tipping point where there's a lot of women who are, like, nope, we’re here to challenge all of that and we're here to claim our rightful place in the culture, our rightful importance in the culture, and that's exciting to me. And I'm interested to see where that goes.

I’m thinking about what you said because I also went into this expecting an equal partnership and a balance and all that. And I do have a really great partner and it wasn’t that he dropped the ball, it was that my relationship to our child in the beginning was just so unavoidably physical and chemical, we were intertwined. And there were things that he couldn't do and things that I didn't want him to do. And that was by choice. I struggle with it because patriarchy is definitely involved but there were things that I wanted to do, that felt right. And this is where I so appreciate this book because those things felt right to me in my body but it still caused all sorts of problems. Does that make sense?

Yeah, oh for sure. I think it's really hard these days to talk about the realities of biology that became very apparent to me after I had a child. Hormones are for real and I am a female animal and there are certain things that I want that my male partner simply does not. He’s very different from me in a lot of fundamental ways biologically and that seems kind of scary to say. But it's so apparent when you have a child and then also raising a child and seeing the way he is his own person apart from anything that I want him to be. And there are realities of his biology that are uncontrollable. We were like, we’re going to only have non-gendered toys and he never touched a stuffed animal and only wanted things with wheels. And we're like, oh, okay. How do you fold that into your progressive comprehension and philosophy of the world? Biology kind of complicated that for me, becoming a mother.

I know that you come from a religious community, you grew up Mennonite. I'm an Orthodox Jew and I think that it's particularly hard because I consider myself a pretty progressive person and I struggle with the patriarchy of religion in a very big way. To then have to kind of concede part of that, to say that there is that difference, is very tricky. The way you describe Nightbitch’s journey is often inflected with the language of religion. Do you feel that that life and that language constrains you at all anymore or do you feel that you can draw on it when it’s fruitful and discard it when it’s not?

What a great question. That's totally been on my mind lately because, as I'm moving into midlife, I am returning to the language and images and metaphors of religion and understanding them in a way I never did. They are taking on deeper meaning for me and I think that's okay. It doesn't mean I'm going back to the church because I think the church is something that's very different than its stories and its images. And I am interested in ecstasy and in a path to God, and probably not God as how the church conceives of God. But that's something that I'm working with right now. That language is still resonant with me and I think the book was just the beginning of this, but I'm figuring out how to integrate that into my understanding of myself and my family and the world. I find those images and that language actually incredibly helpful and beautiful. My editor challenged the word miracle in the final sentence of the book. She's like, I don't think you want that word and I'm like, no, I absolutely want that word because I think the book is about integrating what was once rejected, integrating the spiritual and finding a place for it in your life as a secular person because I do think there's a place for it. And I think that one thing that our culture is really lacking is any sort of spiritual education or tools or a language to give to ourselves and give to our children for talking about this very human experience, this sense that we come in touch with at parts of our lives that there's something bigger, that there's something we're a part of. We don't quite know how to talk about it outside of religion. And so I think that the book was kind of making those first gestures toward this sort of exploration. I don't think it's as easy as rejecting the religion of my childhood. It's like, how can that still be a value to me?

Yeah, which parts do you take with you and which do you leave behind. I want to ask you about how you refer to the character. She's always either “the mother” or “Nightbitch.” And “the husband,” “the boy,” neither of them have names. Sometimes people on the internet get upset about characters not having names. The wan little husks of it all.

My earliest and most simplistic thinking was it didn’t feel right to give them names. It felt too specific. I guess I was thinking more of the characters as ideas that I was sort of animating and putting into play and into relationship in the story. Nightbitch – the most important character details about her are that she's a mother and a wife and an artist. I just really saw it in more of a mythic way. I was more interested in the story as a myth than I was in it as some realistic reproduction. And I know some people already have sort of blanched at that idea but that was just my approach. I probably shouldn’t say this but I’m not much interested in realism in general. I’m more interested in the archetypes that we’re all working with, even though I realize that this story isn't going to ring true for everyone, that there is a socio-economic context, there is a race context. And certainly those people will have stuff to say about those and I would love to hear their thoughts but my focus was really on the characters as embodiment of archetypes, as embodiment of ideas, and trying to figure out the story that those ideas tell.

Yeah it felt almost like religious mythology to me, like an etiology. Because that's what religion does, it takes universal human feelings – you know, someone died and I'm sad, someone is born and I'm happy – and offers us stories and rituals for them. And this reads to me like another very necessary story about motherhood. I was struck by the fact that Nightbitch’s relationship with her husband and her relationships with other moms evolve from the beginning of the book to the end. Your relationship to your partner changes when you have a child and your relationship to other women also changes, or has the potential to change. And there’s all this new potential in both of those cases for opposition or antagonism instead of solidarity for a whole bunch of reasons. What was your thinking on that front? Because it's easy to have that oppositional relationship where the dad isn't doing enough or to pit women against each other.

Yeah, and I think that was a real big question for me in my own life. I was really baffled by how to find that kinship and solidarity with others. And I think it's still a journey that I'm on because I am sort of a loner and an introvert. And I was writing this book out of a lot of loneliness. I felt so isolated and so incapable of figuring out how to not be isolated in early motherhood. It was just absolutely baffling to me. And that was also a kind of a baffling question for the plot or narrative of the book. How do I get these characters to solidarity, to working together, to a point of understanding? Because I think that's truly what Nightbitch wanted. And it is so easy to be alienated from your partner and alienated from other moms, even from other women. So really, how do you do that? How do you get closer to the natural allies in your life? How do you figure that out if you're a person who is used to being independent and being self-sufficient and having dreams and having a direction all on your own? How do you come into community? And that seems like a question that's really present for a lot of people, especially after a pandemic. And especially outside of religion, because the wonderful thing about religion is that you go see the same people once a week, you have this building community, you have this way of being together. It’s a compelling question, I think.

Nightbitch publishes on 7/20 - preorder your copy here.

I loved Nightbitch and I love the idea of creating a literature of motherhood. Thanks for this interview!

"And so the implication is that when she allows herself to be just a body, that’s when she can experience joy in motherhood. I guess what I’m saying is that I just started having childcare again and I’m a little bit sad because I feel like I’m supposed to be a body with this baby right now but I also want and need to be a mind in front of my computer."

I am SO in the middle of this contrast right now (7 mo old ebf baby / spotty childcare / trying to edit a poetry manuscript), thank you for spelling it out so clearly! Really enjoyed this and really happy to have found your newsletter, thank you for your work!