"I Did It by Giving Up"

A Conversation with Steve Almond

It’s old news by now but I’m still thinking about The Cut’s age gap essay. Of course, as many, many (so many) people have pointed out, it’s more of a wealth gap essay than an age gap essay. And yes, it traffics in Tradwifery tropes of how good it feels to lay down your Votes for Women placard and just accept the loving support of your (hopefully wealthy) husband. The relief of not trying so hard anymore.

But it’s also an essay about writing; about wanting to write and trying to hack the impossible economics of this cursed trade.

Ambitious, hungry, he needed someone smart enough to sustain his interest, but flexible enough in her habits to build them around his hours. I could. I do: read myself occupied, make myself free, materialize beside him when he calls for me. In exchange, I left a lucrative but deadening spreadsheet job to write full-time, without having to live like a writer. I learned to cook, a little, and decorate, somewhat poorly. Mostly I get to read, to walk central London and Miami and think in delicious circles, to work hard, when necessary, for free, and write stories for far less than minimum wage when I tally all the hours I take to write them.

On the one hand, who among us hasn’t fantasized about being able to write without the pressures of having to earn a living and/or care for the kinds of people who don’t allow for delicious circle-thinking? If you read this Substack, it’s likely you are trying to do many things at once and I think we can all agree that it’s exhausting.

This young woman sees what we’re trying to do and she reminds us that “There is no brand of feminism which achieved female rest” (was that the goal?). She also sees our children: “Very soon, we will decide to have children, and I don’t panic over last gasps of fun, because I took so many big breaths of it early…If such a thing as maternal energy exists, mine was never depleted.”

I thought like this at 27 too, that I would get all of that living – all of that napping and travel and needing – out of the way before I had kids. But you can’t really rest in advance for what kids will do to your sleep or your spirit, and there is no hack for being a person, particularly a woman, with needs and desires and ambition. That last word is kind of the key term because an ambitious person doesn't just get their ambition out of the way and a person who wants to write will always have more things she wants to write, sometimes most desperately after she has a child and experiences that constriction of time with which so many of us are familiar.

The essay is part of a series called “The Good Life,” which bills itself as “a series about ways to take life off ‘hard mode’” and therein lies both the rub and the connection to this month’s interlocutor. I’ve learned a lot about writing from Steve Almond but foremost among those lessons is this: there is no cheat code for doing this work. Writing is not ease and it is not restful. It is endless excavation and relentless decision-making. Will this essayist outsource that to her husband as well?

I’m inside a new project right now and that project has me reading Petrarch, who also had ideas about age gap relationships. When evaluating a prospective wife, he recommends that men choose someone young and virginal:

For a noble maiden, devoted to you from an early age and distanced from her people’s flatteries and old women’s gossipings, will be more chaste and humble, more obedient and holy…once she joins you in the nuptial bed, hearing, seeing, and thinking of you alone, she will be transformed into your image alone and will adopt your ways.

Consider the synergy:

Mostly I worry that if he ever betrayed me and I had to move on, I would survive, but would find in my humor, preferences, the way I make coffee or the bed nothing that he did not teach, change, mold, recompose, stamp with his initials, the way Renaissance painters hid in their paintings their faces among a crowd.

How telling that the metaphor turns her husband into the artist.

Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe this is the way and the rest of us are just jealous naysayers, bitter crones who have given too much of ourselves from too young an age. Maybe this writer will make a great success of her strategic delegation of income generation and taste-making, and some day teachers of creative writing will distribute copies of this essay to college students they think could make a go of a writing career.

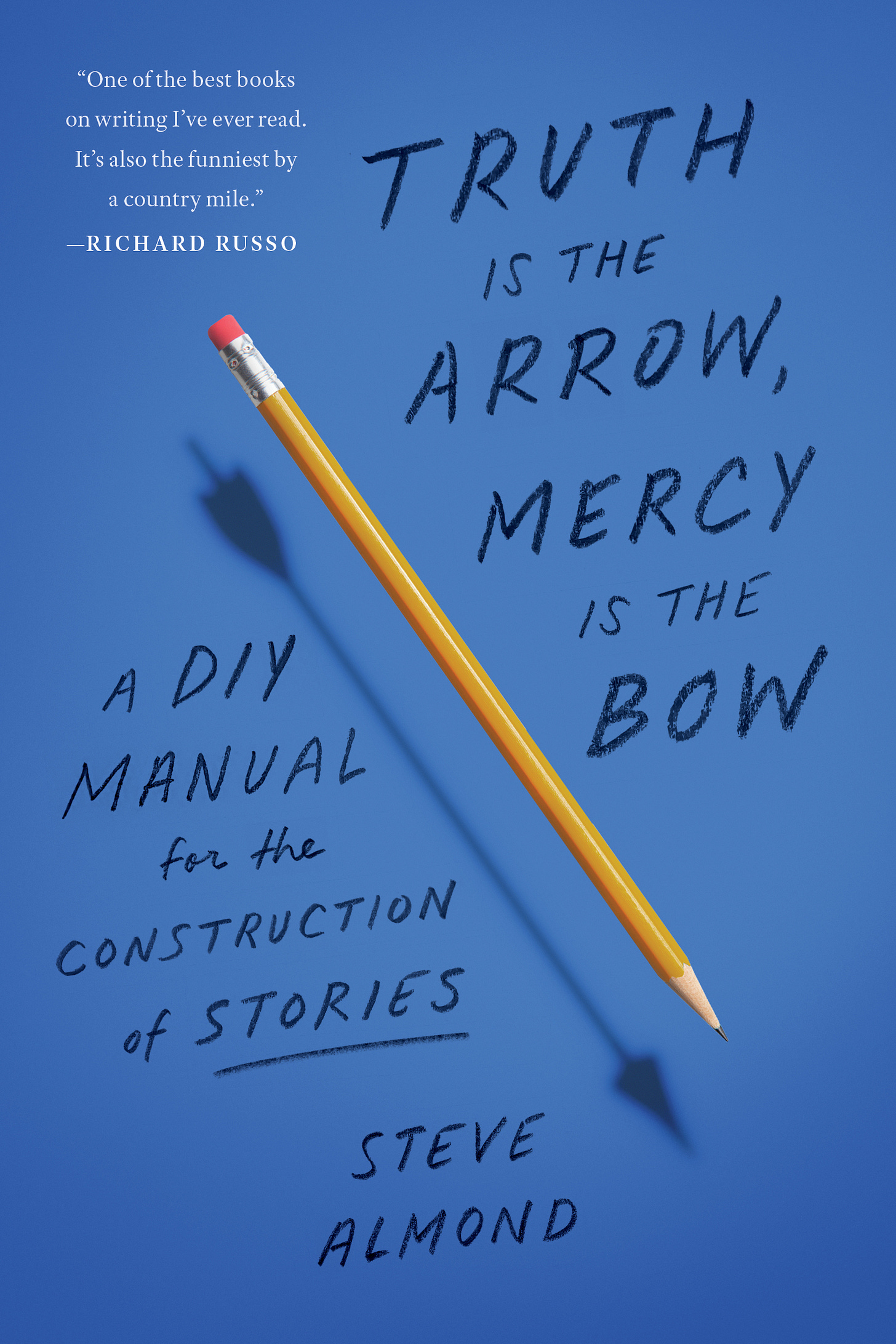

But if not, if it turns out that writing does require a tolerance for both decision-making and unease, the good news is that this writer already has the voice-y opening to the novel she may someday want to write about a character convinced she’s hacked the problems of being a woman and an artist and is is about to learn some lessons. If you’re reading this, future Grazie Sophia Christie, grab yourself a copy of Steve Almond’s craft book, Truth is the Arrow, Mercy is the Bow: A DIY Manual for the Construction of Stories, published back in those delicious circle-thinking days of April 2024. It is full of wisdom, including the idea that the best writing comes out of searching rather than certainty; an agonizing final truth instead of a smug, knowing conclusion. “We always turn away from unbearable feeling,” Steve writes in his banger of a final chapter. “We want to feel sure of ourselves. We want to skip the part of the story where the hero falls apart. It’s an instinct. But that’s the story the reader wants to hear, the one only another human being in pain can tell them.”

Read on for my conversation with Steve about the authority of failure, uncoupling artistic creation from financial expectation, and why you don’t have to worry about whether or not you can call yourself a writer.

You’ve written a great many books and you teach; you had a very popular podcast for a while. I also learned from this book that your wife is a writer. And you have three children. All of that together seems like a high level of difficulty. Can you talk to me about your career arc alongside your parenting arc?

It’s a lot and both Erin and I feel the stress of it a lot. There is no solution to it. There is recognizing that it's hard to have a creative life and it's hard to figure out how to support yourself if you're not on the great capitalist grid. And if you don't have a side hustle or a really wealthy family or an inheritance or whatever, you're going to have to figure out how to balance a lot of stuff and how to accept that it's going to be out of balance a lot. And I think over the years we've really worked on that. When the home has become so stressful that it's impossible to do creative work, we realize like, okay, we need to be able to go away to do these larger projects. We have to go away and the other partner has to grant us that grace and they have to know they're going to have their turn. And we also have to accept, okay, we've got strengths and different roles. I am not, as this interview and any interview I ever have, or any human interaction I ever have will indicate, a supremely organized person. I have disordered thinking – enthusiastic but disordered. And so I am not the person to organize the weekly schedule most effectively. Erin’s better at that, but there are certain things that I am good at and certain things that are less onerous for me. And so you kind of have to figure out what you're better at and what you hate less. Try to take those things off your partner's plate and then admit the things that you're not as good at and seek permission to take them off your plate.

Has it been helpful that you were already an established writer once you had kids? Did it make it easier to ask for that time away?

It's not very profitable and I think we've had to have a different kind of math than people who are traditionally employed. It's not the same thing to say, I'm a novelist and here's the profit I generate and here's what I'm going to make in the third quarter of 2000.

Right, but even setting aside profit, you can work on something for many years and it doesn't end up getting to readers. You’ve had a bunch of books that never saw the light of day.

That's part of an apprenticeship and it doesn't get talked about a lot. And people instead get very discouraged and the people around them are saying, ‘Hey, hey, hey, you're writing. Where's the book?’ They have to understand it doesn't work like that. It’s hard enough to sit and write and make those decisions, then it's hard enough to look at those decisions and revise them and try to make them better and stronger and push your characters into more danger and clean up the chronology and the narrative stance and all the craft elements. It's just really hard to do and it's time consuming and it's choked with doubt and it is hard enough for you in the world of your characters to just listen to their voices and hear what they're struggling with. If the market or a partner or a family member is also saying to you, ‘you need to churn a profit here,’ or ‘why is this taking so long?’ it's just going to make it that much more difficult for you to focus on the characters and their struggles. So you have to somehow tell yourself a more useful story, which is ‘I'm trying to uncouple artistic creation from financial expectation and that's my job. I'm trying to learn how to write a novel or learn how to write a book or make a set of decisions and just figure out how to get stronger as a writer, have that critical faculty develop. That's what I'm at work on.’ Everybody's got a different arc. Not everybody's Mozart, not everybody’s Tolstoy. And in the world we live in, with kids and the frantic pace of culture and technology and the diminishing audience of readers for an inconvenient art form – beautiful, blessed, incandescent but inconvenient – it's a different math and everybody needs to calm down and recognize it's a different fucking math now. And to give yourself the time and space to say, I am engaged in trying to figure out how to do something difficult and I need to bring it into harmony with the rest of my life. I want to be present at the keyboard, but I also need to be present in my partnership and for being a parent, and sometimes I'm going to screw that stuff up. My job is not to publish a bestselling novel. My job is not to be the best mom or dad or partner in the world. My job is to recognize what I'm doing and esteem it and not for the sake of being negligent about places where I'm falling down on the job, but just to recognize it's a hard set of jobs that I'm trying to perform all at once.

Do you feel like you’ve been able to do that? To have that perspective?

I mean, no, that's the goal. It's like all those failed novels that you're talking about or those novels that were unpublished, the goal was to be effectively balancing that creative endeavor with what was happening in my family. And the truth is a lot of the novels and stories and essays and whatever else I've worked on, there's a giant iceberg where nine-tenths of it below the surface isn't published. And the little bit that you see and a few other people see is the published work. Same thing in my family life and partnership. Jesus, if I screwed up in lots of different ways, that is not actually inconsistent with esteeming what I was trying to do. Everybody's like ducks paddling away and it's really helpful to say: how hard is the stream coming against me and how much progress is it possible for me to make? And also to say, boy, am I paddling hard without it being an ego trip or an excuse or anything. You don't need an excuse. It's really hard to be human and it's hard to do these three things well or even to avoid doing them badly: writing something long and complicated, being a parent who's present and loving and concerned, but not controlling and anxious – which I failed at miserably many times – and being a partner who's present person.

That’s a great segue to your new book. It strikes me that you wrote it not out of a place of triumphalism but out of mostly failing to write a novel before you finally did it successfully. Can you talk to me a little bit about the authority of having failed?

I like that, the authority of having failed. That's such a great term. I'm going to just steal that and pretend that I came up with it just so we're all clear on the theft and now we have some witnesses.

It’s all yours, you can have it. I love getting words out into the world.

I'm glad you're subcontracting. But I like that because we think of failure as the ultimate loss of authority and it's such a mis-framing of it. Edison said this great thing about ‘I didn't fail a thousand times. I just learned a thousand ways to not invent the light bulb.’ It's such a revolutionary thought. That's the authority of failure. I now know that doesn't work and I don't recommend writing a bunch of novels that don't pan out. But I also now, and again with some years and having humility beat into me by my various unsuccessful endeavors and screw ups, I kind of look back and go, okay, I wish I hadn't worked on that novel for so long, it wasn't going anywhere, but I kind of had to where it was something that was too ambitious for me to take on. Maybe I'll be able to figure it out a few years from now if it calls out to me, if the muse says that piece still has energy but maybe also it was an important part of the process. My wife published a novel several years ago. She also wrote a really good novel during the pandemic that didn't get published, and I think it was great and I think she learned a lot from it. And I think there are real particular reasons that made it commercially not viable. And I also think that the whole time that she was working on that book, like the times that I've been working on my books that don't pan out, she was working her ass off, paddling away. And she knows this and I know this, you can be working really hard and if you uncouple that process from the result, you'll be a lot saner about it.

I want to talk about the hold that writing a novel has on writers. You were very successful, you had published widely and you still felt like a failure because you couldn’t make it in this one genre. Why do you think that’s so many people’s white whale?

Well, it’s great, right? Even the symbol you use to describe it is like Melville's great novel. And he writes it and then he thinks it's going to be a bestseller and he'll rise to prominence and it sinks like a stone and only history, the ultimate critic, says now that's his work of genius.

Right, and the concept of the “white whale’ itself is in our cultural lexicon because of a novel…

I don't know why for everybody else, but for me, I think it's a combination of insecure male thinking that size matters and that the way that I'll prove that I'm a real writer is only in the novel form, having my parents be really devout readers of Dickens and Austin and that model of like, oh, that's how you get mommy and daddy's attention is write a novel. Don't just write those little short stories, that's apprentice work. And I think those things colliding with what the market says, which is, short stories are nice, but they're kind of an apprentice form. Non-fiction's great, but you couldn't imagine a whole world? The voices in my head are saying that the novel is the ultimate form and there are very real reasons for that. I got closer to and more invested in Lorena Saenz’s fate than I have with other characters, and the world around her that I was able to construct was so rich and the symbols I was able to use. And it is working on a bigger canvas. I'm a short story writer natively just because of my own ADHD but it was not just some hang-up, it was also a big creative challenge that I wanted to have the pleasure of being engaged in successfully. And when I was, that was very rewarding. It got the monkey off my back. I don't know that I'll be able to figure out how to do that again, but I did it once and, weirdly, I did it by giving up. I did it by saying maybe I'll never do it. Fine, who cares? So it's an irony because the more pressure you put on yourself around something, the worse it's going to be, whether it's a creative project or a sexual encounter. Whatever it is, too much pressure leads to performance anxiety.

Was it a different creative feeling or a higher level of creative pleasure, writing the novel versus your nonfiction books?

I think there's a feeling of having sustained- I'm thinking about your novel and trying to stay with these two characters, these young lovers and tracking them through all of their convulsions and ambivalences and connections and broken connections and their intergenerational trauma and everything you were trying to track there, there's something really beautiful and amazing in a world that's so frantic and results-oriented and inattentive and splintered, to be able to hold that and to be able to hold a reader in that. I think that's amazing. And I think it's a particular kind of accomplishment and pleasure that doesn't cancel out and it doesn't really compare to the feeling of writing a short story that is delivering such an emotional jolt in such a short space or a poem or an essay that very effectively kind of travels into the inner life. I think the idea of comparing one kind of pleasure to another doesn't really make sense. I'm proud whenever I'm more interested in the story than how I'm telling it. That's when I know I'm succeeding at the keyboard.

I would read an entire book about how you wrote each of your books, their individual roads to publication. I loved your description of writing Candy Freak and the agent who said that he didn't know where it would be shelved in Borders, which, as you note, is more funny now than it was at the time. But in addition to being funny, it's instructive, which is why I assume you included it in a craft book. The idea that writing has to be this weird mix of talent and tenacity, but also you're at the mercy of trends and whatever the dominant mode of commerce is at the time. When most books were being sold at Borders, you had to be at the mercy of however Borders decided to organize their books. And so I think that story was really interesting because it shows that you've outlasted some form of gatekeeping, and also it does seem to me that the kind of hybridity, that Candy Freak exemplifies has become more common.

Yeah, I think that's probably true.

I don't know, maybe you single handedly made that happen. It's possible. I don't want to rule it out.

Yeah, like I say, you can't control much in the world, so anybody who wants to give me credit for anything, I'll take it. But I think that the simple way to say it is the reader just wants a good fucking story. The reader wants to figure out who they care about and what that person cares about, and off we go. And if that person is an erotic Jewish depressed guy in his mid-thirties who's trying to figure out what happened to the Caravelle and trying to get into chocolate factories to alleviate his depression and simultaneously weirdly return to the sorrow of his childhood and candy as the one dependable pleasure, well then, okay, that's the journey. But the writer's job is to figure out what they're most interested in, not what the market mode of commerce, blah, blah, blah, and to have faith in it. And what's instructive about the Candy Freak story is that I thought it was a silly piece of pop ephemera once those agents said they weren't interested. I put it in a drawer and it took friends of mine saying, ‘what's going on? Weren't you visiting the Goo Goo cluster and the Twin Bing factory and the Idaho Spud factory in Boise, Idaho? What happened to that book?’ And I said, ‘Oh, it was dumb. The agents didn't like it.’ And them asking ‘Can we see it?’ And reading it and not saying, ‘Oh my God, this is great’ But saying ‘This is weird and super interesting and stay at work on this. There's something here.’ That's the part of the story I think that's important is we're oftentimes terrible judges of our own work, or at least our insecurity and the bad stories we're telling ourselves and how easily discouraged we can be by an agent or an editor or a manuscript consultant. So I think it's something about how fragile the writing process is and how easily amid a set of other duties like being a partner and a parent where you're feeling a lot of failure, frankly, a lot of places where you fall short or you're frustrated with your kids or your partner, and that impatience is its own form of falling short. I think that it's easy then to get knocked off balance creatively, and, as you see from the book, I’ve tried to make my peace with, okay, failure is a part of it. It's in fact a form of authority. And not only that, but writer's block is okay, that's a teacher and it's okay to be blocked. And all these places where I could beat myself up for failing or not succeeding are actually places where I need some forgiveness and grace for myself and some patience to outlast all the doubt and all the evil voices.

A solid endorsement of both friendship and patience.

And sort of getting out of your own head and saying, you have pretty screwed up views of yourself at the moment, why don't you ask somebody who's really kind and gets who you are and what you're up to what they think?

One of the themes of the book, it seems to me, is encouraging writers to let go emotionally speaking, which I love. You write about how Barry Hannah's stories helped you come out of the closet as an emotionalist and how most people come to writing as a way to process difficult feelings, shall we say. And you argue for the role of uncontainable emotion, that those are your words in the writing process and in crafting character. I feel like that's a kind of counter-cultural position right now. And this may be changing, but it seems like the trends are more toward spare pros and a lot of containment of not letting it get out of control, so to speak. You also talk about writing sex, which I think is on that same spectrum of-

Uncontainable, right?

Yes, writing things that just seem like a lot.

Seem a lot, seem unrelatable, seem like somebody's going to object or not buy or put it into a little, do not go near caution tape. I was thinking about the Mrs. Bridge and Mr. Bridge novels as you were talking about things that are spare and contained. I think there's a difference between the mode of expression and the content of emotion. You can have a book like Mrs Bridge or Stoner, where there's absolutely unbelievable emotional valence, but its mode of expression is suppressed to the point of asphyxiation. Ishiguro, Remains of the Day devastating Uncontainable emotion doesn't mean that the character is running down the street howling like Ginsburg naked with their hair on fire. Uncontainable emotion can mean the butler Stevens holding his book and having Mrs. Kenton look at it and tease him because it's a romance and how much he burns at that; burns with desire, burns with shame, burns with his inability to separate those two emotions. Absolutely uncontainable what the story delivers. And in fact, sometimes the containment within the mode of expression in the book is actually putting the feeling onto the reader. So I guess I just want to say that when I'm writing about uncontainable emotion, I mean the inner lives of the characters, not how they're choosing to express it. And I think people can get twisted on that. They can get confused. Oh, Almond's the guy who's saying, let it all hang out. I'm saying, no, the inner life is volatile and your job is to probe into the parts of the inner life where there's that uncontainable emotion, how people choose to try to contain it or mask it is a lot of the story.

I always love when the personal comes through and you tell personal stories in this book and in your other books. Do you have rules about what you will write when it comes to the people in your life?

I think you develop more of a capacity over the course of your writing life to believe that you're going in search of mercy and forgiveness and grace and all that stuff. You're not out for revenge, you're not just power hungry. And at the same time, you have to go home for Thanksgiving and you can't feel uncomfortable in your own house. So I do know that I won't write certain things about my kids because it's not my decision to make, and it could affect them badly. And same thing with my partner, and that's probably true of my brothers and my immediate family, my friends. But I think the way that I mostly deal with it is that I'm sort of the central idiot in most of my stories. Not a lot of stories that are like, I did it right and boy, screw the other person. It's more like, fucked up again, and that's probably a more accurate take on things. And it's also just, I can live with it. The focus is on me and my foibles not on casting aspersions elsewhere. So that's sort of how I deal. No rules. And I think it's important for people to realize everybody has their own rules because everybody has been encoded with and had to absorb their own particular codes of silence through family and community. If you're a person of color or a disabled person narrative, or there's all of these voices that are saying, shut up, your story's inconvenient, your story's disruptive or destructive or threatening to our privilege, or whatever it is. So the section of the book that's really about speaking truthfully and telling unbearable stories is very much aimed at people not like me who are white guys with a lot of privilege. It's sort of: think about all the people who are trying to get you to shut up. That's the reason you shouldn't shut up.

You’ve been traditionally published a number of times but you’ve also self-published. What motivated you to self-publish certain books? What is the story of that?

What is the story of that? The story is that I had just come from the experience of publishing with Random House at the highest levels. They were going to try to call me up from double A and they believed they could somehow make me a more prominent writer. And I had my doubts about that, which were proved out. I had the authority of failure behind me. But I think in reaction to going up to the 45th floor of a skyscraper in Manhattan in midtown, which was always the fantasy of like, oh my God, all the bad parents of New York, I'll finally get on their radar and be the beloved son. And realizing that that was a false dream – there are limits to my talents and my appeal in the world that make that a false dream and a certain disillusionment – I went back to, hold on, I just want to write the shit I want to write, and I want it to be weird and idiosyncratic and anarchic, and I don't want it to follow any rules, and I don't want to worry about any numbers that I'm going to hit. And the means of production have become democratized to the point that I can literally have a book made in five minutes. As long as you have cover art and the words that you want, and you consider them carefully, that's your book. And that was revolutionary for me. It's part of the reason that I think the subtitle of the book, is A DIY Kit for the Construction of Stories. For me, the little forerunner to this craft book or book about the creative process was, This Won't Take But A Minute, Honey, which was my little craft book. So, talk about uncontainable emotion, but I remember having this vision for this book and sitting with the editor at Random House explaining it's going to be this little book, it'll be like pocket size and you can read it in two directions, and just seeing her eyes glaze over. There's no money in this. There's no money in this at all. This guy is a raving lunatic, and his profitability has really plummeted here. We thought he was going to fail, now we know this is. But rather than getting discouraged, saying, well, that's okay, I don't need to publish with that publishing house. Thank god they published a couple of my books, but I can do this on my own. And I collaborated with this great artist who I worked with at a newspaper in the mid-nineties, and I always loved his artwork. And once I saw the covers, I was lit up. They were so beautiful.

I love the Frequently Asked Questions at the end of the new book. And I want to know more about why you don't like to call yourself a writer.

Well, it's not that I won't call myself a writer. It's not the first thing I would say, because it sounds pretentious and it's like a mantle that I don't want to carry. I would say that it's true, I spent a lot of time writing, but over the last three months, people say, what are you working on? And they're like emails to schools and administrators. That's what I'm working on.

That's writing too, Steve.

I mean, I know that it's writing, but it's not writing in the way that the interlocutor means. They mean, are you a novelist or is your name on the spine of a book? So what I prefer to think of, because when people ask, ‘Am I a writer?’ or ‘When can I call myself a writer?’ It's such an anxious question. Maybe that question is its own diagnosis here, that you're jacked up about this question of legitimacy. And so maybe it's time to step back and, rather than figuring out what the noun means and when you're it, focus on the verb writing. I am in the act of writing. And break that down further: I'm just making decisions about words and punctuation and paragraphs and plots. That's what you're doing. You're a decider. And that takes it from a passive, status-based, title thing to a much more realistic view of the hard labor you're doing when you can get away and focus yourself. And also that you have to do alongside the work of parenting and the work of being a partner and the work of being a citizen in the world and taking care of aging parents and whatever else is weighing on you. You have to go and try to word-decide. And that maybe isn't responding to the question in the way that the person asking it wants from you.

They might be a little confused.

That’s right, but then they'd just be like, all right, that person's kind of fucked up, I'm going to talk to somebody else at the party. And you’re like, great, we've both saved ourself a lot of time and energy.

I was struck by it because it's so different than the answer that people usually give, which I alluded to above and which is much more inspirational. You’re a writer if you write. Even if it's emails to your kid's school, you are a writer.

Yeah. I mean, I get it. And I'm a big believer in people esteeming what you're doing and who you are. I just think that the question itself arises from an anxiety that the answer should address.

Order your copy of this beautiful book here.

So true what you write about ambition not waning — but rather becoming harder to ignore! — after kids. I walked away from that piece thinking "damn this woman has a long fall down to earth if she ever has children." It's not something you can optimise!