"What If I Just Let It All Be in One Big Pot? What If I Integrated Myself?"

A Conversation with Maggie Smith

I recently took a workshop with a wonderful instructor who, at the end of the final session, half-jokingly encouraged us to mine other people for good material. “Give yourself permission to be a piece of shit,” he counseled, “you’re a writer, go out there and exploit.”

I bring this up because if you’ve been here for a while, you know that I spend a lot of time thinking about the boundaries of what is ours to write and what isn’t. Our stories always overlap with other people’s stories and so, particularly if we are writing personal essays or memoir, we inevitably rope the sometimes innocent and often unwitting into the narratives we prepare for other people’s consumption. “I am unthreatening in ordinary life,” Janet Malcolm once said, “but when you write about someone, that’s the threat.” Or, as Joan Didion put it, “Writers are always selling somebody out.” In other words, writing inevitably involves betrayal or, in my instructor’s parlance, being a piece of shit. You know, the Bad Art Friend of it all.

To whom do we owe our allegiance when we write? Is it to our writer selves? To the art? Or is it to the people we write about? Does the answer change when the people we write about are also the people we brought into the world in the first place?

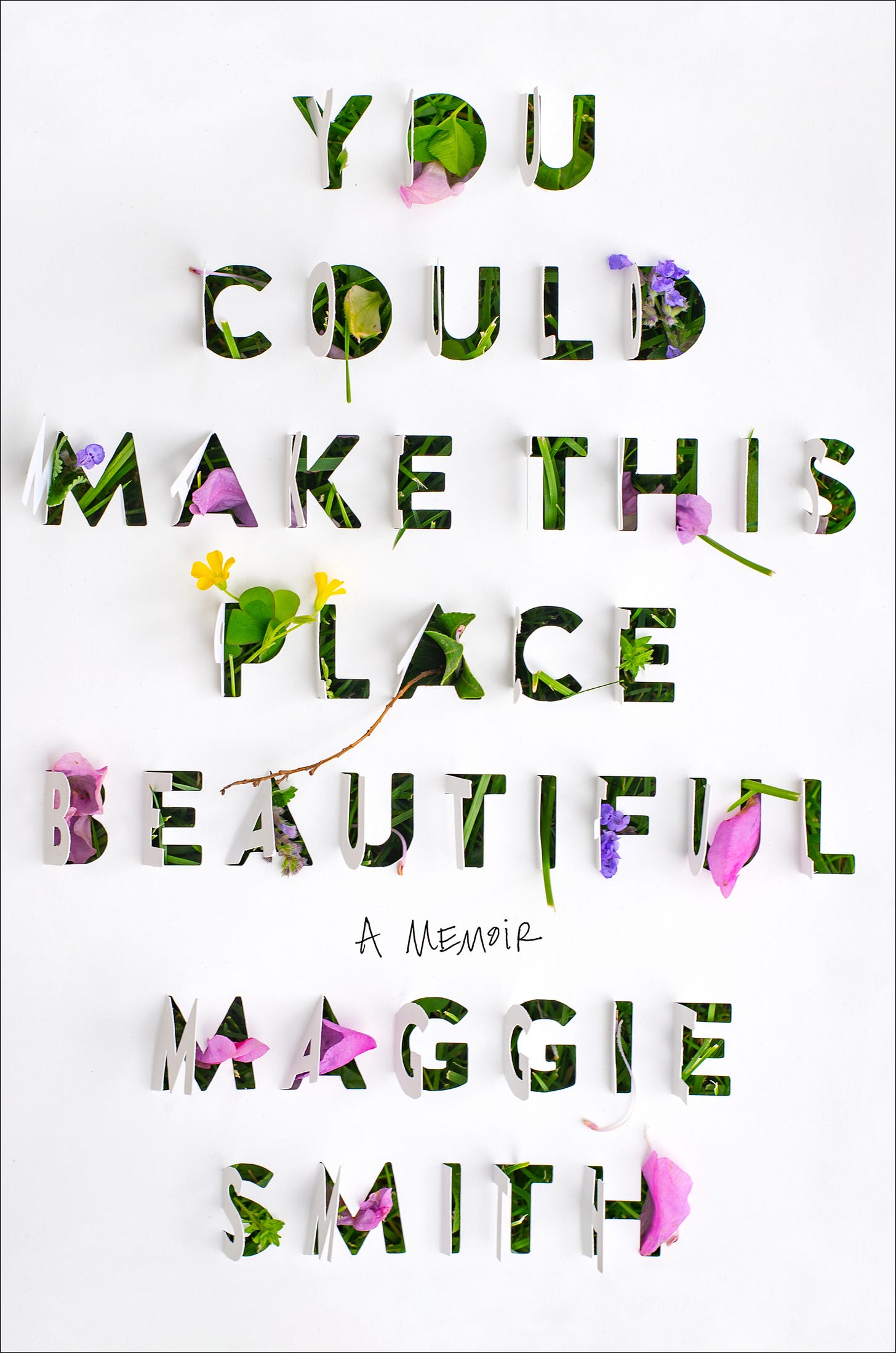

Of course, it’s easy to moralize and say that no one should ever write about their children, who often cannot meaningfully consent to being written about. But I do believe that the world is a better place because of writing that takes on the thorny narratives of home and parenting and care. Maggie Smith’s poetry, and now her prose, does exactly this in a way that elevates what we think of as mundane; it shows us the beauty in the dependable. And Maggie’s top allegiance when writing You Could Make This Place Beautiful, she explains in our conversation, was to her children. She found a way to write the book she needed to write while holding back the parts of the story she felt weren’t hers to tell.

You Could Make This Place Beautiful is the story of Maggie’s painful divorce and so it has a built-in villain, an easy mark for betrayal. But in her fragmentary, inquisitive style, the narrative avoids easy recrimination and instead becomes a meditation on the price and the promise of creativity. It becomes another important entry into a new canon that shows us not only that the steady work of parenting is the stuff of art but that art and care can actually be interdependent. The advance for Keep Moving: Notes on Loss, Creativity, and Change, Maggie notes in her memoir, allowed her to keep her house after the divorce. “My work was not the problem,” she writes, “My work was the solution. I kept us here with words.” Read on for our conversation on writing “mommy poems,” what it takes to renegotiate the terms of co-parenting, and why we feel we need to justify writing about our lives.

Photo credit: Devon Albeit Photography

This book picks up around the time of your divorce but you had been a working writer for many years before that, including while having your babies and staying home with them.

I went the sort of traditional MFA route and I had no idea when I did that what I was going to do for my job post MFA. An MFA for me was like a three-year incubation period, almost like an apprenticeship where I just got to write poems, read poems, talk about poems. I got a one-year gig at Gettysburg College right out of my MFA so I moved and taught creative writing at a small liberal arts school for a year. And teaching a 3/3 load, all creative writing, was great but I didn't write myself because there's no Scantron, right?

Yeah, grading and responding to writing can really take over your life.

It's people's plays and poems and essays and there's no way to just be like, ‘it's a B.’ You have to explain why and help them make the next one better. Being a writing mentor is a lot of work and a lot of work that I did not spend working on my own poems. So I did place a book that year – my MFA thesis was my first book – but I really didn't make any headway writing the next thing. I’m a homebody and really wanted to write poems and so I came back to Columbus, Ohio and started applying for writing adjacent jobs and got a job at a little boutique children's book publisher writing flap copy, working with authors, reading the slush, developing projects with the editorial director. I loved it. It was nine to five so when I was done, I was done. There was no prep, there was no grading. I wrote at night, I wrote on my lunch hour, I used their copy machine, I used their mailing system. I used their pens. It didn't pay great but for a period of time it worked out well. And then I went into educational publishing from there. Kind of the same thing, a regular gig with no night work so I could write. I actually interviewed for that job at McGraw Hill in maternity clothes and I'm still shocked they hired someone who was about to vamoose. And when my daughter was two, I got an NEA grant, which is not a ton of money but I live in the Midwest and I had a partner who was working and had benefits so I quit my job and started freelancing. And I've been freelancing since then.

The nine to five job that is engaging but not too engaging, that’s kind of a holy grail for a lot of writers. But you throw kids into the mix and all of a sudden, you're done at five but you're actually not, that’s just when your next job starts.

Yes, you're just on a different shift.

And it’s harder to write on that job.

It is harder to write on that job. And I remember, even when I was on maternity leave and my ex-husband would go off to work, feeling jealous. Because I'm like, you get to sit at a desk, have a little bit of quiet space, have adult conversations, eat a meal, and I'm basically just on the floor doing stuff or walking a baby around who won't sleep. So it got a lot more challenging those toddler years. And then when my daughter was three, I had my son and having a newborn and a nearly four-year-old and freelancing was a lot of very long hours, a lot of very late nights because I'd have to wait until they were in bed to get back

And you were able to write after they went to bed?

I did, but most of it was client work because I was freelancing so I was developing language arts textbooks. I think I put them to bed at like 6:30 at that point so I would get three or four hours of work in at night and then start all over the next day.

Exhausting.

Exhausting. My kids are now in school so as long as I don't have a sick kid, they leave the house at 8 AM together and they both cruise in between 3:30 and four because it's walkable. I don't even have to go get them. And I know I have school hours to get stuff done and that is enormous. It really has come down to writing when the kids are at school. Or like, there was one summer when I had a grad student come to my house for five hours a day, once a week. And I wrote for five hours every Tuesday like my life depended on it because it was the only childcare I had the whole summer.

That's hard to do.

It is not easy but it was the time I had, you know? One thing that mothering has taught me is that I can't be precious about where I work. When I work, I cannot demand uninterrupted space and time. I'll take it when I can get it but I'm very used to working with constant interruptions because somebody wants an apple sliced or somebody wants to know if they can have a ride to the bubble tea place and someone needs $5 for a field trip. If I got completely derailed every time somebody needed me, I'd never do anything. So I think in some ways being a poet and working in little bits that accrue over time – and even the memoir worked like that too – it allowed me to sort of dive in, do a little bit, and then if I needed to step away, it would be waiting for me to come back to it.

Did the kinds of poems you were writing change when you started having kids?

It did. And actually, the longest stretch I've ever not written a poem was the year my daughter was born because I was just exhausted and I had postpartum and I just was like, who am I as a human being, let alone, can I tap into that space? But it was also like, so now what are the poems going to be? There was just so much laundry, so much breast milk. And I just thought, am I going to write about this now? I didn't know how to do it. And only really picking up a bunch of books from a lot of other writer mothers showed me like, oh, well, Brenda Shaughnessy’s doing it this way, right? And Beth Ann Fennelly is doing it this way. And Sharon Olds is doing it this way. And I was like, oh, so I can still kind of write my poems, I can still do this as myself but I don't have to keep my life and my writing separate. I don't have to consider the life as something that's interrupting the writing and I don't have to consider the writing something that's taking away from the life. What if I just let it all be in one big pot? What if I integrated myself? How would that work to integrate myself on the page and in my waking life?

It seems like it’s working pretty well. You’re so good at finding beauty and complexity in what we think of as the domestic and your writing elevates care in a way that we don't always see.

Nailed it.

Now you know. But you’re saying it wasn’t a smooth transition. You had to get there.

Yeah, I think I had to sort of give myself permission to do it. And when I felt like I couldn't give myself permission to do it, I had to seek permission from people I admired and respected who had more books than I did. When I had kids, I had one book. And that's not nothing, I don't mean to diminish it, but it wasn't like I had this whole huge, long, deep, wide body of work and I felt like I was standing on incredibly solid ground and could just keep doing that, whatever that was. I really did feel like I only have one book and it's more or less my grad student poems, these are my 20-something poems, so what is my adult work?

And there's that terror, right, of ‘well maybe this is just something I did once and now this is my new life and I don't do that anymore’?

Oh, yeah. I mean, I knew I would keep writing poems. The question was, will I be writing poems that mean something to other people? I think I've always written about really intimate, personal, sort of particular things, even in my first book. I did have this sense of like, am I narrowing things so much by writing only about this particular lived experience which does feel very specific. And what if other people don't care about that? What if it just doesn't speak to people?

So many writers have those same thoughts. But isn't that crazy when so many people in the world are having that very same lived experience of motherhood? And would probably like to know how someone else processes it? It's just mind boggling to me that we do that to ourselves, you know?

Yeah, and I don't think we're making it up. Someone was just telling me that a mentor of hers who I will not name, a poet I respect, said ‘no dreams in poems, no crying in poems.’ So, if you hear from the outside world, we don't want your “mommy poems,” if you feel like those aren't going to be respected at the literary magazines that you really want to get your work into, if you feel like it's looked at as soft or not as rigorous or not as interesting, or maybe it's only going to be read by women because why would a man want to read a poem from that perspective?

How sad, to only be read by women.

Imagine, how diminishing.

It's so funny, that word rigorous, because what is more rigorous- I mean, I've never done anything as rigorous as caring for small children.

No, exactly. And it's an existential shift. And if you are thinking your way into and through an existential shift, what is that if not rigorous? And I say this to my students all the time, if I had gone to war, would I be encouraged to write about that experience? I think so. If I had been diagnosed with a terminal illness and somehow managed to overcome that, would I be encouraged to write about that? I think so. And yet I think there are some sorts of existential shifts and experiences that we are encouraged not to see as being as valuable in literature and it's completely gendered. And I find that frustrating. Can you tell?

Same, same. We could talk about this all day and into tomorrow but I do want to get to your amazing memoir. Did writing prose kind of creep up on you? I'm interested in that shift.

Kind of. I think typically when I get an idea, it's usually a metaphor or a scrap of language or something. And then I sit down to write it bit by bit. And typically, I think it's going to be a poem always first. That's default. Like Garamond is default, poem is default as a container for the idea. So even the Modern Love essay I wrote, I think I sat down trying to write a poem and I was like, I can't write a poem about looking at my house on Google Maps. This container doesn't fit, it's like being in a tiny, tiny box and bumping my elbows and my head. I need a different space. I need to be able to show more narrative, I need to be able to flash back, I need to be able to give context, I need to bring in research. And it's not that those things aren't possible in a poem but they're not really what I do in my poems.

Was the Modern Love essay your first foray into prose?

No, I think the first real essays I ever published were about postpartum, actually. And some of those are kind of adapted in the memoir. Those were the first essays I wrote because I didn't know how to really do that kind of storytelling and contextualizing I needed to do in order to describe to a person what my headspace was like and what that experience felt like. And so that was the first, but it was like a dip and then for a few years I didn't do anything because every other idea that I had worked inside a poem and I was like, ‘oh, thank goodness I can make this a poem.’ That’s my comfort zone, it's the small pool that I like to swim in.

But you've gotten out of your small pool quite a bit lately, with Keep Moving and this memoir. But the vibes of the two books are so different, not just in terms of genre. Keep Moving is very future oriented. You can tell that you're like, ‘look, I have to move ahead full speed or I'm not gonna make it.’ And then in this book, you have a line where you say “the past isn't a place we can live, but it's a place we can visit,” which I loved. And it strikes me that this memoir is just that kind of trip to the past. You’re finally ready to look back.

Keep Moving was really the book I wrote for me, which is funny because I think it ended up being really a book for other people but the goal was like, okay, I’m not gonna write about or deal with the present reality of what is actually happening because that is not going to help me move forward. What I really need to do in this particular moment is cast my eye forward and try to keep perspective on the difficulty of the situation. So you're right, I hadn't really thought about the different sort of movements of these two books where Keep Moving is like literally pressing forward and then a memoir, by its very nature, is reflecting back. We're having to rewind the tape and sort of replay it and replay it, and rewind and replay it, to kind of figure out what's going on. I didn't know I was going to write, You Could Make This Place Beautiful when I wrote Keep Moving.

How could you? You need distance before you can reflect back.

I mean, frankly, I wasn't all the way through it when I was writing the memoir either, but I was enough through it that I had something to look back on, even though I was still looking around at a lot of it. I'm still looking around at a lot of it. That’s the thing about books. Books end, lives keep going. There could always be another sentence, another page, another chapter, another book, another book. But at some point you have to be like, well, I'm stopping this story here.

That's all for now.

That's it for now, friends. So, no, I didn't know that I would write a memoir when I was writing Keep Moving. I just kind of got through that project and then I hit a period where this book was like the elephant in the room. I didn't know how to write other books until I wrote this book. Poems don't usually do that for me. If I get an idea for a poem, I can jot a few things down and I can always come back to it. It's not like I wake up in the middle of the night and that poem is like, ‘I need to be written now.’ It can wait, it's not going anywhere. This experience, I think because I was really just living it and thinking about it and ruminating over it and trying to figure it out and dealing with it every single day- it's almost like the parenting/life thing. Like how do I live parenting and then write poems about other stuff? It was about integration back then. And so, it's funny, I haven't really thought about that until this conversation, which is what makes these conversations fun, but I do think it had something to do with integration. And actually, Keep Moving as a project had something to do with integration too, which is, I'm living all of this hard stuff and I'm not sharing it publicly and I need to start to tell people that I'm suffering a little. And so writing this book was a way of me being like, okay, I'm a writer, I need to be writing. My mind is so consumed with what is happening in my life, I need to be able to process this, how I process is writing. So I could try to shove this all in a closet and lock it and try to busy myself with other things or I'm going to have to just do the thing and write this because this is where my heart and mind- it's just where they live. And I knew it wasn't going to be a collection of poems because there was too much rewinding.

It wasn’t the right container.

It wasn't the right container. I knew it would be piece-y because I had to write this book as myself. I knew it would be probably be more sliding down on the lyrical end of the continuum as opposed to the conventional narrative end of the continuum. I knew there would probably be some threads and it would probably happen in sort of spiral or waves more than a straight line because that's how the experience felt. But I didn't know exactly what it would look like when I entered it.

There are certain moments in this story, ones that involve your children, when you kind of close the drapes and say to the reader, ‘this is not for you, I'm not going to tell you this part.’ This is kind of an obsession of mine, the differentiation between which parts of a story are for the reader and which aren’t. You also talk about guarding your kids from everyone, including yourself, which I think is related to this kind of material. Where did you draw the line between the parts that are your story and the parts that are their story?

Like everything in writing, it’s intuitive. Honestly, by the last few edits, most of the editing was going through and reading it as if I was my son at 25, my daughter at 30. Like, what would I not want included? And by that point, I had already sort of walled off so much stuff. But what I knew was that my allegiance in writing this book was not to the reader or to my agent or to my publisher or to my editor or really even, in some ways, to my writer self. My top allegiance when I was writing this book was to my kids. They’re the people I feel I have to answer to. And so the one thing I knew I did not want to do in this book was write about their emotional experience or their inner lives, I didn’t want to have any of that in the book. That's their story to tell if and when they choose to tell it. And knowing my kids, they probably will.

The genes are strong.

The genes are strong and they should not be filtered through me, that's not my stuff, you know? So I tried to really keep it grounded in my experience and not speak for anybody other than myself.

The dynamic of being a primary caregiver and also a writer comes up a lot in the book, that thing where you have the job that gets done on the margins, in the little spaces of life between carpools and laundry versus a kind of clockwork office job that also usually makes more money. I think that's a really common experience among women writers who have children. And there’s one part of the book where you describe how your ex-husband's lawyer used air quotes to talk about your work, which is unfortunately how a lot of other people, and even writers themselves, often see this kind of work, like it's a lark or just a hobby.

There's so many pieces at play. There's the piece where your job is creative and therefore feels more like pleasure than work, maybe than someone else's job. So is it really work if you're going and having dinner and giving a reading? Is that “work”? You know, if you're getting paid, it's work, but it sure doesn't feel like work compared to whatever the other person's job is. And then there's the power dynamic of who makes more money. One of the things I think out loud about in the book: is the person who makes more money, in a family with children particularly, sort of like tacitly- is there an unspoken exemption from certain kinds of domestic labor? Because you are pulling more weight on one side and so the other person is expected to pull more weight on the other side. And I guess one of the things I want say, and I think I make this really clear in the book, is that this system is partially inherited but it's also co-created.

Right, do we set it up this way, to a certain extent? Because you're usually not paid for creative work in the beginning, and sometimes ever.

No one is paying their mortgage with contributor’s copies of literary magazines.

Exactly. In fact, you're usually spending more money than you're making. So even if things start to kind of ramp up and you are being paid, as you were, to go to an event, to do a talk, it feels like it may already be too late to change the dynamic.

When I worked in publishing, I still picked up my daughter from daycare and still did all the doctor's visits, all the dentist visits, all the camp signups, all the snack packing. So even with a regular nine to five job, I do think — and some of this is the inherited part — I ended up sort of building my family system or co-creating my family system so that it looked a whole lot like the family system I was raised in, which in some ways didn't make sense because I'm not my mother. These things are things that we pass down and then we take certain responsibilities upon ourselves because that's what we've seen. So if what you've seen in your family is that the man handles taking the car to get an oil change, snow removal, yard work, and, you know, playtime or throwing the ball around, and the woman handles all the sort of big picture tasks like the meal prep and shopping and the hands-on caretaking and all of that stuff, if that's what you've seen your parents do, then there's a higher risk of you recreating that in your family, even if your dynamic is actually quite different because of your education, your professional sort of makeup. And that's one of the things that I've had to sort of reckon with, too: what am my modeling for my daughter and son?

Right, it takes like a lot of effort to not do that. You have to be very intentional.

Well, and I wanted to and want to, so that's the other thing, right? If I could go back and do it differently, I'm going to be really honest and say I wouldn't do it any differently. I'd still do all the doctor's visits, I'd still do all the dentist visits. Because I like to be there, I want to go to the field trips, I want to make the Valentine's Day treats. And I don't think it's because I have Stockholm syndrome. I really do want to do those things. But the problem really is if you want to do those things and then something happens to you professionally that makes doing those things all the time difficult, you need to have some flexibility or a little bit more of a percentage shift. And then what happens is you're trying to renegotiate the terms. And it’s never too late but it can be too late if only one of you is interested in renegotiating the terms.

That's the key there.

I had somebody reach out to me recently who read a galley of this book, who I know personally, not well. He is a man and he is a physician, and he said ‘after reading this book, I sat down with my wife and we had a discussion about what the load is for her, what the load is for me, what her dreams are. Turns out she wants to do some things professionally that would cause some kind of different shifts in our family. I wasn't even aware because it seemed like it wasn't on the table, but since I brought it up, now it's on the table and we're really having this conversation.’ And I'm like, something I did not expect from this book, but amen. If you have a partner who can recognize that there needs to be some sort of renegotiation of terms, whether because the kids are getting older or because you want to do something or because your work is becoming more demanding or whatever the thing is, I don't think it's ever too late, but it is too late if it only interests one of you.

In the book you bring up the idea of this story being useful to your readers. And I have to admit that I had a kind of knee-jerk reaction to that because it reminded me of that idea that we were just talking about, that we have to be able to produce something in order to make this work worthwhile.

Justifiable.

Yes, justifiable. That is definitely a word I use all the time. And it also kind of reminded me of about some of the self-help talk around Keep Moving. People get really agitated over the boundaries of genre and I remember reading some of it and thinking, you know, isn't all writing kind of self-help in a certain way? Don’t we look to it for…something? But what kind of use were you thinking of when you were writing it?

It's interesting that you bring that up because I think this was part of the conversation I was having with myself in the process of writing this book and, again, having that same conversation I was having with myself when I had newborns, which is, what are we told? And what are we told about memoir as a genre, particularly as it relates to being a woman and writing about one's life? Is it self-indulgent to write about one's own personal experience and expect anyone else to care? And so where we go with that is, well maybe I can “justify” writing this book and spending this many words trying to talk into my own mind and my own experience if it does something for someone else and it's not “selfish.” It comes from a deep place of needing to sort of account for one's work.

I relate to that so deeply but I wish we didn’t have to account for it. Why does it have to be useful? Why can’t it just be beautiful?

Yeah, it can just be art. It doesn't actually need to be fashioned into a tool and yet why is it such a gendered experience that we think, you know, ‘oh, and look, it's also a parachute that will save you! Look how many things it can do!’ Like a transformer, you know? Maybe it can just be a book.

Maybe it can just be a book. And you’re right about the gender aspect. Men seem not to wrestle with this.

Yeah, because they don't need permission. And so if you have this deep feeling in your gut that you need permission to do what you're doing and that it needs to be useful and that it needs to be valuable in some measurable way in order to justify the time and expense it took to do it, I mean there's so much internalized stuff that comes out of that. I don't think that a lot of men are having those kinds of feelings. It must be nice!

It must be nice. I feel like a broken record, I talk about this all the time, I should probably move on, but it's just endlessly fascinating to me the way- you have a daughter, I have three daughters and it's like, how do I change that? Do I get to change it?

Like what kind of reset button do we get? Also, for our sons. Whatever I'm modeling about what I do is also being modeled for my son and it will also affect his expectations. This is the stuff I think about. And so, later in the book I realized that I have to just trust that experience is instructive in and of itself, and that whatever I'm handing you, you're going to know what to do with it. There's no fortune cookie wisdom, I don't have to package it in such a way. I don't actually even have an elevator pitch for this book. If people ask me what this book is about, I'm like, ‘read it.’ There's so much experience in it I'm not sure how to even summarize. My goal was I wanted to feel better by the time I got done. That was my goal.

And did you?

I did. And not in ways that I expected. I thought I would feel better when I got done because I would have it all figured out. Wouldn't that be satisfying?

Oh, that sounds great.

Yeah. I did not have it all figured out when I got done writing it but the process of writing it was so freeing for me and healing in a way that I hate. I hate the idea of healing, I'll just say that. I find it very uncomfortable. I think more along the lines of endurance. I knew that I would always feel pain around this time in my life, but I didn't want to suffer. And I do think there's a difference. And writing about it and writing into it and unpacking it and coming to some revelations of my own through the process of writing, it helped me get past the rumination and suffering stage. So it’s not going to have the same effect on a reader that it had on me because I was writing into my own experience. I have no idea what any individual person will walk away from this book feeling but I hope that it's less alone.

Order your copy of You Could Make This Place Beautiful here.

This was SUCH a wonderful interview ❤️

So honest!