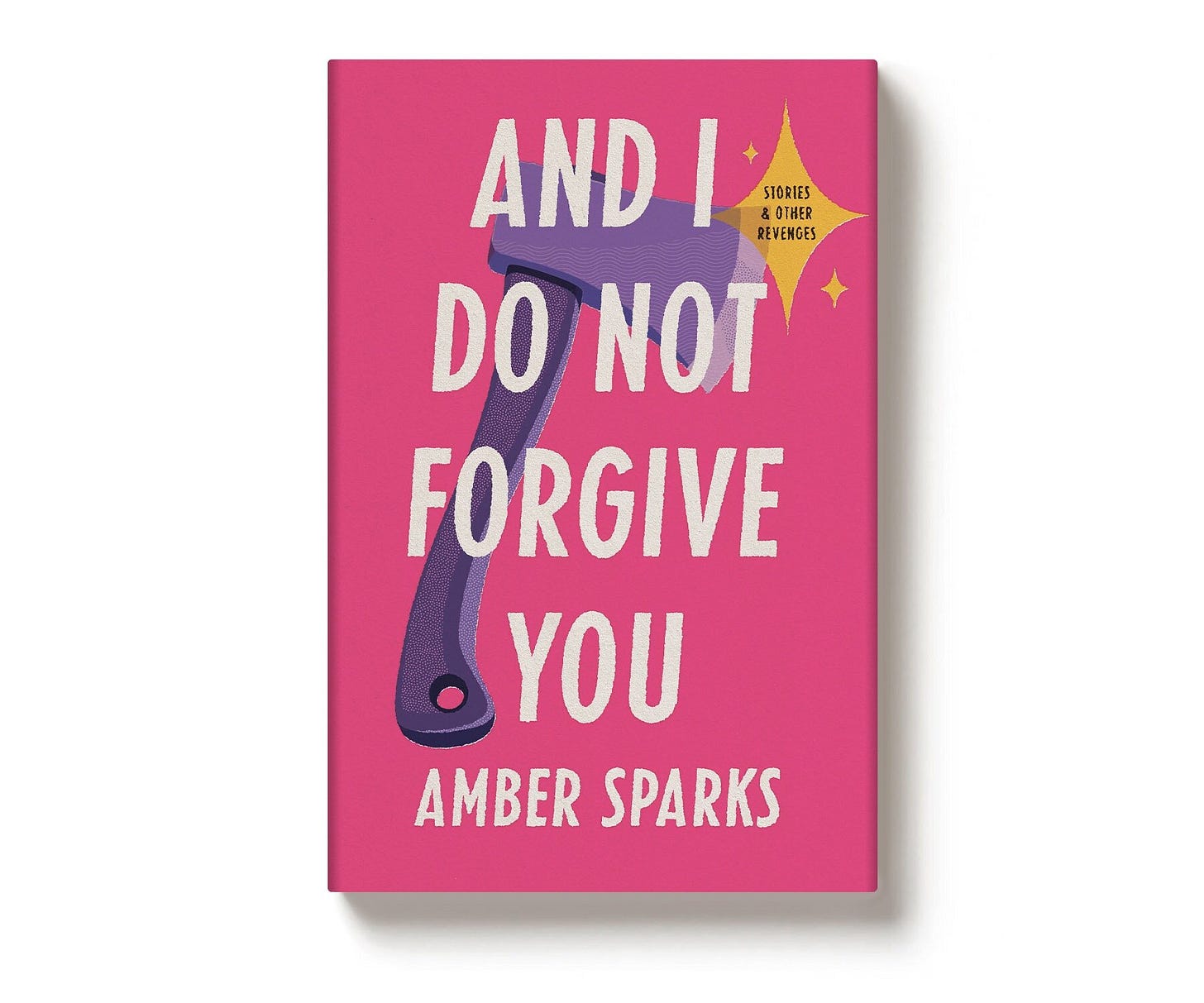

When I first thought up this newsletter, I had a relatively short list of dream writers to interview that has since grown. Amber Sparks was on that original list, and not just because of her mesmerizing short story collections, the most recent of which is And I Do Not Forgive You: Stories and Other Revenges. She also has a Twitter presence that, especially this past year, has been equal parts validating and comforting in its blunt descriptions of trying to write with a young child constantly by her side. And, as with Sparks’ stories, the comfort comes not from her telling you that everything is going to be OK (apparently that’s not a thing) but simply from the artful articulation of a problem with no ready solution. So it was an absolute pleasure to talk to her about carving out a literary career when you have a child and a full-time job instead of an MFA, writing angry women, and the perhaps gendered challenge of thinking of writing as a job instead of as a hobby.

I first want to say that your short stories have continued to haunt me, in the best way. This year I've actually thought a lot about the time travel story from The Unfinished World because the daughter of one of the characters dies in a pandemic, and also really because of everything in the story, you know, living in this scary world and wanting to change it.

You know, it's so funny, I haven't thought about that story in a while because I haven't thought about that book and I totally forgot that his daughter dies in a pandemic.

When I was thinking about it again in preparing for this interview, it occurred to me that many of your stories seem to be a way to metabolize much that's painful and terrible about life and to look at them in an off-kilter and unexpected way, to inject some form of whimsy into what’s frightening. So I guess my first question is, has this insane and off-kilter year been fruitful for your thinking or is it too much, even for you? And I guess that's another way of asking, have you been writing this year, which I know is also the worst question.

Yeah, it's funny because I've actually struggled with that a fair amount because my writing does tend to be depressing to some extent, I think. Or, you know, look at darker subjects. I've been working on a novel and it is something I've been thinking about a lot because I keep thinking, my god, I wouldn't want to read this. And people want something joyful and they need something that's hopeful. And I seem to be somewhat incapable of writing that. So it's interesting because I hope that it is changing the tenor of the novel that I'm writing just a little bit. I don't think I could ever write something that was like a Hallmark movie, per se, I just am not capable of it. There's a skillset there that I don't possess for sure. But I think that I'm trying to let my characters have a little bit more happiness. And I was even like, oh, I should have a character that actually ends up happy in the book, somebody deserves to! And I don't think that would be happening if it weren't for the pandemic.

So it's pushed you in the other direction.

Yeah, a little bit, I think.

And you started this novel before the pandemic, so you had some momentum.

Yeah, I've been working on it for a couple of years and thank god I wasn't actually working on some post-apocalyptic or pandemic novel because I had been working on it for a while and at this point I'm invested and I can't ditch it. It's actually interesting, too, because it just kind of happened that it's a novel that's mostly set in an apartment building and the main character is actually kind of a shut-in. So, weirdly, it's been fairly easy to write during a pandemic.

A lot of inspiration there, not a huge stretch.

Yeah, the traveling the world or something, it would be harder.

You're good on research.

I did have one research trip planned, to a sanitarium, that unfortunately I couldn't do.

Aren't we all just living in our own sanitariums now?

Yeah, I didn't really need it.

I'm interested in what made you decide to tackle a novel, as a short story writer.

This is actually the third novel I've written. I haven't published the others, though the second one actually got turned into the novella that is in The Unfinished World. That originally was a 280-page novel and it underwent significant revision. It's actually a funny story because I have just the oddest luck, sometimes good and sometimes bad, and I wrote that novel and my agent sent it to all these places and it got rejected everywhere, like most things do. And it went to Katie Adams at Liveright and she was like, I really love this but I feel like she's a short story writer. Does she have any short story collections? Which is the opposite of what they usually say. And I was like, yes I do because, you know, everybody has a short story collection sitting in a drawer that's been rejected. And I sent it to her and she loved it. And she said, I think this this is a novella and I think it goes in the book. She's just this amazing editor.

I was going to say, that's kind of the dream, to have someone come and say, this is what it is. It's good and you can do this thing, and this is how. Or at least it's my dream.

Yeah, and it was like this 280-page novel and we worked to turn it into a novella, which is really difficult, actually, but I think it ended up so much better. So I had really written two sort-of novels and I'm just really stubborn and was like, I'm going to write and publish a novel. I don't care, I'm going to do it. At this point, it's just a thing that I have to do for my own sheer, stupid cussedness. And also because I kind of just wanted to see if I could. Anybody who's written a longer short story knows that you love your characters and you kind of wish that you could sit with them for longer. So I was like, ok, I'm going to find a character that I really want to sit with for a long time and write about her.

I wanted to talk actually talk about your path to writing and publishing because you don't have an MFA and I think that parents, especially, who are trying to write can feel a bit of imposter syndrome, or self-conscious, downhearted if they lack those kinds of traditional credentials. Could you talk a little bit about your path and what you found to be helpful or challenging about it.

Yeah, I had a weird path to publishing. Maybe most people do, really. I've always written, like a lot of writers. I started writing books when I was five. And when I was in college I was a theater major but I was an English minor with an emphasis in creative writing so I took a lot of creative writing courses. I never thought about getting an MFA because I was going to go to Broadway and be a Broadway actor. Writing was just a fun thing that I did on the side. And so I was an actor for a while in Minneapolis and I was a mildly unsuccessful actor, I was in a few commercials, one horror movie that stopped production after a month. I loved being an actor but after a while I was so tired because, like every actor, I was working retail and five other jobs and I didn't have any health insurance so I was like, OK, I need to do something else with my life for a while. Sorry, this is very circuitous.

No, please, we love that.

Ok, so my hero, Paul Wellstone, died in a plane crash and I became very inspired and decided to get involved in politics. After volunteering for some political campaigns, I decided to move to D.C. and get my master's. I moved with my husband, who is in public policy. And I was out here and I got a job at a union and it was my first ever 9-5 job that I had ever had. I was almost 30. And all of a sudden, I had all this time.

Because you had just one job!

Exactly, I had been doing like three jobs before and then I was doing plays at night or whatever. You know, I never had any time. So I suddenly found myself with all this free time and it's like what do I do with all of this free time? It's so weird. And so I started writing again. It had been probably five or six years since I'd really written anything. And lucky for me, I found Barrelhouse magazine and the guys at Barrelhouse in D.C. who run this amazing conference and have been doing it for a long time. And I found out that they were teaching courses at the Writer's Center. I took a course with one of the editors of Barrelhouse, this guy Dave Housely, and Dave was awesome and introduced me to the world of writing at the time, especially online and small press and indie press stuff. I was not aware of any of that. I was like, I guess I'll write a story and send it to, what? The New Yorker?

Yeah, it's hard to navigate when you don't know what exists.

Right and at the time, this is about 15 years ago and it was this time when the online literary magazine world was sort of exploding for the first time and there were all these online magazines and people were publishing stuff and there were all of these new and emerging writers who were doing wild and experimental things. There were a lot of writers like Blake Butler and Matt Bell and Roxane Gay who were all publishing in these journals for the first time. I wrote a fan letter to Roxane Gay after reading a piece that she wrote way before she was at all famous. And it felt like there was so much possibility. So I was doing a lot of writing — this was before I had a kid — and publishing in places and really just establishing this network of people and making friends, which is kind of the biggest thing. And after a few years of that, I was like, ok, well maybe I'll publish a book of short stories and I put together a collection of mostly flash fiction because that's what I was doing at the time. I still do a lot of it, not as much as I used to. And I put it together and I sent it around, I sent it everywhere. I didn't have an agent or anything like that. I just sent it to small presses and it got rejected everywhere. And then finally, one of my friends emailed me and was like, we're starting a press, Curbside Splendor. I know you had this work, do you want to send it our way? It was this Chicago press that they were starting at the time. So I sent May We Shed These Human Bodies to them and they loved it and published it, which was amazing. And then about six months after that or something Cal Morgan over at the Atlantic named it the best small press debut of 2012.

That must have been amazing.

Yeah I was like, oh my god. And I guess my now-agent saw that and so he bought the book and read it and called me. And I was at my job at the labor union and I totally thought he was some scam artist. I was like, no, agents don't call you.

I mean, they don't, usually.

Exactly, so I was like, how much money do you want? And then I had to eventually call him back because I talked to some friends and looked him up.

That's hilarious.

Yeah, and he's still my agent and he's amazing. And he represents, you know, like Carmen Maria Machado and Samantha Irby and a lot of really great people. He has good instincts, I guess.

He chooses well! That's such a cool story.

After that I published a book at Liveright that he got me and that was also really difficult as well. It wasn't like, well I got an agent, now it's all smooth sailing. That was rejected most places too because the stuff that I do and short story collections, not everybody loves them. I finally got that one published, thanks to Katie, and Liveright has been a really great home and agreed to publish the last one too, which also wasn't a book that I intended to write. I was working on the novel and I get really bored when I'm working on a novel and I usually end up producing a short story collection as well.

Sometimes you just need a break from things that you come to hate.

Exactly and it was a couple years after my daughter was born and I was writing that one late at night while I was just pissed off reading the news.

You found your way to publishing through small presses and building community and I would love to know whether you think those same opportunities still exist for people without MFA connections who want to write. What is your advice to people who are trying to build a writing community outside of the traditional avenues?

Not only do I think the opportunities outside the MFA still exist, I think they’re more plentiful than ever because of the internet, local and online classes and conferences, and social media. There are so many ways to form community now that just didn’t even exist when I was first starting out.

Right, and along with your non-traditional route to publishing, you are a writer with a whole other full-time job, which I think a lot of people who are trying to publish also have. Can you talk about that? How do those two interact? Do you keep them very separate in your head?

I do keep them very separate. My other career is in labor communications and so I worked at a labor union for years and now I work at the Labor Federation. And so, you know, it's funny because it's a whole separate track and it's also a job that I really love for totally different reasons.

And you do digital strategy there, which tickles me because it seems so of the moment and so many of your stories draw on our oldest fairy tales. I love it.

Yeah, there's a lot of sort of internet stuff that works its way into my stories, too.

Yes, it’s that wonderful and unexpected mix.

It's a weird thing and I do tend to keep it pretty separate. It's not like I hide it from anybody but it's just, in D.C. people tend to read a lot more nonfiction or political stuff so you never know how people are going to react if you say you write weird short stories. And so it's always really funny to me because this last book got some nice reviews, including one in the Washington Post and I had co-workers who were like, are you a writer? Was that you? So it feels like a weird almost dual life sometimes. But I like it that way. Sometimes I fantasize about what life would be like if I didn't have another job and I just wrote all the time but honestly I probably wouldn't get too much writing done.

I'm a big believer in a full plate, for better or worse. I think I get more done when I have a packed schedule.

I think I do too. I never got more done than in the months right after my daughter was born and I was frantically editing my first book and working on this other book.

How was the experience of writing and publishing a book with a child different from writing and publishing without one? Very similar, I'm sure.

Yeah, it's so crazy. Whenever I give advice to people I'm always like, there is no more perfect writing scenario anymore with kids. And especially now, with COVID. I never have been a person who wrote every day, I just couldn't, and so I wouldn't write for a while and then I'd spend ten hours on a Saturday just writing. Or, you know, I'd take a week off of work and just write or something like that. And now I cannot do that anymore. Once a year — and I'm really bummed that I couldn't do it last year — I usually take a week and my husband watches my daughter and I go off to stay in a hotel or an Airbnb and just write. But most of the time I can't do that so my writing habits have just changed so much since then. And I've actually maintained this during the pandemic, thanks to my husband, but every Saturday I still get four or five hours to write. It's harder now because I'm just in the bedroom as opposed to in the coffee shop.

Yeah, that physical distance really does make a difference.

It really does because now my daughter knows she can just come in and bug me for stuff or I can hear her playing. I live in a small apartment so there's not much separation. I still have it, which is nice. But as soon as she was born, honestly, you just don't have that luxury of 'I'm going to set aside five uninterrupted hours during the day,' so it's all about being able to write when you can. And for me, especially having a full-time job, I always tell people I started using my phone and the Notes app on my phone and I almost wrote the entire last book on that Notes app while I was commuting or late at night.

Someday someone will have to do a survey on writing parents and the Notes app because I'm starting to think it's the only way.

Yeah, it's interesting. Now that I'm home, during COVID, I've been writing more longhand, in notebooks. It's a weird thing that I'm trying to do to fool myself that I'm not writing a novel. But I still do end up writing a ton of stuff in the Notes app because the biggest thing I've had to adjust to, like all parents, is that there's no sort of perfect time anymore and if something comes to you and you're like, I have an idea, you better get it down now.

Otherwise it's completely gone. You can't wait until you’re sitting at a desk.

Exactly.

I read acknowledgments like I'm looking for buried treasure, like, how did this person do this.

I always do too.

It’s a way to try and decode a process that seems so impossible. And it's really interesting because as I talk to more and more writers who are parents — and so far it's just been moms and I'm actually dying to talk to dads too, I need to get that scheduled — that theme of the supportive spouse comes up again and again, and I see it in acknowledgments all the time. You know how men used to thank their wives for typing their manuscripts? It feels like the husband who takes the kid for hours on a weekend is the new literary amanuensis. And I'm not sure how to feel about that.

It is weird. I know what you mean because with men back in the day, it was a given.

Right, they're not thanking their wives for having and caring for the children, keeping them alive. They're like, oh, you typed my manuscript, thank you so much. Whereas we're like, thank you for taking your children for a little bit of time.

I think for me, I'm really lucky because my husband actually does I would say 90% of the housework. He's like literally washing clothes right now. So I actually feel really lucky about that and so it's a weird thing, I think, because my writing does not support our family, you know?

I think that's it, right?

I think that's the difference. Even though it's not necessarily a hobby — and in fact money from my writing generally has tended in the past to pay for vacations and things like that, smaller things — it is not like I'm the breadwinner through my writing. And so I think because of that it feels like it's still a thing that is on par with, for instance, I give my husband Sundays- he's like a vinyl nut and so on Sundays he listens to vinyl and he is cataloguing records and things like that. And on Saturdays I do writing and that feels fair. But yeah, it is a weird thing and I feel like that is the difference. Because back in the day these male writers were like, 'well this is my job.'

Right, like, 'how do you expect to pay for the food that you feed our children?' It's definitely a money thing and I'm interested in your take on it because I've written with very little personal income and then with no personal income and then decent income and I feel more entitled to time now that I’m bringing in more money, even though it's the same time, right? Does it change things for you? Because I see this a lot with writers who are moms trying to write while they’re home with their kids, there's this guilt of like, well I'm not contributing monetarily so how can I claim this time?

Yeah, I definitely think I would feel differently if I wasn't working full time and bringing in actual money to the household. It definitely helps, the money part is such a big deal. My husband has never been anything but supportive of writing and he wouldn't put a price tag on it. But, yeah, even just the fact that I have gotten to the point that I can make an advance on a book that can then pay for some of our taxes or we can go on vacation with. Or, actually, the last few years my book money has paid for things like summer camp. It's a weird thing and it will justify stuff like tonight, or doing readings or taking time away in my own head from my daughter to go and do whatever reading or writing-related thing I'm doing, or teaching a class or something like that because it's like, well, I'm making money so it's fine. It's actually really fucked up.

I think about this all time, especially in terms of when people feel comfortable calling themselves writers. Even if you write every day, until you're able to monetize it, you're kind of like, well I'm not really a writer.

You're totally making me think about this and it is really fucked up.

But even if you think of it as a hobby, it's a hobby that might eventually make money, it is a career that people have. And other people with non-lucrative hobbies still claim that as an identity and as writers we're so reticent- like, I don't feel like I can call myself that because nobody has paid me. Or maybe they paid me like six months ago but can I still call myself a writer because I haven't published anything lately?

Yeah, until I published a book I never felt like I could call myself a writer, for sure.

I love the subtitle of your newest book, "Stories and Other Revenges.” And you did mention that you were writing these stories from an angry place, in reaction to the current events of recent years. Reading the stories, many of the women are victimized and so their anger is understandable, or forgivable you might say, but maybe it's that they hold onto it that pushes them into perhaps 'unlikable' territory. Did you have any fears about writing these kinds of women?

I think I got comfortable with that a long time ago and kind of figured out that it was, for better or worse, what I was writing because it was what I was interested in. I've never been interested in protagonists that were too good or too easy to like. It's one of the things that drew me to writing in the first place, the fact that people are just so weird and complex and have so many sides and a lot of them awful. So I was always very interested in exploring that and it never bothered me. I think the thing that was interesting about this book was it was the first book that I wrote that was all from the perspective of women, with the exception of like two stories I think. And I was a little bit worried about that because everybody tells you, don't do that, you're going to lose like half of your audience or whatever. And I'm like very baby GenX so when I was in school or first starting to write, I was very much brought up in this idea that you didn't call attention to the fact that you were a woman writer. You wanted to be as much like a man as possible. You wanted to read Bukowski and talk about the Beats and all that kind of stuff and it was really ingrained in me for a long time. And it really took like, Kavanaugh and Trump and MeToo and all this stuff and having a daughter for me to just be like, you know what? I don't give a fuck anymore. I do not care if men read this book. And I was really gratified by my publisher because I was worried that they would be like, yeah, we can't publish this. And they're all awesome women and they were like, we love it.

Finally, someone's doing it.

Yeah, it was nice but I was a little bit freaked out about the prospect of going so unabashedly unlikable women in particular. And it shows in the Goodreads comments. You're never supposed to read your Goodreads and I stopped after a while but they had never been particularly problematic before and then all of a sudden with this book I'm just getting like these really nasty reviews from men who are just accusing me of writing political polemicals. ‘She should have just written a political book about how much she hates men if she wanted to say that,’ you know? Things like that. But at this point, you know, it feels so cliched to say it but having a kid in so many ways just made me not care about so many things that I cared about before.

For all the things it takes from us — time, brain cells, and body functionality — it does put things in perspective. I also found myself much more willing to fight for things. Which brings me to one of your stories, titled "Is the Future a Nice Place for Girls." Do you think that the future is a nice place for girls? Because lately it feels like we haven’t made as much progress as we might have thought before the pandemic. The fact that working women, moms have seen that when there's nowhere to send the children, we can't do what we need to do.

Yeah, that was a story that was really weird and personal and interesting to write. And it was funny because I actually had this back and forth with my editor about the title and the punctuation in the title. She was awesome but the question was whether or not we put a question mark at the end of it. And there's no question mark at the end of it right now. The idea was to give it that sort of flat affect of speech on the internet in some ways but also is it a question or isn't it a question, I guess was the back and forth that we had. And I kind of decided that it's not really a question, it's sort of more of a statement in a weird way. Like you were just saying, the last ten months have really been depressing in a lot of ways as a woman. It's been depressing in many ways for many reasons but as a woman and as a mother, I've really felt like so much — and others have written more eloquently about this than I can speak to it — that so much of the progress that it felt like we had made has been undone or has proved to be fairly illusory, and that we really are alone in so many ways. And there is no support system here, really, for mothers. And that so much of what we thought we'd built was very much based on a whole class system where upper-class white women were able to hire the labor or women of color and other women to care for their children. And once that sort of fell apart, it was like, that's it.

Or even just school, you know, that we were all relying on school to keep a job.

Yeah, so there's a lot of pieces where, as a white woman myself, I've really been thinking hard about a lot of this and a lot of the ways that I feel like my own feminism has in some ways changed or opened up, I hope, to looking at greater solidarity. And as someone who works in labor I've obviously been thinking about that forever, too. But I think that in terms of the way that people are really very happy to have women return to these roles of caregiver, homeschooler, whatever it is at home, there's a fair number of people in this country who have been perfectly fine to see women return to those roles and leave the workplace. And not all of them are conservative, either, I would say. So I think we have a long way to go but on the other hand, part of the reason that I wrote that story was actually because I was feeling really shitty about the future for my daughter. And I'm a huge medieval nerd and I read a lot of stuff. I'm literally watching a series about the Black Death right now with my husband. And weirdly enough, I actually comfort myself a little bit thinking about how things were back then and reading about it because obviously things are better now than they were then, it's unquestionable. And so it was sort of in a way a little bit of a lullaby to myself to try to be like, ‘look, it's slow and there's a lot of backwards, forwards stuff that happens but things are moving forward and they always do and things are getting better for girls.’

Incremental change is still change.

Yes, exactly. And that incremental change seen from a great distance is not incremental and that's something too.

***

Order Amber’s new collection, And I Do Not Forgive You: Stories and Other Revenges here!