[Sending this post again because I think Monday’s outages impacted delivery - apologies to those getting it twice]

The internet loves to remind me that wonderful and famous writers had very specific schedules and routines. It’s helpful when the internet does this because I am also reminded that part of the mission of this newsletter is to widen the lens and showcase the books written by people who start the day making scrambled eggs for cantankerous three-year-olds instead of lighting a candle and invoking the muse and to shine a light on the ones who write on the sidelines of toddler swim class instead of swimming 1500 meters after five to six hours of writing.

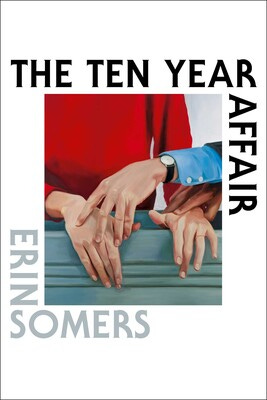

Yes, sometimes a wonderful novel is published because a writer, say, decided to have a baby early in her career and the book is a kind of Hail Mary pass, a bleary-eyed reach of desperation, ambition, and self-confidence. Sometimes a wonderful novel is written in what is left in a day after a full-time job and caregiving. And so it is with The Ten Year Affair, Erin Somers’ novel (her second) about what it means to live a fantasy life alongside the real one, with all its commitments and compromises.

The Ten Year Affair looks deep into the heart of millennial marriage and sees both its absurdity and its lovable humanity. If they gave a Nobel Prize for portrayals of marriage with children, and I was in charge of it, this would be my pick. Read on for our conversation about figuring out how to live a creative life, turning a short story into a novel, and writing round husband characters.

Let’s talk about how you got to this book. I love trajectories.

I went to film school as an undergrad because I wanted to make movies. I moved to LA in the recession and could not, obviously, find work as a 25-year-old kid in the recession. There was no way to make that happen. So I toughed it out for a year there, and then I was like, okay, this isn’t gonna happen, this dream is too hard. What could I do with my life that would still allow me to be creative? What would scratch that itch? And while I was out in LA, I was working at J.Crew on the Santa Monica Promenade, very unglamorous. And my parents would not help me with money unless- I was totally broke, like, destitute and what my dad would do was commission a story from me, instead of just paying my rent. So he would help me out with 150 bucks or $200, or whatever, but I had to write a piece of short fiction.

That’s such a good tactic.

Yeah, and it sort of kept my spirits up, you know? Because it forced me to be creative and not think about myself, really. And I sort of put my LA experiences into those stories. And so when I was rethinking what I wanted to do with my life, and how I could possibly do something creative and make it work, I was like, maybe I should be doing this. So I started writing a lot more, and I went back to New York, and got a job doing dumb editorial work, whatever editorial work I could find, like, working at magazines with zero prestige, the trade world and whatever, but I wrote. And then I applied for an MFA, and sort of worked from there. But it was a very roundabout route. Some people know from the beginning that they want to pursue it and go after it, and I sort of had to find my way.

I’m always impressed with people who figure out how to be successfully creative early on because there’s no road map for it. I’m thinking of June, the main character in your first novel, Stay Up with Hugo Best, who wants to live a creative life, but can’t quite get it going.

Yeah, I went to art school, the film program at NYU, so everyone I knew had gone to art school, all my friends, and no one- figuring out how to translate your urge to do it and to be creative, and to a career that supports you is impossible, and takes decades, and is a hurdle that a lot of people cannot get past, understandably. I guess my message to new writers it it’s okay if it takes a while to find your way.

And so was it pretty straightforward after you got your MFA? How did that play out?

That was 2013. I sold my first short story in the last couple months of my program, and I sort of went from there. I did not go to a prestigious MFA. I did not go to Iowa. I went to the University of New Hampshire because they offered me a scholarship. MFAs are very maligned, but what I wanted out of that experience was to buy myself two years where I did not have to get an all-consuming job. I still worked, I had a job on campus, but I didn’t have to get a nine to five, and I could just really focus. You do not need the MFA if you can find another way to get yourself that two years in that really productive early phase of your career. But I couldn’t figure out how else to do it. So I sold my first story out of the program and then moved back to New York and just, again, took crappy editorial work and started trying to sell stories. And gradually, like, very, very gradually, things started to break open. But along the way, I also had a kid, kind of young. New York young, not young for the world. I was 29 when I got pregnant. My friends were like, are you insane?

Yeah, that’s young, especially for a creative.

Totally. My friends who are 39 or 40 now are having their first kid, and I have a ten-year-old. So that was just adding the most difficult complication into the equation that you ever could. I’m 29, I’m unestablished, I have the worst editorial job you could ever have that makes $28,000.

You know what, just throw a throw a baby on that, a newborn baby.

And have a baby. That’s where I was at. I don’t even want to know what my family thought I was doing, but I do not regret that decision. We have our amazing daughter, we knew we wanted to be parents, she was planned. It was a silly plan, but she was planned.

Well, it worked out, though obviously you couldn’t have known that at the time.

Totally. And then, I mean, it got even crazier from there, because we were super-duper broke. My husband also was doing dumb, underpaid editorial work, and we lived in a Brooklyn apartment, and we were like, we have this baby, and we are in trouble unless something changes. And my idea was, like, give me a year, and I’ll write and sell a novel. And that’ll fix things. And that’s a terrible plan, because you cannot rely on the idea that you’re gonna sell a novel as a life plan, right? Like, it’s so hard.

But it’s so ballsy, I love it.

It was just this crazy, romantic scheme, and my husband was like, okay, do it. And I still kept my job. I took the year when my baby was between one and two and just managed it, somehow. I probably couldn’t even access what that took at this point in my life.

What was your childcare situation because, also, childcare in New York can bankrupt a person.

Yeah, we had a part-time babysitter, and then I would work from home and manage the kid. I just don’t even know how I swung it. I also had a fellowship at that time. I was a Center for Fiction Emerging Fellow, so I had a little office space to use, and I got a few thousand dollars, which immediately went to pay our rent. So, people are like, what did you spend it on?

Basic sustenance.

We just paid the rent, man, nothing fun. So I took that year, and I finished the novel, and I was like, okay, now I’ll sell the novel. And just miraculously, the plan worked. I got a really great agent, my first agent, Esther Newberg, who’s really wonderful and reps cool people. And I went from having this novel draft and no agent to having this amazing agent, and a book deal within one month. The way it turned our life around was just wild. It just totally, totally turned things around. And then I was on my way.

But you’ve kept a paying job the whole time. Now you write for Publisher’s Marketplace.

Publisher’s Marketplace has this newsletter about publishing called Publisher’s Lunch, which is a daily, and I work on the newsletter, and I’ve been doing that for about seven years. And that’s a non-stupid editorial job. It’s a very cool editorial job that I’m happy to have. And it fits in very well with my other career aims. But, you know, of course, it’s difficult to balance with the creative stuff.

Yeah I was wondering if being a writer and writing about publishing as an industry ever messes with your psyche.

Yeah, I think of it as, like, a firewall between the industry reporting stuff and the creative stuff. Because I know too much, right? I know too much about what happens in publishing and what happens with first books and second books, and how much things sell for. And I can get really scared.

It’s like when doctors have kids. They’ve seen all the worst things that have happened to children, and then they have one, and they’re like, oh no, oh god.

Totally. Yes. And then it’s also just, there’s no way for me to ever take a break from- when my first book was out, it went fine, but I’m reporting every day on who’s being longlisted for prizes, who’s the MacDowell Fellows this year. And if I start to relate those two things in my mind, like, this could be you, you know- I just cannot think about it as it pertains to me at all. Like, firewall down, nothing to do with me.

That sounds very smart and healthy. So this particular book started as a short story with a long arc, right? What motivated you to write short about a long period of time?

My first book had just come out when I wrote the first draft of the story and I was really interested in whether I could pull off condensing ten years into- the short story is only 13 pages. So, I was really interested in that as a formal conceit, like, can I pull it off? Will it feel too rushed? Will it feel more like an armature than a finished product? So wanting to try to do that was one of the motivating factors behind writing the story.

And what did you have to do to the characters to transport them into a novel?

The main character is where I had to do the most work because there are certain things that are just gestured to in the short story, such as her job. It sort of gestures to the fact that she has an office job that’s a little bit boring, and when I sat down to expand it, it’s like, oh, well, what is that? And who are the people involved with that job, and what is her relationship to it? And every little facet of life that’s just passingly mentioned or gestured to, I had to think through and fill out a lot. And after I finished that with Cora, every character- the husband, he’s unnamed, I believe, in the short story. He is so sketched that he doesn’t have a name. So I had to figure out, who is the guy she is married to?

Right, and that’s such a strength of the novel, I thought, the husband character.

He’s important, right? It was important that he be round and fully realized, and not be an asshole?

Neither an asshole nor ridiculous.

Yeah, I thought I should give him a little bit of dignity, and make him a little bit of a guy you’d like to hang out with. But he was fun to write. I had a lot of affection for him. He’s sort of sweet.

Not to get into spoilers, but a short story requires a different kind of ending than a novel. Was that a challenge?

Yeah, it was. I knew I had to, in expanding it, push the conceit further, the dual timeline structure. Otherwise, I didn’t feel I could justify the novel length. What new is happening? What else can this structure do? Otherwise, why are we expanding it here? If it’s done everything it can, then leave it as it is. So I came up with the thing that happens at the end of chapter seven with the timelines, which I will not get into so we don’t spoil it, but a structural thing happens that pushes it in a new direction that does not occur in the short story. But then it necessitated a new ending, because a third of the book has a completely new plot that does not appear in the short story. So it had to end up in a different place and I also just wanted to see how deep I could dig with it, you know? I just wanted it to be more poignant, land harder, say more, say something broader than what the short story said. I thought that it should be a bit of a more ambitious ending.

I brought up June of Hugo Best earlier, and her desire to find a place in the world of art and creativity. Cora kind of felt like a version of June that had given up? I’m wondering how you think of Cora’s relationship to creativity and ambition. I always find it funny and interesting when novelists, who have to be among the most driven people in the world — like, just the right side of delusional to do this whole thing — have to create less ambitious and successful main characters.

I deliberately didn’t give her art as an outlet. Because I do feel that- maybe this is me being overly romantic or silly again, but I do think that art can be the fix that is- it’s neither work nor domesticity, you know? And if you have it, it can become your life and enrich your life in a way that is transformative. But a lot of people don’t have that, a lot of people don’t have a creative outlet, and I wanted to explore what it’s like for someone who doesn’t have that and instead has to negotiate these two poles, either your domestic life or your professional ambition. And if neither of those things are sort of doing it for you, what do you do and where do you go? But it’s funny, because a lot of people reading it sort of assume I’m Cora and it’s like ambition-wise, on the ambition scale, the character Jules is so ambitious, and I’m low-key Jules. It’s presented as something kind of monstrous about her, but I am kind of always working, I’m not really the slacker.

I mean, you don’t write two novels as a Cora. That’s just not going to happen.

But I did deliberately withhold it. I didn’t make her a painter, and I didn’t make her a photographer or whatever. I didn’t give her something because I think that that is a really relatable experience. Not everyone’s a painter, you know? Not everyone is a novelist. But these people still have these inner lives and these same dilemmas and what do you do if neither pole really fits with what you want?

I’m also interested in how you built out the character of Jules.

I loved writing Jules.

Because in the short story, there’s a husband and there’s a wife but the spotlight is on the affair participants.

When I started thinking through what Cora’s work situation was and what her attitudes towards ambition were, I thought that she kind of needs a foil. We kind of need to see the millennial girl boss a little bit because Cora is not that. And so I thought, this should be Sam’s wife, the wife of this guy she has a crush on, to just sort of show the two paths for the millennial woman. You’re incredibly driven or you let all that pass you by. She was really fun. I just liked writing someone who is unapologetic, kind of mean. It’s fun to write someone kind of mean. I liked their dynamic and I liked seeing her through Cora’s eyes, Cora who’s the avatar of the reader, because she’s so sensible and notices when people are being arrogant, and notices when someone’s being ridiculous or whatever. So I liked to watch Jules through the lens of Cora. What does your standard person think of this type of woman?

The book takes place upstate and I’m wondering about the impact moving out of the city had on your writing life.

It’s impacted it enormously. The first novel I wrote was about someone living in New York City and Brooklyn, and then the second novel is set in a town like the one where I live. I think it was enormously useful to my writing to not be in the city anymore. A new milieu, new people to observe, new scenarios. A totally fresh location has really helped and really inspired me. And it’s made me want to write about the domestic in a way that I didn’t see that much. You see a lot of angry novels about women who are trapped in marriages, and you don’t see that many comedic novels about it. And I was like, this is something that I could do, and something that would be really fun to do is to make these little worlds in the Hudson Valley, which isn’t exactly suburban- it’s like these little bougie mountain towns that are really fun to send up, just ripe for a satirical eye. So yeah, it’s been a huge inspiration.

And what was the process of writing the book like? How many kids did you have at that point?

I had published the first novel in 2019 and then COVID happened, and by that time, my daughter was five. And we were like, if we want another one and we want them to share a childhood and have a lot of common experiences, we should do it soon. So I had a late COVID baby. This book was in the works when I was pregnant. I do not find pregnancy conducive to writing. I believe I let myself off the hook. I was like, don’t worry about it. You’ll pick it back up.

Sounds like a hard thing for a Jules to do.

That was what I tried to do, but then also I feel enormously conflicted about that, and also, like I’m gonna miss out or I’m gonna lose- I’m not gonna have a career now, because I’ve messed it up. All these things you tell yourself.

Right, capitalize on the timing, and this and that.

Totally. So then I had the second baby, and then I drafted the bulk of this book, the heavy work, when she was between the ages of one and two. This is the hardest time to write. I don’t know why I do this.

You like a good challenge.

After this book sold, I was like, should we have another baby? And my husband’s like, you’re just trying to make it hard for yourself to write another book.

I mean, can you do it without an infant? That’s a real concern. But during the pregnancy and then during the first year, are you losing your mind because you feel like you should be writing the book? I’m always interested in other people’s thought processes because I have such a conflicted relationship with not doing stuff.

The first time around, I was like, I’m never gonna be able to launch a career. I’m never going to be able to work. I’ve ruined this for myself. It’s never gonna happen for me because of the choices I’ve made. And I did not do well on maternity leave. I was just antsy, and I was like, let me back at it. And all that comes with a lot of guilt, too, because you’re like, I need to be treasuring this. But the second time around, I learned to just chill, and I’ll still be the same person on the other side. With the first baby, you think, I’m not gonna be myself on the other side, or something, some irrational fear where you’re like, I won’t be the same, or I won’t want to, or I won’t be good at it anymore, I won’t be interested. Some fear about being fundamentally changed, or I’m never gonna get another moment again. And the second time, I just knew that I had to ride it out, and I would come through it. And I would eventually be able to work, and I would always work, and that is true. You’re the same person.

I do want to talk about marriage because if you’re writing a book about an affair, you have to do a lot of thinking about marriage and what it means in the year 2020-whatever. I love the conversation Cora has with her husband where she asks whether he thinks of himself as “having” her and what it means to “belong” to someone else, versus, as he says, “we both elect to be here.” There were so many lines that were doing a lot of good work.

I was thinking about millennial marriage and the millennial marriages I know – the people close to me, and my own marriage – and I think that something really great about our generation-maybe it’s every generation, I don’t know, but I know a lot of people where it’s a marriage between friends, where you’re buddies with your spouse. And it’s less about property than it used to be 100 years ago or whatever, and it’s less about social status, and it’s more about hanging out. And so, I wanted to think through what that means, and what that obligates you to. If we’re both just here hanging out, what do we owe each other? We owe each other the best we can do, we owe each other… what? I don’t know, right? And what keeps us here? How deep does it go and what are the obligations around it? I thought that was fun and interesting to think about. And I still really- not to be like, I’m a fan of marriage, but the marriage between friends sort of triumphs in the book and I do sort of believe that. I think that it’s a really beautiful thing.

Yeah, it felt kind of anti-zeitgeisty to me, perhaps best exemplified by this line – I’m going to just keep quoting lines I loved – “It was difficult, but one had to try to imagine an inner life for one’s husband.” People are not super interested in doing that right now, in the culture.

Yeah, the zeitgeist right now is sort of this very- heteropessimism is the term, right?

Or heterofatalism? Which is even worse?

I guess my problem with that is thinking about any group of people as a monolith where it’s like, men do this, men do that. Men are individuals. So I think they deserve our empathy, you know? Though it’s hard, as I noted.

Yes, one must try. The book made me think about the extent to which the problem of being married and retaining, perhaps, a secret inner life is a problem of being human versus a problem women experience exclusively because of sexism or capitalism. The predominant feeling in the culture seems to be that marriage is imposing this problem on us but maybe this is just what it is to live and be married and not a sign that you should necessarily blow up your life.

I agree with that totally, that this is what it’s like to be alive. It’s a little bit unglamorous and you make compromises. You don’t have some sort of fantasy you’ve imagined. It’s just reality. This is not to say that sexism doesn’t exacerbate things and make things very difficult.

And certainly there are marriages that should be left. I don’t mean to say that everybody should stay in their marriages.

Absolutely. But I think that acceptance of marriage being difficult or being an imperfect institution is sort of helpful in seeing the situation as less desperate.

You talked about millennial marriage as marriage between buddies and it’s difficult if not impossible for fantasy to exist between buddies. Joining one’s life with another person’s erodes the erotic, no matter what we call the container. And you do this wonderful thing with the dual timelines where some of the domestic drudgery intrudes on the fantasy.

The crux of the relationship between the main couple, Cora and Elliot, is that it’s lost its eroticism through familiarity, which is, I think, the thing that happens in marriages, and not even just heterosexual marriages. Any relationship, really, if you’re in any romantic relationship, if you move in together, suddenly the person is too familiar. And so the thing she fantasizes about is this unfamiliar new dude but as she grows more comfortable in this fantasy, and it goes on for several years, the fantasy versions of these people become- the same thing happens to them, right? Like, they become over-comfortable with each other, and she’s just sort of replicating a marriage again in this imagined affair, which I thought was sort of a funny layer to it. Also, these people are in their 30s and I don’t see many books that take that decade seriously, especially in a settled kind of way. I think you see a lot of flailing 30-year-olds,30-year-olds who are still seeking, but this idea of, you chose your person and you’re having kids but what’s going on inside?

What was your relationship to the affair novels of yore while you were writing this?

It is kind of a riff on the mid-century affair novel, but placing a millennial woman in the Rabbit Angstrom role of the person having an affair. I had a lot of fun with some of those tropes, with sort of, like, the Richard Yates suburban desperation. What changes when you give it to a millennial? Approaching it comedically, as opposed to, you know, the great tragedy of the second half of the 20th century is that men had to get married and move to the suburbs after the war. So I’m just sort of gently sending all that stuff up by making it comedic and hopefully adding freshness by putting a woman at the center of it. And to go back to that line you said about, like, one had to imagine an inner life for one’s husband, that’s what those novels don’t do about the women, right? The women don’t have inner lives.

I do need to note that the book is so funny. I laughed out loud in bed, and my husband was like, I haven’t heard you laugh at a book in a long time.

I love that. That’s really gratifying. Making it funny is my favorite part.

I can’t wait to laugh again at some point. Are you working on anything new? I know it’s a terrible question to ask.

Do you remember the scene in the book where they are sitting around gossiping about how there’s swingers in town? While I was writing it, I was like, I should write a book about the swingers. So I’m writing the swingers book, and it’s set in the same town, in the same little world. Like, what does it mean to be a swinger in 2025? And they’re really inept at it and why are they doing it, with a comedic approach. You just know millennials are not gonna be good at this. It’s not the 70s, you know?