“My Idea of What Made an Artist Was Unsustainable and Fundamentally Flawed”

A Conversation with Camille Dungy

There are baby geese in our neighborhood lake. I spotted them while driving alone as the sun set on Sunday and I took my two-year-old to see them on our way home from the grocery store the next morning. When we got there, there was ambient chirping and honking and the babies were swimming in a fuzzy line between their grown-ups. If the Wall-E ship captain ever summoned his Buy N Large ship computer to ask “computer, what is bucolic?” this would be the scene it would pull up.

When I moved to this neighborhood about a decade ago, I thought of the man-made lake as a kind of nod to nature rather than nature itself. It was put there, I felt, to simulate a false idyll in an otherwise cookie-cutter 70s-era suburban landscape. In fairness to me, I was a grad student at the time and didn’t know how to turn off the part of my brain that wanted to take everything apart and reveal any authentic feeling to be the outcome of someone else’s nefarious plan.

At this time of year the lake is also home to a bird I call a Blue Heron, though I have zero bird watching bona fides and no idea whether this is correct. It’s a beautiful bird, whatever it is, and each spring I gasp the first time I see it. When I was there with Masha, I noticed that there were two of them. Have there always been two, I wondered, and I just never saw them together? Or has there been some sort of communication between these beautiful birds, the one telling the other about a great spot to spend the warmer months? And what is it about this particular lake that compels this particular bird to fly here each year when the days lengthen and the temperature rises? Is it, in fact, the same bird or a different one that somehow finds its way to this subdivision each spring?

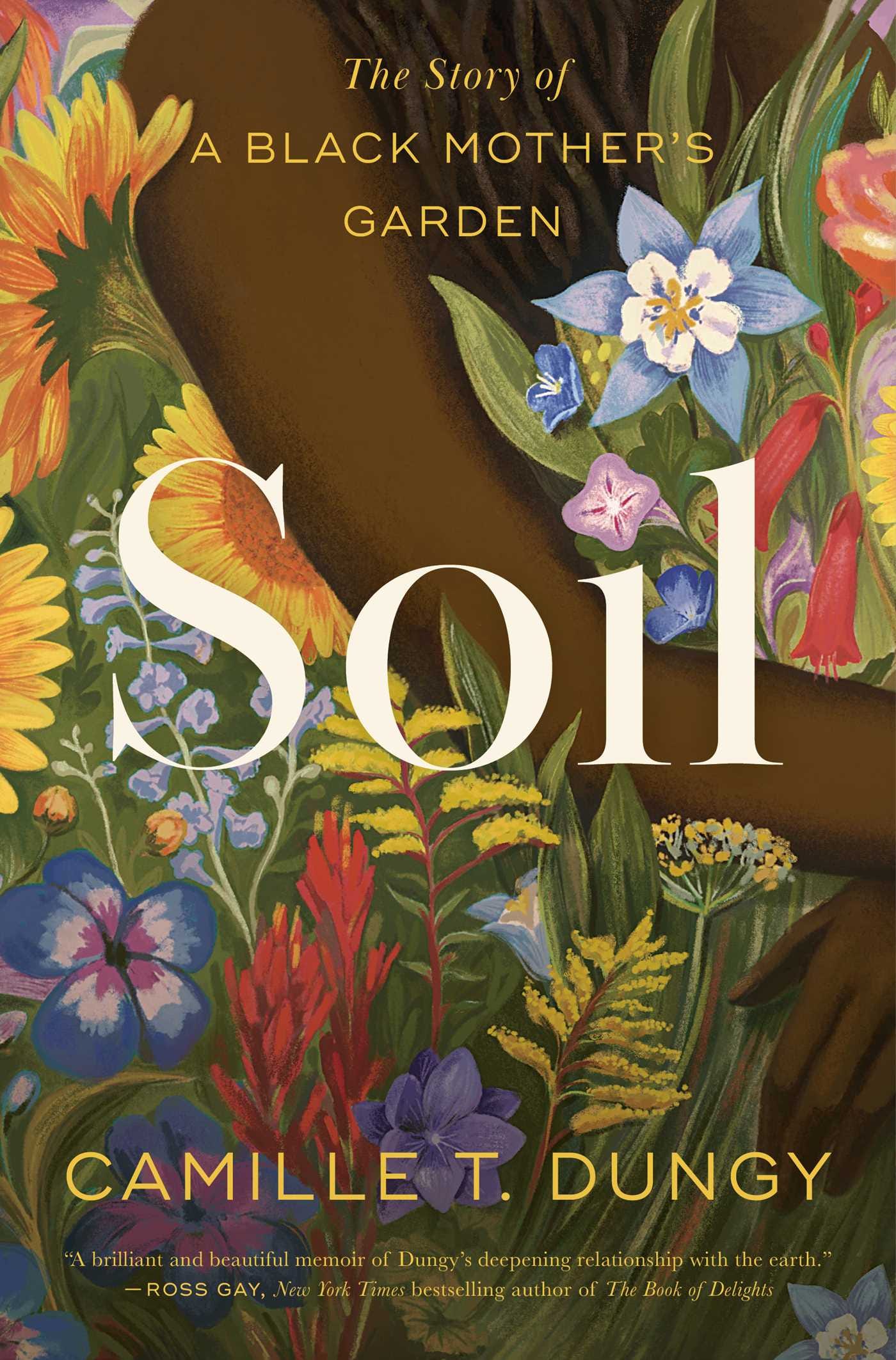

Having just read Camille Dungy’s Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden, I found that I was seeing it all — those fuzzy yellow babies, their parents, the herons (?), the flowers that are blooming where there used to be water — with new eyes. Soil is a beautiful and challenging meditation on growing things in an often hostile world. It thinks about how to be in community with not just people, but also plants and animals, and it aspires to change the way we think about nature writing entirely. Why, Camille asks, do we think of nature and the environment as being exclusively outside our doors and often far afield? Why, when we think of nature writing, do we picture one single solitary person wandering in the woods instead of a mother planting a garden with her child and then going inside to make dinner? Why, in other words, was I so reluctant to believe that a body of water surrounded by trees and populated by various animals depending on the season was not, among many other things, nature?

With Camille’s gorgeous writing lingering in my head and Masha yelling “honk, honk, geese!” in my ear, I thought about all of the different ways the lake has changed over these ten years and how it has stayed the same; how it has its own rhythms and how it is host to the rhythms of others: the geese, the herons (?), the flowers, me and my babies and all of the people who enjoy this lake created by people. All of us keep returning, our changes small and then somehow, over time, great. Read on for my conversation with Camille about restoring domesticity to nature writing, winning a Guggenheim right before a pandemic, and the slow, difficult work of revision.

Photo credit: Beowulf Sheehan

Talk to me about the road to this book.

This is my ninth book with my name on the spine. I was at a little party at one of my daughter's friend’s house, and the small talk conversation, and it was like, ‘Oh, I hear you're publishing a book. Is it your first book?’ And I just sort of froze. I didn't know what to say. How do I answer that question?

I don't want to brag, but...

Right? You know? Then that's what a good partner's for, because Ray piped up and he said, "Actually, it's her ninth."

Everybody needs that wing person to do the bragging they can’t do themselves.

Yes, so this is my ninth book. I have four collections of my own poetry. I edited or was on the editorial team for three anthologies. The most relevant to this project is an anthology that I imagined and edited called Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry, which was the first anthology of its kind to center African American environmentally conscious poetry, and really kind of helped to shape a necessary reframing of inclusivity in US environmental poetry. And then in 2017, I published two books, my most recent collection of poetry and an essay collection called Guidebook to Relative Strangers: Journeys into Race, Motherhood and History. The poetry collection was called Trophic Cascade, which is an ecological term that talks about what it means to either remove or replace a trophy creature, a top predator in a particular ecosystem. One of the most famous examples is the reintroduction of grey wolves to Yellowstone, and the title poem in the collection tells that story of the introduction of grey wolves to Yellowstone. And as I was writing the poem- really it just began, as many things do, as much of Soil did, with my writing into my obsessions, just writing and writing and writing the things that I'm interested in and that I'm noticing. I had seen that story, I was fascinated by it. I just found myself returning to it and playing with it in a poem, and at a certain point I asked myself why do I care about this so much? And I realized that idea of an entire landscape changing because of the introduction, as I say in the poem, of one hungry animal, really resonated with me as a new mother.

One hungry animal, by the way, is an amazing title.

One hungry animal.

I want to use that for everything. It's mother and baby right there.

Mother and baby, right? You're never so hungry as you are when you're nursing. It's crazy. Sometimes I think about the recipes that I found and cooked during that year of nursing, and I had one recipe that I made once a month, it called for 10 egg yolks and a cup of cream.

Oh yeah, you give a nursing body whatever it wants.

I was like, this is the most delicious, healthy thing in the world, and at that moment in my life, it was. So those were the books. As I said before, A Guidebook to Relative Strangers, I was on book tour and nursing, and living in the Bay Area where daycare was just out of control expensive and our hours were strange anyway, since I was touring, and so I just brought her with me.

You wrote that book of essays after she was born?

After she was born.

And then you went on tour, which is…a lot. Were you also teaching?

I was also teaching.

Oh my God. How?

I have an essay in the collection that explains how. It was crazy. I taught on Mondays and Tuesdays, these jam-packed days. I'd be on campus from 9 a.m. until 10 p.m. sometimes, and then I would get on a plane on Wednesday with a baby and would fly around the country and do my thing with her. I flew Southwest a lot.

How old is she? Because there are some ages that-

She was just a little lap child, so she was under two years old for most of that.

But that's a hard age to fly with, in my experience.

She flew at least once a month, every month, from when she was two months old, so I think she kind of knew it. It was just what she knew. She's a dancer now, and sometimes I attribute her insane core strength to hanging on out on my lap on airplanes all the time. Other kids are bolted in in cars, but she was always wiggling around, so there you go, it's because of that. But what I found was that people who would not necessarily engage with me if I were just there in the airplane seat, or if I were in the hotel lobby, et cetera, would engage with me because I had this lovely baby with me. And so I did a lot of thinking about, what are the things that keep us apart in this country? A lot of them having to do with appearance, just purely based on appearance, and assumptions about what appearance then means. And then what are the things that tie us together? And sometimes those are the same things, right? Just in different scales. And so much of Guidebook to Relative Strangers was thinking about those questions from a far-flung perspective of travel. And then, with Soil, there I was completely rooted at home, none of us was going anywhere. I think I'm asking some similar questions about what are the things that tie us together and what are the things that push us apart, and how do we build bridges where there are unnecessary, fabricated divides? How do we break those down? It ends up, in a sense, being a really similar set of questions. It's just that this book is so rooted at home and the other book was about going away.

Yeah, going away, that's so interesting. But the book was conceived before the pandemic, as part of a Guggenheim application?

Yeah, when I applied for the Guggenheim, I did apply with a research project called Soil, and I was going to look at what grew up out of the ground around me. That was, in fact, something I was interested in, but the direction it took completely changed.

Really? How did you think of it when you submitted the application? What did you think it was going to be?

What I think now is that the book would have looked a lot more in line with the conventions of American environmental writing if I weren't forced to confront- I would have looked at the racial erasures, because I've always been thinking about the racial erasures in American canonical environmental writing. But I don't think I would have thought as consciously and doggedly about the questions of what it means to erase domesticity and motherhood if I weren't in that situation where domesticity and motherhood were completely unavoidable and still I was completely focused and interested in these environmental questions. And why was that odd? Right? Why was that not normal for these texts?

Right, the idea of canons, in general, is really fascinating to me, their formation and how we receive them and what we do with them. And that idea of the usual protagonist of nature writing being that lone guy – the white man, usually — going off into the wilderness alone. And the culturally ingrained message that the only way to experience the natural world, or the right way, is in solitude. And also that idea that nature is outside our door, and not in the domestic space. The way we talk about it, we're not a part of it. And you point out that Annie Dillard, in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, cordons off her domestic life from her nature writing, which is particularly interesting because I looked up the dates, and it seems like Pilgrim at Tinker Creek was published a year before she divorced her first husband, who had also been her teacher. Where is that story in all of these walks that she's taking and all of these thoughts that she's having?

Right, and I'm sure that Annie Dillard scholars can tell us the chronology of that, so I don't want to speak on that. I've heard speculation about which came first, the dissolution of the marriage or the astronomic fame that she achieved.

Okay, fair.

And so, I don't know if she was kind of off in this cabin by herself because the marriage was already falling apart. I don't know the answer to that. People do, but I don't know the answer to that. But in either direction it sounds kind of interesting to me to think about. But when Dillard was writing, the moment she would have put any of those stories of what was going on in her marriage into-

She would have been recategorized.

It would have been a totally different book, right? I mean, in a lot of ways Pilgrim at Tinker Creek- and she even says she doesn't think of it as a nature book, she thinks of it as a metaphysical treatise and a philosophical book. And it does have a lot of that, questions about perception and attention and things like that, but it's also kind of easier to talk about it as a nature book, just as with Thoreau, if you looked at Walden but also definitely Civil Disobedience, and really thought about some of his political actions that landed him in jail sometimes- he was engaged and involved in ways, but the hagiography around him is about him being isolated in the woods. It's not about the ways that he is engaged in social protests, right?

Right, people who write things don't necessarily have a say in how they are eventually categorized and what kind of syllabi they end up on. And so what about your original intention with Soil? How did that begin to shift?

There's no way to know because this is the way that that part of my life went but I would imagine so. It took some work on my own part to keep pushing into some of these questions and keep asking myself and become unapologetic in my observations. It also took some work to juggle and balance the writing and the working and the thinking with the child rearing, and so it's always felt to me like I don't have enough time to siphon, to cordon off the different areas of my life. And so if I'm going to be writing about my life, I have to write about my life as I live it, and in that case, Callie was in it. And the more I thought about this, that is the norm for most people. Most people have other people they have to be thinking about. Most people have children or elders or siblings, or something that you've got to be thinking about, and if I was writing a book that- among other things I wanted to build community and conversation with people who are actively engaged in creating a sustainable set of systems for caring for this planet. If that's the case, I need to be talking to most people, not this kind of rarefied few who have some bizarre, privileged, solitary time. And how funny- I mean, you see it, there is a moment in the book where I had a crisis about that. I was supposed to get a bizarre, solitary time. That’s what I was supposed to get for that Guggenheim year.

I felt that so much, that moment in the book where you lose the writing time you had, quite literally, won.

And I didn't get it, and my husband said, ‘Yeah, you and everybody else. What is your thing?’ And it was in that conversation that I had to really reckon with the fact that my idea of what made an artist was unsustainable and fundamentally flawed.

Well, okay, I want to dig into that because you have this great line: “If they value their art, women writers, especially women of color, and most especially mothers, must steal their own time to grow such gardens." We know that we need time to make art. And so I agree that we need to revise this cultural conception of the artist as someone who spends all their time on their art, the eight-hour days you lost out on when the pandemic hit, but it’s also way harder to create if you don't have blocks of time, right? Talk to me about the interplay between those two things, that stolen time, the time you need to steal, and your refusal to cordon off the domestic and the familial from the writing. How did you see it in 2020, when there was no balance, and how do you see it now, that ability to actually get the work done versus that bringing in of the domestic to the writing?

Well, I feel like I have two answers to this question. One answer might address that question that people often ask when there's as many quoted conversations as this book has: how do you remember the conversation and what people said? Part of how I got the writing done during 2020 was I had set myself a rule that I called my 2020 20s, which was that every day I had to write for at least 20 minutes with really, really careful, precise attention to what was interesting around me. And so sometimes those conversations were what got recorded in those 2020 20s, right? And so some of it is just really 20 minutes. Sometimes it was just 20 minutes for weeks at a time would be all that I would have, 20 minutes a day. But it's really amazing what can accrue with that kind of regular attention as opposed to putting off everything until you have time, right? Because I never really had time. I just made this tiny patch of time to accrue that. But the other thing I would say is that probably, if my life looked different than my life does look, this book would have been out at the end of 2021. It would have been a faster revision process and a faster compilation process, and all of those things. So that's my other answer is it took time. Yes, I was able to do it, but one of my- actually both of my texting mates on that chain, where Suzanne went running to the bookshelf, both of those women published books last year, early last year, right? We were writing the books at the same time.

Yes. That’s it.

They're very good books, by the way.

I loved that group text situation, it just felt so familiar and warmed my heart. And it reminds me that this book does so many things, and it does them well. There are so many different and very complex threads to it, and timelines also. How did you figure out the right structure? How did you decide when and how to weave the different threads together? Was that part of the length of the revision?

Hopefully at this point, as it's arrived to you, it feels inevitable and it just always had to be built this way.

It does, but as someone who has, at various points, tried to turn seemingly disparate threads into something coherent, I’m pretty sure that while you make it look easy, it wasn’t so simple to accomplish.

Yeah, it was very difficult. I did have some really great readers, including my editor, Yahdon Israel, who helped me think through some of these questions. I shared an early, early version of this with Sumanth Prabhaker, the editor at Orion, and he was really helpful, and one of the things, when I handed over the sheaf of papers to him, I was like, ‘I have a time zone problem with this book. We are moving all over time, and I need to figure out how to guide people through that.’ In those conversations with Sumanth, Suzanne Roberts, and with Yahdon, I was able to sort of really begin to see what the major time scales were. I made this chart where I could see that seven-year cycle that's in the book and the one-year cycle, and then there's also the cycle of my family history and my personal history. So there's four different times. And how did I keep that centered? Some of it had to do with tense and choices I made with tense structure. It's funny, I teach creative non-fiction. I was teaching a course this semester, and these are just things that you teach when you're teaching the work, but it's harder to apply. But one of them is: where's the end of this story? Because things could just keep going on forever and ever and ever, but where does this narrative end? And so, for me, it was the first killing snowfall, they call it the killing frost, that happened in late October, I think, of 2020, which was really convenient because it's also a time that quelled the fires. It didn't completely extinguish the fires, but it quelled the fires. I was able to sort of know that that was the end point of the narrative, and then I already knew that the story began when I was cruising around town with my realtor in 2013, and there was all this cottonwood and other white stuff falling from the sky that looked like snow and really confused me. And so this movement of cottonwood to snow became the arc. And then also there's the 2020 year, and from the announcement, essentially, of schools closing and my daughter coming home through this time of the fires, which then became metaphorical for all this stuff. We had- it's now the second largest wildfire, that's how quick those things go, but at the time it was the largest- or actually, it's still the largest wildfire, but the one that happened outside of Boulder is the most destructive, because it involved more homes, and proves a lot of the points that I made in the book about this idea of the wilderness-

Right, how do you measure destruction?

Right. What does that mean?

Measuring which is more destructive based on what kind of habitat it’s destroying. That's really interesting.

And you can also hear with that answer that this was a lot of chiseling. Part of why I'm a writer is because I get to keep editing and reworking it, so these oral interviews are kind of interesting to me, because okay, how can I succinctly and as clearly as possible describe something that was a months-long process of discovery?

That's why I do this whole thing, because I live for those kinds of details. Speaking of the fires, toward the end of the book you describe a conversation with your mother that summer of pandemic, fires, Black Lives Matter protests. There's a lot going on and there are conversations happening and you're trying to change the subject to shield your daughter. And your mom says, “The world is full of suffering. She might as well know.” And I think it's in that same section that you talk about how you don't tell her about the dead bunny in the garden. It strikes me that the book is, among many other things, a gorgeous exploration of the way that suffering is intertwined with beauty and I'm wondering how we talk to our children about that. It feels like something that you grapple with in the book.

You know, Callie didn't find out about that bunny until we got the hardcover of the book, and it has a map, and it says RIP Bunny, and she's like, ‘What's this about?’ I had to tell her about the bunny.

So now she knows.

Now she knows about the bunny. She does not know the whole death of the bunny situation but she knows that there was a dead bunny. I don't know, you're right. I am still grappling with it. One of the things is kids keep getting older, and so that's a beauty. As they mature, their ability to process information increases. I was on Instagram this morning and I was reading this thread about a guy who was trying to get his three-year-old to sleep, and so thought he'd recount the most boring story that he could, which was all about particle physics, which the father happened to know a lot about. And then the son becomes deeply, deeply interested in atoms and atomic matter, and that everything is made of atoms, and this is night after night after night. And now, during the days, the kid's fascinated by particle physics, which feels like, and was for the father, ‘this is too big for this three-year-old to understand,’ but in a way, everything is too big for a three-year-old to understand. So if you figure out how to share things with small people in compassionate, instructive, patient, caring ways, anything is graspable. Anything is graspable, and I benefit, I think, with my daughter, from just assuming she is a deeply intelligent human, and trusting that we can talk about big subjects. Also, she is at risk, so not telling her about racialized police violence, not telling her about the erasures and dismissals and diminishments of women, not telling her about the realities of American history as interrelated with indigenous American history, doesn't make it go away, and doesn't stop her from being impacted by the damages caused by all of those things. So she might as well know so that she can be prepared to absorb those impacts in ways that are not as damaging to her.

Right, that makes sense and it also reminds me of another part of the book that I loved, and that also disturbed me. You talk about the revision of the Oxford Junior Dictionary and how words like “wren,” and “heron,” and “beaver,” and “blackberry” are replaced with “blog,” and “celebrity,” and “voicemail,” and “endangered,” which is almost too on the nose. It was kind of the only part of the book that made me feel a little bit hopeless because language and how we understand it shapes our world, to a large degree.

Maybe we just keep using the words in protest of the disappearances. I don't know. I don't have a full answer. It is very scary.

Right, just expand the vocabulary, I guess, which brings me to a different kind of expansion. I want to ask about the mechanics of getting this book out into the world, the publishing journey. Because, as you note, there is that popular conception of nature writing and your book pushes back on it. Was it a hard sell to a major publishing house? I know that this was one of the first books that Yahdon acquired. Was it at all difficult for him to champion the book?

No, no, it wasn't hard for him to champion the book. I had published Guidebook to Relative Strangers with Norton, which was great, and they helped create a lovely book. And they then had first rights for Soil, and they were fine with it, but I was a little worried about how it would be handled there. Yahdon has so much energy and so much vision, and it was really exciting to think about working with a black editor who pushed back at me and kept challenging me in a lot of ways that were really, really important to keep me honest, to keep me unapologetic, to keep me saying what I needed to be saying. And so, that just ended up feeling to me like the book would be best served with that editorial relationship that I was going to get with him. And this is a very different book, this is not the book that Norton saw, and so the book that Norton saw, I could actually see why they were like, ‘I mean, okay, we can do that.’

How did it change?

Well, for one thing, it is a book-length narrative now, as opposed to- it was just much more choppy. All that time stuff that we talked about had not been worked out yet. That version still had a lot of time zone problems and it was not particularly easy to read. In fact, my father read that version and he said, ‘I mean, I read it because I love you.’ That’s the other reason I don't want it to sound like that this was Norton's fault. Norton got the book that they got and they responded to it actually, probably, quite within bounds completely for the book that they received. It was going to be much more of a kind of academic kind of text and niche, and then in my long, long, grueling time with- I think Yahdon and I figured out that he and I went through five revisions of this book from the time Simon & Schuster acquired it to what you have now. And I had already done three or four on my own, so this book is chiseled now. One of the revisions that happened with Yahdon is it blew up to 105,000 words, and then over a period of not many months, I had to take it down to the 82,000 that it is.

That is a big job. And, to get back to our time question, that's not really the kind of work, you can do in 20 minutes increments, right?

No, no, no. Callie was back in school by then.

And were you back to teaching?

Yeah, how did I do it? I think I was only teaching one class. But I was also writing the podcast. I don't know. I mean, that was hard. I don't really remember that year. You know what I mean?

You blocked it out.

Was it '21 or '22? I don't know. But I know I was only teaching one class, and so that did help.

Revision feels like the kind of thing you need stretches of time for, to really focus.

Yeah, I did. I needed pretty big chunks of time, but it must have been '22 and so she was actually in in-person school again by then.

So the revision was sponsored in part by in-person classes.

By American public education.

Are you working on anything new now? Or are you taking this time to just be in the publication process?

Well, it's not really either of those. I'm not really working on anything new. I'm always writing poems, and that's part of why poems show up in Soil. Usually what would happen would be I would be writing poems and then I would publish a book of prose and then I would publish the poems separately. But these are all of a piece.

Yeah, I love that there were poems in this book. I love when different genres and forms can be friends.

But I am hoping to finish a new book of poems. It would be great to not have 10 years between books of poems, so I would like to finish that. But because Yahdon and Simon & Schuster are doing such a fantastic job of spreading the word about Soil, I'm doing a lot of interviews and I'm writing copy. Social media is this whole other thing that John Muir didn't have to think about. I should have added that to the list of things that John Muir didn't have to think about.

When you don't have to wash your own clothes or feed yourself, or repost other people's stories, you can get a lot done and spend a lot of time in nature. It seems like it’s another full-time job to just spread the word about the book you spent all that time writing.

Yeah, and this is how information is conveyed now, and I'm so grateful that since technology aligned with our big virtual shift of 2020, we have this way of meeting and talking to each other.

Yeah, for sure. This newsletter wouldn’t exist without it, I don’t think. It was very much a 2020 project. I know it's grueling for authors, but I love all of the events, the interviews. When you love a book, it's so fun to hear the author talk about it and spend more time with it in this other way.

Yeah, and I find it really funny now that I've written this whole book about the very essential joy of being rooted and staying in one place, and now I'm about to be completely uprooted in order to share it with people.

Order your copy of this gorgeous book for the gardener in your life, and also everyone else, here.