"My Whole Career is Totally Different and It's Definitely Because I Became a Mother"

A Conversation with Angela Garbes

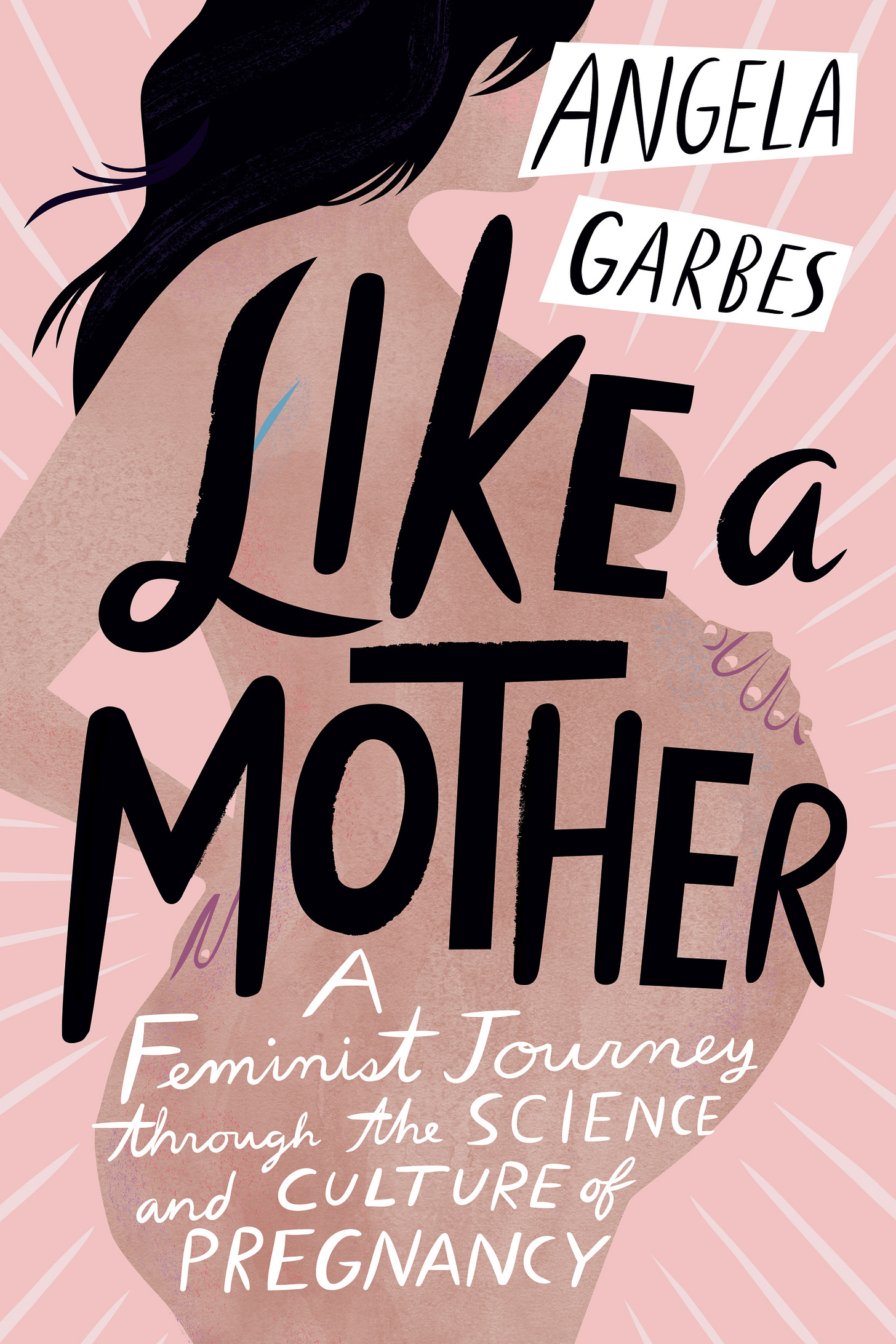

I am that annoying person who, if you tell me that you are pregnant for the first time (and sometimes even for the second or third time), I will send you a book. Not What to Expect or Ina May but Like a Mother: A Feminist Journey Through the Science and Culture of Pregnancy by Angela Garbes. Like all great gift givers, I preempt the delivery of the book with a disclaimer. “Here's something that might scare you a little bit,” I write, “but it is actually amazing and you need to read it.” The book is unlike any other pregnancy explainer, not just because it goes beyond pregnancy to the postpartum period but also because, unlike other books that attempt to shed light on the crazy process by which new humans are made, the focus is not just on the growing person inside but on the growing person on the outside as well. In a world where we tend to focus on potential risks to the fetus (what risk does COVID vaccine carry for my baby/chances of conception?) rather than risks to the mother carrying it (what risk does COVID carry for me?), Like a Mother looks at pregnancy by centering the maternal body which, after all, is a baseline requirement for the whole enterprise. The book strikes a refreshing balance between emerging science on pregnancy and the voices and experiences of people who have gone through it. It offers a way of looking at birthing bodies that shouldn’t feel radical but does.

In our conversation, Garbes argues against my gifting disclaimer: she is insistent that what we perceive as scary is what gives us power. And so much of her work is about confronting what we have been raised to fear or to accept without question so that we can move through the world with more power and agency. Like a Mother is not a brand new book, it was published in 2017, but Garbes’ work on women, bodies, and culture continues. Last month she published an essay in The Cut on what women have lost during the pandemic and she is also at work on a book that attempts to do what Like a Mother does for pregnancy for a wider range of bodily functions and experiences. Garbes is a writer with a talent for writing about what it means to move through the world and write with a maternal body, and a human body, and so I offer this interview as a gift to myself and to all of you in this challenging time when so many of us are struggling with giving our children what they need while also preserving our own creative drive (not to mention our sanity). Enjoy!

A few weeks ago you published an essay in The Cut about the impact of the pandemic on your work as a writer. It gave voice and urgency to something a lot of women are dealing with and feeling right now. You have two small children - are they in school at all? How did you get that piece done?

It helps to have a deadline. I still have a deadline for the book that I'm working on but I've found that it's difficult to do deep, creative work on a long-term project so the book has been like an anxiety cloud that hovers above me. There have been stages of the pandemic and we were alone 24/7, no child care, for four months straight. That was the hardest part and after three weeks, I knew there was no way I was going to finish the book. So that's when I moved the expectation of the book not happening in July, but if I got it done by the end of the year, things wouldn't be too thrown off. And then there were the freeing summer months. They went back to preschool and daycare in the same place. I haven't been inside their school, the protocols are very tight. But that was a moment where I was like, 'I'm going to be able to write again.' And now I almost feel like I blew that because it turned out I couldn't, still, and there were these two months that they were blissfully in daycare and I don't know what I did during that time. I know I worked, I did some freelance stuff, but I still couldn't engage. I wasn't mentally in that place and I struggled with feeling bad, like I was failing. You know, I finally have child care again and I can't get myself to write and that's bad. My oldest daughter is now in kindergarten and kindergarten is entirely online. I think I was holding out this hope that I would be able to settle back into writing in the fall because that was the mindset that I had in the spring, that schools would be open in the fall. There's just no bottom. Lydia Kiesling wrote this great thing, the last Letter of Recommendation, that felt so familiar where she was like, ‘you'll get to see your friends soon,’ ‘There will be kindergarten in the fall,’ ‘maybe things will be back to normal.’ It's been this shifting of goal posts. And so now my daughter is here, doing virtual school every day.

That's very hands-on.

It's very hands-on. I mean, she's a kindergartner, she can't tell time. When she is on a break, she's fairly independent and I've been getting her more independent, but she looks for us, she looks for someone to talk to, hang out with. She can't make herself lunch. So my husband and I, in our best attempts to give each other hours as opposed to minutes to work, exchange whole days, so we each get two and a half days a week.

And this is your first experience writing a book with two kids.

Yes, my first experience writing a book with two kids. After my first daughter was born in 2014, I was working full time and we had nanny shares and my mom and that kind of thing. And then when I was writing the book, my husband and I were both working from home because he was doing consulting work for the UAW so we were splitting days and then we were like, this doesn't work, so when she was close to three or two-and-a-half we got her into a daycare center. And then she was in childcare and that was critical to me finishing the first book. I finished the book at the end of the fall of 2017 and then didn't have a job to go to and I gave birth in March of 2018 and the book came out in May. I haven't been going to an office since August of 2016. And I should say that the only reason why anything gets done at all is because my two-year-old is in daycare now and has been since July. No one would be doing anything if she was here.

And you're both working from home, in the house.

I was working in our guest room, which has always been my office because he's mostly gone to an office and then he was working in a garage for the summer but it's uninsulated so he moved inside and then he was working from our bedroom, which no one really wants to do. So we finally just took the bedroom out of our guest bedroom because we're like, ‘no one's coming to visit us.’ And we're just moving all the time, moving laptops. Today is actually his day to work. There's just so much logistics. This is the world's most boring interview.

No, this is the stuff that I love because I think what's missing from the conversation a lot, even in the most normal of times, is how does this kind of work, the deep-thinking work that you talked about that's a little elusive right now, how does that get done when your life is not a deep-thinking life?

It's so hard to get into a deep thing when you have to spend, you know, 10 minutes arranging your workspace to begin with. My husband has always been ‘your work is equally important to mine, take the time that you need’ and it's really been me that's struggled. In the earlier part of the pandemic, I was like, I'm not making any money., it makes so much more sense for me to take care of the kids. We don't get health insurance through my job. So I took a lot of that on and he was really like ‘no, no, no, we're going to split this evenly as possible.’ And it's really only been maybe since November that I've been able to really say, ‘no I'm shutting the door, I won't pop out if I hear someone crying.’ My therapist said, ‘maybe you need a sign that says Mama is Working, and maybe you just need it for yourself.’ It's been a psychological change for me, a boundary-drawing that I wasn't capable of earlier in the pandemic.

But it's the only way.

It's the only way now and it's also just realizing that this isn't some rough period in my daughters’ childhood, this isn't some rough period in my life, this is my life right now. And I think that there's some acceptance in that that makes it possible for me to work better. To get that Cut piece done- I had been in conversations with my editor, she commissioned that piece back in November, but then they delayed it until February so I was given a reprieve. And then all of a sudden, I had a week to write the thing. I had been mulling it over for a long time, which is great, and it's everything that I've been thinking about for so long, I felt really excited to do it. But we had decided to go away for the weekend and we were in a cabin but didn't have any internet and I was supposed to have the draft in first thing Monday morning. In a way it was good, I had no distractions. My husband took the girls out on Saturday afternoon and I just hid in a room and I turned in a draft and a prose that was not as clean as I normally would and it was 3,300 words and the essay that ran was 1,200. I think I've had to let go of some standards that I held myself to before which maybe weren't the most healthy or helpful and mostly it's just a lot of negotiations and logistics. And, like I said, I feel like I have a really great partner in that sense but a lot of it is me making that space and claiming that space and drawing those boundaries. It's been really difficult.

That's something that I'm kind of obsessed with, pandemic aside, but it's definitely exacerbated by the pandemic. In your book you talk about how, even when you are firmly in the workforce, you are expected as a mother to sacrifice your body and your mind and I wonder to what degree some of us have set ourselves up for that. It's definitely not true across the board but I think a lot of mothers are in the situation that you described in your essay of having chosen more flexible work or less lucrative work because of what they wanted out of motherhood, or anticipated about it, so it kind of becomes this vicious cycle and I'm not sure how we break out of it.

I think that's probably true of a lot of people. I was a staff food writer at an alt weekly and then I got this book deal and I still liked my job so I asked if I could take a year-long leave of absence and they were like, ‘nope, we're not gonna hold a job for you, what are you talking about? We don't have to pay your health insurance, we'll just piece it out on contract, you're welcome to freelance for us.’ I had thought I would go back to that job and so when I published the book I didn't have any sense of what my career options were. And the book that I'm trying to write now, the vexing anxiety cloud, in retrospect, I think I sold it for all the wrong reasons. I totally am interested in the topic, I still want to write this book, but I sold it two months after my first book came out, four months after I gave birth to my second daughter, and it was a feeling of I didn't know what I was going to do and I didn't know how I could be a mother to two kids and have a full-time job and I also thought, I'm having a certain amount of success-

You have to capitalize on it.

I think other women of color do this too, it's this sort of scarcity mentality of it could go away at any time; I make one mistake, it's over. I just thought my opportunities were going to go away because we're also taught that opportunities go away after you have a child. And I found myself in this position where suddenly I actually had more opportunities after I had my child and motherhood opened up this whole other avenue for me. My whole career is totally different than I ever thought it would be and it's definitely because I became a mother and a lot of my writing is about that now. So I don't know that I set things up specifically for motherhood in this way but I think after I was out of an office for a while I was like, ‘I don't want to go back to an office.’ I was in a newsroom where I was one of three people of color and then one of two people of color. It wasn't great and it was media and it was really like ‘blog more’ and ‘do more with less.’

The opposite of the deep thinking that you probably wanted to do.

Yeah, and then I was like, oh I am straight-up not valued, you don't want to hold a place for me. I thought writers and voices and beat writers were your greatest asset as an alt weekly but okay. So to be able to be in a position potentially to call my own shots would be great. But – and this is pre-pandemic but now it's exacerbated – I always had some mixed feelings about being the freelance to the steady paycheck, the W9 to the W2 or whatever the tax form is, and having the health benefits come from my husband. I've had all of those feelings for a long time and I think it all gets pushed to the forefront then when you're pushed to a point of almost crisis.

It’s interesting to see how many writers feel like you do, that becoming a mother opened up new opportunities to write and be creative. I’ve found having children to be generative but what the pandemic is shown is that you can only make use of that creative spark if you don't have to spend all day with the children who are so inspirational, right?

Right, you need other things. It's great, children can inspire you or an idea but the children drain you. Creative work is different than an office job, it just is. It's taken me a while to realize that. It doesn't follow a schedule, it's a circuitous path, you're always kind of thinking about things, all of it is part of it. I miss going to readings, I miss seeing art. It feels like there's less time, less spaciousness, my sphere of inspiration feels like it's shrunk down. And I think there's something else that comes with kids that not just, ‘oh the children, they inspire you.’ I think having a child gave my voice some kind of urgency that I didn't have before. I don't know whether it’s hormones or it's the first time you're doing it and it's adrenaline and you've stepped into this other world that you know millions of women and people have done before and you're part of this tradition, but you have so many new thoughts. And I just was like, I have so much to say, I have so many ideas in my head, I have so many thoughts, I have so many questions about all of the systems, all of the things, about who I am. Why am I like this? Why do I want to parent like this? How was I parented? It just all felt like it was bubbling over. I think that there was an urgency that I didn't feel after my second child. Maybe I thought I might have it again and that's why I could write the second book in a similar manner. But it feels like it was a feverish kind of thing. And that was a real gift that my daughter gave me and I feel in touch with that in some ways. Talking about it now, I get excited. Could I get back to that? What other things could create that spark or something close to that?

I think one of the many reasons that I really appreciated your book was because it offered a kind of embodied feminism. Even in my feminist education, I don’t feel like I was encouraged to think about my body in that way. And I think there was a sense, when I was younger, that if you talked about biological difference, it would ruin the whole feminist enterprise. But then I had my first child and my husband is great and a very present, amazing parent but all of a sudden there was this sharp division in our roles and even just biochemically, there was something so different about my experience. How can we move from a feminism that says you can do anything to one that acknowledges this very real change or bodily experience?

I relate to what you're saying, I agree with what you're saying, but isn't that academia in general, where it's the triumph of the mind? And isn't it also western society and culture, where the body is a thing to be pushed down, tamed, defeated? It's messy, it's inconvenient, it's a liability. And your mind is the thing that is pure and clean, it's your essence. And the book I'm working on is about bodies so I've been thinking about this. Western religion does this. I grew up Catholic and the body is sinful and dirty, and the mind is what's pure, and the mind is attached to the soul, and the mind is what's noble. But I also think that you're right, in terms of feminism, we've been taught that for women to achieve, it's in spite of our bodies. We have kids but we don't let that stop us. We live in a patriarchal society and I think most feminism is still very Lean In feminism, let's succeed on the terms that men have set. There's not a lot of talking about let's consider matriarchy, let's consider other power structures. Let's work for a world where we are paying wages for domestic labor or a basic income.

Which was something you got to at the end of your essay.

Yes, there was more of that, which is something that I've been coming more and more into. There was an amazing op-ed piece in the New York Times a couple of weeks by Samantha Hunt, who's an amazing short-story writer and novelist, about how she's trying to talk to her teenage girls. We've seen them as ‘here comes trouble’ and why don't we talk about what female bodies do or how having emotions and caring for people, that's real power. She kind of compares America to a moody teenage girl. That's the conversation that I want to have, that embodied feminism. I think our society tries to control and oppress women because we're infinitely more powerful. They are dependent on us. Female reproductive parts, female bodies are what you need to continue life. And that's the ultimate power to continue to live and exist as a species. So yeah, I think we should be talking about all of those things so much more, we should be talking about bodies more, and how they're terrifying and beautiful and amazing. My parents are Filipino and they're very conservative and I got a talk about how sex was a beautiful gift that I would give one person. I didn't get a biology lesson. We just don't talk about stuff and we let silence stand in and we let cultural bullshit stand in. And so even women who are incredibly feminist and progressive-thinking- when my book came out, I was on Fresh Air with Terry Gross and I heard from so many people that throughout the interview she had been giving this sort of warning to the listeners where she was like, ‘we're having a very graphic conversation about childbirth and what could go wrong so if you have kids, just heads up.’ And she did it like three times and I was like, ‘Terry, I love you but can I just ask you about that? I get it, you want to give a heads-up for kids but I just think kids are closer to this than you think.’ And she was saying that when she was 12 someone told her how childbirth worked and she was like, ‘oh no, you've got to be kidding,’ and she said, ‘the truth is really horrifying.’ And I remember just being like ‘yeah, the truth is horrifying if it's been hidden from you your whole life.’ And it's not that I thought of her as the ultimate progressive-minded feminist, but she also asked me ‘do you think women should know about all of these things, things that could go wrong?’ And was like, ‘um, yes?’ I think that there's a generational divide and I think we're in a place where we can see that split more clearly and be part of undoing it. To me, it's not that weird to explain my period to my two-year-old in the same way that I explain that we have to keep cutting her nails because they keep growing.

Right, imagine if you only cut your kids' nails while they were sleeping because heaven forbid they know that they get longer. You could really turn anything about bodies into this horrifying thing. Bodies are weird, or totally normal, depending on the lens you're looking through.

Yeah, giving birth, bearing children, being pregnant, having a period even if you never decide to have a child, this is what your body is designed to do. It's arguably the most essential human biological process – why don't we just talk about it like that?

And maybe teenage girls wouldn't be so horrified when it happened to them.

You wouldn't be so scared of it. I think it's already kind of how I live but this idea of embodied feminism, you can talk and talk and talk but that's the same thing where it's all brain and not learning about our bodies, not moving our bodies and taking up space with our bodies, our inconvenient, beautiful, expanding bodies.

So, speaking of bodies, tell me a little bit about your new book. I know it's a bit of a sore subject in terms of finding time to work on it but I'm excited for whenever it does make its way into the world.

Yeah, I'm excited for it, too, it's just been really hard for me to do it. With the first book, it felt like there were very neat walls to contain the subject and then when you're writing about the body, it's related to everything. But it starts from the same place. I didn't know about pregnancy until it happened to me and then I thought there's so many things in our bodies- I don't think very many people know what their gallbladder does unless they have to get it taken out. A lot of how I see the book is pushing this agenda of appreciation for your body and what it does. And I wanted to mix personal narrative with some reporting and research and learn about these basic body processes and write about subjects that I'm interested in. I'm writing about parenting as physical labor, that kind of thing. It's all the stuff that I've been thinking about and wanting to write about and placing the body as the primary lens. There's a lot of research that's been done, there are many outlines, there are many shitty drafts of chapters. I do feel that, whenever I can get to that place, it will come together more quickly than I think. The process has just been so much harder than I thought. And I'm in a good place with it now. Before I had a lot of guilt and shame about it.

Half the work is getting over those feelings, usually, but it's harder to move through that difficult stage when you don't have as much time to devote to it, which compounds the guilt and the shame.

It was a big breakthrough, it's only really in the last few months that I've been like, oh right, I'm a writer, I'm an artist, and being productive doesn't work in the same way. And because I've monetized my love and my art, I kind of have to on some level but I think I've internalized that more than I need to. It hasn't felt fun or creative in a while, it's felt like ‘I have got two hours to try and be smart on the page’ and it's just doesn't work that way here.

You can't force it, you really have to take it when it comes but then again, you can't always take it when it comes because that's your day to work in your bed or someone's coming in because they need a sandwich.

I think I'm in a good place right now because I published the piece last week and the reception and feedback to it has been surreal. So that's been really good.

I keep thinking about that line from the essay: "What is my work? I continue to call myself a writer though. I do very little writing." I talk about this all the time, I've talked about it in interviews with other writers, where it feels to me like it's the only profession where you will stop feeling that you belong in it if enough time has elapsed since you've produced something or had something published. It's not like you write a book and then you can call yourself a writer, you have to keep renewing it?

Yeah but I mean if I were to think about it, I've thought of myself as a writer secretly since I was like 12 and I've always been a writer and I'm always going to be a writer even if I end up doing something else and that's a new place that I'm trying to be in.

And I believe that on a spiritual level but if it's been an insane year and I really haven't published much then I think I'm kind of a writer? I'm a writer and I used to write a lot more?

Yeah, but I also think that's part of our culture, too. Once you do something, you're supposed to do more. I think about teenage me who would be like 'you got to write a book? That's the dream.'

But isn’t the rule that if you publish a book, you get to call yourself a writer forever?

But how do you break out of this trap of, I published a book but I have to publish another one that pushes boundaries in a new way for me to continue calling myself that? I just keep moving the goalposts on myself. That feels like my lifelong work, figuring out how to maintain myself, just me, not writer me. Being a writer, being a mother, I think that's a life's work and instead of beating myself up about it, I'm trying to be generous with myself and realize it's probably going to be stuff that I'm struggling with or sorting through for the rest of my life, hopefully.

Something that stuck with me from your book was how, with new mothers, we tend to pathologize the difficult emotions or gloss over them, pretend that they don't exist, if they say anything other than ‘this is the most magical amazing thing I've done in my life’ and it seems like we're kind of seeing another iteration of that in this backlash against mothers saying they're at a breaking point where, in the comments sections, you have people saying, ‘well if you didn't want to spend time with your children, you shouldn't have had them.’ That whole, moms are just complaining about this thing that they chose to do.

Children require more than one grown-up, children require more than two grown-ups. Pathologizing those difficult feelings, if we apply it to the current moment, if we reduce it to, ‘oh you're just complaining and your kids deserve better than an angry mom who resents them,’ not ‘why don't we take this storm of emotion, which is very legitimate and very powerful, why can't we see that as an opportunity to take imagination, which I know we all feel is in short supply these days, and think about what could we do to not make it this way?’ How could we take this time and see these emotions and see that people are saying ‘I am breaking down, I am not going to make it, I do not feel like I can do this,’ and why don't we ask the question, how could we make it so that people could continue? And then we could perhaps imagine a better society that values women and work and care. When we shy away from those difficult emotions, we shy away from the opportunity for growth, and that's personal and on a cultural level.

That's probably why we pathologize them. It's easier and preferable to say, ‘oh, the moms are having a hard time, they've made their bed,’ rather than think maybe we should restructure things. I think this pandemic has just laid bare what always existed and allowed us to see what we’ve been missing out on because care work is not monetized.

There was a whole section in the original draft of The Cut piece that was you know, trying to say what we lose when we don't have women in the workforce or when moms just kind of vanish into domestic life. We lose art of all kinds but we're also losing research, policy ideas, and in that sense, we're losing all of the things that got us in here in the first place. The tipping point for me where I was like, ‘I'm gonna vote for Hillary Clinton’ is because I read that when she was working at a law firm, she wrote her own maternity leave policy because up until that time they had never had a woman return to work. So I was like, ‘okay, this is what we need, someone who, built into their perspective, is thinking about family leave on some level.’ Or, I never get tired of Elizabeth Warren telling that story about how ‘Aunt Bee showed up and stayed for 18 years and took care of my kids.’ I was weeping when she was at the DNC saying childcare is infrastructure. That's what we've been lacking in the first place, that perspective built into our institutions. Tammy Duckworth was the first seated senator to give birth and she came and brought the newborn to vote and I was like, ‘this is amazing.’ And then I remember also thinking at the same time ‘she deserves more than 10 days leave.’ Mothers' inability to work, whatever that looks like, or do anything besides domestic work, really limits their participation in public life. And in terms of public and civic life we can see what the problem of not having the perspective of mothers is, it's modern American life.

Can we find hope anywhere?

I think about how hope is non-negotiable. Hope is a practice. There are people who have never had the ability to give up on hope, it's an issue of survival. In the same week that I published that essay and New York Magazine ran a cover story on women and work and we had a whole weeklong package on The Cut, the New York Times came out with a massive multimedia thing. And the week before that there was the New York Times full page ad talking about the Marshall Plan for Moms, we should be paying mothers $2,400 a month. Change is so incremental and slow and it's frustrating to me to occupy the space where I think, what do I do? I helped change the conversation. But we need everyone at every level. So I have this hope because I think there are more people talking about these things. There are more people who want to talk about, what are these difficult feelings, why do we shy away from those things? So I think there's that and I think it makes a difference. It's ten years of screaming that result in a small policy change. And, of all things, the thing that gives me hope is that I saw that Mitt Romney introduced a plan where he's talking about how, if you have children under the age of five, you should be getting $350 a month per child and $250 for kids up to 17 or something. So, I mean, I think he wants to get there by slashing welfare programs, but it's a version of basic income.

And it has entered the conversation, if Mitt Romney is talking about it...

Yeah, so I find that hopeful, I think something has happened where we're starting to have that conversation. And there's people who are always doing this work, who have always been doing this work. There's been a movement for wages for domestic labor for years. It's really easy to despair and I think that's for everyone. I'm on antidepressants now, so partly how I'm able to have any hope for the future is directly related to resources that I have recently availed myself of. I think that's real, that feeling of, is there anything to look forward to? Everyone has those moments and so I think it's really important to dip back into that and reframe it because I have to do it for myself all the time.

Do you find that the antidepressants have helped your productivity?

Not dramatically, I haven't seen a miracle. But in the sense that it helps me, it helps me maintain faith. I can stay in it more. I can show up and write. I think The Cut piece wouldn't have happened if I was not on antidepressants because there's just an ability to stay in the work with the faith that one day it will work. Like I said to you, I think that when I find whatever momentum it is to finish the second book, I think that it will come easier than I thought, I never would have thought that five months ago. And it's not, ‘I'm definitely going to get it done.’ I still don't think I'm going to meet my new deadline of July, but I have this feeling of, if I keep showing up, it might work out. Or, it feels useful to show up, it feels useful and right to be doing this and it's easier to maintain faith and belief in my abilities is what I would say has been the change for me. This is another one of those things where I'm like, ‘I'm just going to talk openly about everything that I can.’

***

You, too, can give the gift of information and power by ordering Angela’s book for yourself and/or loved ones here.

I am a big fan of Angela Garbes and everything she writes - thank you for this powerful interview!