"You Get to a Certain Age and Most of the Memoirs You’re Reading Are Not Really About You"

A Conversation with Gina Frangello

Back in the halcyon days of 2019, I wrote a series on antiheroes for Longreads, the premise of which was that so-called prestige television had found a way to portray a protagonist who did bad things such that viewers would sympathize and even root for that character, even as his behavior became increasingly less tolerable. I say “his” because those shows – The Sopranos, Mad Men, Breaking Bad are the most famous and obvious examples of the genre – mostly featured male protagonists. And those bad men we rooted for always had a female foil, usually a wife, who threatened to stand in the way of their self-actualization. We, the viewers, didn’t like that and we didn’t like those wives. So one of the aims of the Longreads series was to think critically about that dynamic and why it endures, as well as to consider whether a television show might be able to do the same thing for a woman: make her a character we root for despite what we might otherwise consider bad or harmful behavior.

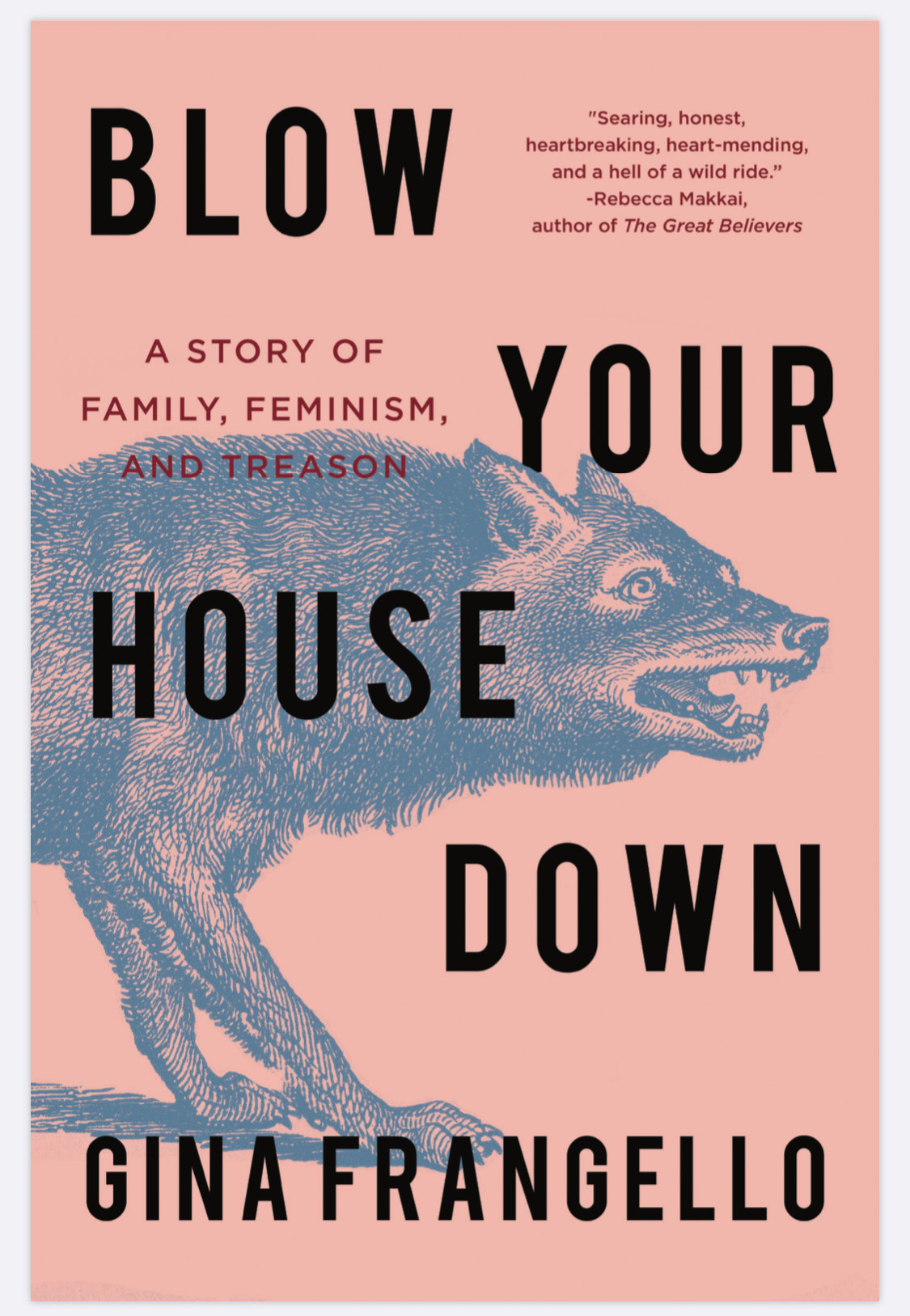

This is all to say that I couldn’t help but think of all of those antiheroes as I read Gina Frangello’s Blow Your House Down: A Story of Family, Feminism, and Treason. Frangello is the nonfiction editor for the LA Review of Books and has written a number of novels and nonfiction essays over the course of her career. In this gut-punch of a memoir, she paints a nuanced picture of the years in which she was living a double life: raising her children and caring for her aging parents while having an affair with a fellow writer. Frangello is unsparing in her portrayal and analysis of her own behavior and the way it impacted those closest to her but she pairs that self-critical lens with sharp cultural analysis that asks us to consider how our existing societal and artistic narratives might shape the judgment we feel moved to render when we read about her mistakes. The book is a challenging and necessary read, especially given the messages we’ve internalized about motherhood and what we are expected to give up when we join its ranks. As I read it I couldn’t help but think: here, finally, is a nuanced portrayal of a woman who has done something we as a society have decided is wrong but something for which we have forgiven many, many men, both fictional and real. How do we read this person? What do we take away from her story and how might it change the way we write and think about women, in real life and in fiction?

So I guess what I’m saying is, someone needs to option this book ASAP and the rest of us need to get reading. It was an absolute pleasure to talk about “unlikable women,” Frangello’s rules for writing about her children, and why we need more memoirs about middle-aged women going off the rails.

Talk to me about deciding to write this book because you’re a novelist and Blow Your House Down is a very intimate and searching portrayal of your own life and the lives of your close family members. Was it a difficult decision to write the book?

I've written a lot of nonfiction, personal essays for over 20 years but I didn't really think that I was going to write a memoir. I did sometimes bat around the idea of writing an essay collection primarily focused on my parents and caregiving my parents and had published a lot of pieces about them. But as I was going through some of the things that I was going through in the book, I found that I couldn't enter a fictional space the way I normally can. Usually I can so obsessively that it's all I can think about and the characters become almost more real than a lot of people in the real world and you're having dialogue coming in your head while you're driving your car and all of those things. And it was just sort of dead, it was dried up. And so I was writing these essays on my own and not really showing them to anyone and then it finally really dawned on me that it was all part of the same story, that the caregiving of my parents was not its own story in which I was the sort of detached peripheral narrator and that to even tell the real story of my relationship with my parents I needed to be more honest about where I had been coming from at the time. And it really became increasingly exciting as I was going along when I realized that I had an opportunity to talk about more than just myself, that I had a chance to talk about a lot of things that have been obsessions of mine in terms of women's roles in society and culture throughout history, things that I read about obsessively and that I've studied in graduate school and that I bring elements of to my fiction writing but in a different way because you can't suddenly just go off on a tangent talking about the female malady or something like that. So it started to occur to me that I was actually able to write in an attempt to communicate directly with other women and I guess be of some help, hopefully, through the experiences that I had had. And I feel like now that I'm done with it, I'm very ready to return to fiction.

It worked, you unlocked it. All you had to do was write a whole other book. You had to write very candidly about your family for this book. Did you have any rules for yourself when you were writing this book in terms of what you would include and what you wouldn't? How do you stay sensitive to your children's current and future emotional needs while also telling the story that you need to tell, and that you think other people might need to read?

That really is such a good question because that's a wide spectrum in terms of how people write today. Since the beginning of blogging you would have people who were basically divulging every single detail of their children's lives in a blog or who would write a memoir specifically about their child's special needs.

Yeah, now you see it on Instagram. It's a different genre obviously.

Right, my daughters are adults now, they are almost 21 and in that case I was able to get adult consent. My youngest just turned 15 and plays a much more minor role in the text than my daughters. It's certainly not because my youngest child is less present in my life but because I really did try to minimize the role of a minor as much as humanly possible without writing it out of the story entirely. But I do have certain rules about it, for sure. I try not to really talk about anything regarding my children that doesn't have directly to do with an interaction that in some way I caused. I do write about things like my daughters and I took a service trip to Guatemala during a difficult period of our lives where I was just kind of beginning my divorce process, I talk about the fact that my daughters busted me when I was first having my affair. I am culpable in all these things; my daughters did nothing wrong. And so I try never to really include details from their own personal lives that don't have to do with me. It’s not even that I try not to, I just don't because it's not pertinent to the story.

One of the major themes of the book is: where is that that point of balance of doing what you what you need to do for your own life, for your mental health, for your own personal happiness and fulfillment in life, versus what you take on when you become a mother. How much do you have to give up of and for yourself when you become a parent? And I see that playing out on a minor level in terms of just the writing: how much of your story is you and how much of it overlaps with them? And what does that mean for what you can write. Do you think men just don't write as much about their kids or do they and they don’t have this conflict?

Some do now, right? It’s interesting, I'm not an authority on things like parenting blogs but I do find that if men write about their children, it's usually presumed that that’s somehow laudable and heroic because they're taking an interest in their children and they're being involved fathers. And I have not as much tended to see them being interrogated about what is your story? What is the children's story? Should you be writing this? I do think that there is an issue of men tending to be congratulated for things that would just be expected in a mother, which was that you would be involved in your child's life and that your child would be a point of interest to you.

Yes, even just like men traveling alone with their children, people are like ‘what a dad.”

Exactly, people are cooing as if they've seen a cute puppy. I'm sure that there are fathers who have come under fire for things they've written about their children but I do think that different standards tend to be applied towards moms versus dads. Even as a fiction writer, I was often asked about my children in interviews. I was often asked ‘what will you say to your children about this book?’ if I wrote a novel that included a sex scene or something like that. And I will legit say that in the in the realm of fiction, I have never heard a man asked that question. Obviously when you're writing a family-oriented memoir, I'm sure they do get some of that too. But a fiction writer having to explain the reactions of her family, I don't think that really happens to men. So it's all very interesting and kind of complex but I didn't want to use that as an excuse to go too far in some sort of reactionary, ‘well a man wouldn't get in trouble for doing this, so I'm going to just go to town.’ I still really tried to keep a lot of boundaries around my kids and definitely to get the consent of my daughters and to ask them at various points if they wanted to read and nix anything. And they didn't, they were just like, ‘write what you want to write, it's your story.’

I think a lot about what people call “unlikable women,” which is often just a way to describe women who don't make the kinds of decisions that we think women should make or behave the way we think they should. Throughout the book you make a point of anticipating the judgment a reader is going to have about a wife and a mother who blows her own house down and you never let yourself off the hook. But you're also intent on discovering the ways we as a culture don't let women off the hook where we do extend our sympathies to men in virtually the same situation. Just rhetorically, that's a really difficult thing to do.

On the one hand, I'm not a big fan of the inspirational female protagonist. Many great books have been written about them but not my books. Women in my books tend to sometimes make bad decisions, sometimes be difficult, and I've been drawn to essentially reading about people who are in some way in battle with themselves or with cultural expectations and who mess up. I'm not as interested in reading about situations where the tornado blows down the house and therefore everyone has a problem. It's much more interesting if someone in the house blows down the house and therefore we have a problem. And in nonfiction, we're always giving a partial representation, we're always giving a very curated version. It felt like the curated version that I felt an urgency to present was essentially one in which I was more than willing to look as harshly at myself, or more harshly at myself, as I was anyone else. In fiction you want to avoid the beloved character syndrome where you've got the character who can never do any wrong and everyone else is always doing that character wrong and that is how the conflict arises. And that character’s always innocent and you're always rooting for that character at all moments. Those don't tend to be the kinds of books I read in fiction and they don't tend to be the types of memoirs that I love so I realized that, if I was going to do this, I had to be pretty ruthless in terms of interrogating myself as a character.

As I was reading your book, I kept engaging in this thought experiment where I would imagine you as a protagonist in a Mad Men-type show because that is our cultural mechanism for excusing things like adultery. Those portrayals, mostly of men, are perfectly calibrated to keep you rooting for them even when they do bad things but that kind of calibration is rarely applied to women. One of the points that you make in this book is that we're all a mix of good and bad and that pretending otherwise harms everyone but you also note that all the great adulteresses of fiction end up dead from suicide. We have this cultural mold of what happens to a woman who “misbehaves” in this way.

It’s really interesting because in terms of television dramas centered on problematic men, the Don Drapers, the Tony Sopranos, the Walter Whites, somehow we culturally are willing to basically love these characters and root for them even when their behavior is so over-the-top it's literally insane, right? I mean we've got Tony Soprano ultimately murdering his own nephew. Not only is he a killer in the mob but he kills his own family members. Don Draper is married to a woman who doesn't know his identity and then basically just is a serial philanderer and not particularly involved as a dad and all of these things and yet we keep thinking, ‘oh Don will find love.’

Or, like, his childhood, you can understand why he does these things. That’s what I mean by that calibration.

Right, right. There's a there's a moment in my book where I talk about the fact that sometimes we as women have internalized that opening our legs at the wrong time is the worst crime in humanity. And that we will set it up against genocides and murders and pedophilia and so forth and feel as though somehow there's this moral equivalency. Like if you had one infidelity or something, that you've become monstrous, in that league of monster. There's a section early about a friend of mine who had written a novel about a woman who gets a scary medical diagnosis and starts sleeping with one of her female students and how when I was in a Q&A with her, I was leading the discussion, and all the people in the audience just wanted to focus on how absolutely horrible her behavior had been. One person suggested that the novel might be satire because for a sick woman to carry on this way- and yet, at the same time, the audience was basically fully acknowledging that had it been a man, there wouldn't even really be a novel because that was written about so long ago and so often that it wouldn’t even be noteworthy. So that dichotomy, how you can be doing something that is wrong but is it really on the scale of some of these other things that we feel sympathy for male characters for? I still struggle with guilt all the time about many of the things that happened in the book. And yet I also in some ways struggle with how deeply internalized that guilt is. And when is it all right for a woman to forgive herself and move on? I think these are questions that many men have an internal moral compass and ask them of themselves, but I think we as a culture ask much less of men.

Yeah, I think it's easier to forgive yourself when that forgiveness is culturally available as opposed to how it is most of the time for women. Talk to me about the different structures that you use to tell the story because I love that the book starts off addressing the reader in the second person and you have this play on the children's lit convention of A is for apple where you go through different A words: adulterous and author and artifice, atonement. But then you have more traditionally structured memoir chapters and some that are mix of structure and fragments. How did you decide what you needed structure-wise to tell the story?

A few of the pieces are revisions of pieces that were published in earlier forums. Those tended to be the more traditional pieces that I had to come at with a new lens because I was a more peripheral narrator of some of those essays. Those ended up being really cracked open and often re-formed. In terms of the pieces that are very structurally different, “The Story of A” was one of the last pieces that I wrote and it was based on notes that I'd taken. My husband, when he was writing his memoir, used to tell me that the notes are the book and I had all these notes of these different terms and I got this idea of what if they were all the A terms because there were a freakish number of them. And I always intended to do the dictionary of mutually understood words. I'm a Kundera freak and that's based on the short dictionary of misunderstood words between Sabina and Franz in Unbearable Lightness of Being. I think that the inside language or set of understandings within any relationship is a fascinating thing: what words mean, what frameworks mean in between two people, and how that changes over time and how it shifts and how words are slippery. There’s a quote that I always have loved, and I heard Pam Houston say it once but I don't know if she was quoting someone else, that the second person is a first person who's feeling bad about themselves or guilty. And so I liked the idea – and I've done it before in short fiction but never in a memoir – of trying at times to step back and look at myself as a “you” or a “she,” to figure out, how do I look from far away? How do I look from closer up? And each time that I work in second person, I end up coming back to the first person because ownership and accountability are really important subjects in the book. I think for nonfiction in particular I'm really interested in using form that kind of mimics the way we think and that's not always linear storytelling, it’s not always first this happened, then this happened. Our minds are always working in weird circles and in these kinds of tangents and I tried to capture that more in this book than I have in more straight narrative in my fiction, which isn't always super formally traditional but has not been as formally all over the place as this book has.

In addition to this being an adultery memoir and a story of feminist self-actualization, it’s also a sandwich generation story, which is so beautifully captured – I know it wasn't beautiful at the time but the descriptions of your parents living downstairs and your children living upstairs and you going back and forth between them, so poignant.

It was amazing for many years. My parents moved in in 1999, which was the year that my ex and I had bought the house. And my parents lived with me throughout the entire raising of my children. The girls were adopted in 2001 and then my youngest was born in 2006. So my parents were there for every step of that and in the beginning my mom was still fairly healthy and she was really a co-parent with me. She was with the kids and with me all the time. She came to Italy, she came to the park, she came to Chuck E. Cheese, she came to the doctor appointment. She was always there and it was wonderful. I had lived outside of Chicago for eight years at one point and then on and off for another couple of years when I was overseas and so it was wonderful to have that time with my mother. My mother and I were intensely, intensely close. And great to have that time with my father too and to be able to help assist in his care. But then there came a moment when it just kind of jumped the shark. My father was already very sick and disabled and had a lot of medical issues and a lot of mental health issues and then my mother had a heart attack and a stroke the same year that I had my youngest child and everything started to sort of steamroll, where it became really overwhelming. And that period lasted for about eight years before my dad got in-home care.

That’s a long time, with small children too.

Right, exactly. With an infant and two kids in kindergarten and then going from there. There was never a time where it seemed like it had been a bad decision to bring them there. It always seemed as though this would only be worse if they lived in Florida somehow or if they lived, 45 minutes across the city. My parents were in poverty their whole lives really and they didn't have the money and the resources to take care of themselves in that situation so had they not been there, they would have been in some kind of Medicaid nursing facility or something. My mother passed away in March of 2019 and I still think of having my parents living there as one of the best decisions in life because not only did it allow me to remain really close with them and to help them and allow my mom to have all those years to help me, but also, I think it really modeled for my kids something very similar to what I had grown up with in a really Italian American and Puerto Rican American neighborhood where family was very multi-generational and tended to live in the same house.

What so many of us are missing now.

Right, our whole block was basically made up of extended families when I was a kid. it was like, the sister lived in this building and the brother lived in the building next door and the mother lived upstairs from one of them. That was that was the whole neighborhood really and most of my friends don't live in situations like that at all. Many of my friends see their parents once or twice a year and that wouldn't have been a comfortable thing for me. It wasn't how I was raised.

I'm interested also in how that impacted you writing-wise because I would imagine in the beginning having your mother around was probably helpful. I'm always interested in how people with small children especially actually get the writing done. But then, it shifts where now not only are you taking care of small children, but you're also taking care of aging, sick parents.

My mom was a big help initially and my friend Kathy who died in the book was actually the first “nanny” that I ever had. She would come for 10 hours a week when I was working at the magazine that I edited then or when I was doing some of my own writing. So in Chicago I had a good support system and then by the time my youngest was old enough to be in childcare, it wasn't in my home anymore. We instead shifted to a daycare center, a woman in the neighborhood who we knew. The neighborhood that I lived in was very child-centric and family-centric so there were a lot of resources. And yet, writing time was and still is really scarce. During all those years, both during my first marriage and continuing since, I've always edited magazines, presses, online things like The Rumpus or The Nervous Breakdown. I'm now creative nonfiction editor at LA Review of Books; teaching, adjunct or being a visiting lecturer, doing developmental editing on the side. So even when I've had childcare, or now that my children obviously have long passed the age of needing childcare, there were always a lot of things pulling on my attention. And finding writing time continues to be a struggle having nothing to do with my kids anymore.

So what are the writing challenges now?

Well, during quarantine obviously, we had at one point six of us living in my house so of course it's hard to write when you are living in a house with five or six people in it. There's not a lot of space, there's not a lot of rooms with doors that close. I teach from my bed in Zoom because that's the room where I can close the door. My husband and I share an office and our desks are right across from each other and there's no door, it just leads straight to the stairway going downstairs. If you're teaching in there your voice is amplifying off ceiling and bouncing downstairs. And so certainly quarantine has made the demands of being in a family impact work much more again. But I would have a lot more writing time if I weren't so intent on my passion for editing. I love being part of the literary community in that way; I love being able to publish somebody and get their work into the world. It's always been part of my life even when it wasn't monetized. Now I focus also quite a bit on things that I need to do to earn money but I was always really busy, even when making money wasn't a concern so it’s just, I guess, my nature.

Yeah, I think that's true of a lot of creative people, that wanting to be getting their tentacles into all sorts of things. It's hard to resist.

I'm also a binge writer. I admire people who are like ‘I wake up at five o'clock in the morning every day and I write for two hours and then do the treadmill for an hour before my family wakes up,’ and I'm just like ‘well, I think I would probably just never move or write again if it relied on my having to do that.’ But thankfully that's just not the way my brain works anyway. I'm not always in a place where I'm writing. Often, I'm in a place where I'm reading other people's work voraciously and I'm reading published books and I'm reading student work and my mind is very consumed with those things. And then I'll start to just become obsessed with a certain new idea for a project and maybe I've been thinking about the project for three years but didn't start writing it, and then all of a sudden it just takes precedence. It's like I can't drive my car without hearing it unfolding in my head. And then you know it's time to write.

So is that hard to then get that time when you need it? Do you just take it from wherever you can? How does that work?

It used to be of course much harder when the kids were younger. I mean, even to the extent that I did have always child care and support of extended family. I never had anything like 40 hours a week of childcare or anything.

And there's also that pressure when you do have someone else watching your children.

Right, and sometimes I was in the home while it was happening and sometimes I had childcare because I was helping my parents with something. It’s certainly not as hard interpersonally as it used to be because my parents are unfortunately gone, my children are grown, but now there are different reasons. I work more for economic reasons than I used to and so those things take up my time. But I'm in academia, I have summers off and if you're a binge writer, you can do a lot of writing over the summer and you can do a lot of writing over winter break and you can do a lot of writing maybe one day of the week where you don't teach any classes and you've cleared your editing plate. So I'm not one of those, ‘you know, if I can get one good paragraph every day,’ it's more like ‘if I can get 11,000 words in one day then I may not write for the next three months.

In the book you quote your lover who said “the arc of mental illness does not conform to a redemption narrative,” which made me think about the place of the book among redemption narratives, particularly those I think of as blockbuster adultery memoirs like Eat Pray Love and Wild where these women have affairs and their marriages end but that's just the beginning of their story and the story is that they're finding themselves. This is the exception to what we were talking about earlier where we're rooting for these women but, as far as I know – I'd be interested to know if there are exceptions – none of them have children at that point. I'm wondering if that makes the difference. You made it pretty clear that if there is any redemptive arc to be found in your story, it's not the kind of thing you can really write about because it's the work of a lifetime and how do you even capture that? So do you think that's about having children? Do you think it's harder to frame a woman figuring herself out and finding that fulfillment as redemptive when there's more fallout than just a jilted husband?

Well, obviously we live in a culture where women's narratives conceptually seem to end with marriage and motherhood. There are a lot of amazing memoirs by women that cover many daring things they've done in their lives but they do tend to focus primarily on younger women, even if they're not written when the woman is young. The misadventures or the misspent youth or the mistakes of youth and then there's some sort of cleansing or healing, and then at some point in the future or in the book, the woman then marries and has a child. Obviously, I think in the good books of this nature, there isn't any implication that somehow now there's no story ever after this but there are an enormous number of memoirs by women that do end with marriage and children, or the implication of soon-to-be marriage and children. I’m middle-aged, I'm 52. The events of the memoir unfold primarily in my 40s and end when I'm 50 and I've been a mother since I was 32. And certainly I'm not the only one who's done it but I do feel like there are not enough stories out there of middle-aged women who basically- things go off the rails. Of mothers who have a massive change in their lives by their own making. And I think our culture of course desexualizes mothers, desexualizes people who have been ill. At the beginning of my narrative, I haven't had breast cancer yet, I haven't had a hip replacement yet, but those things happen as the text goes on. And I, as a reader and as a writer, and as a woman, am frustrated by how few narratives there are about complex middle age and about mothers making mistakes and still being human and still having a relationship with their children and their children still being the most important thing in the world to them even though they’re not perfect. You get to a certain age and most of the memoirs you’re reading are not really about you. And I don't mean that like middle-aged women are all necessarily getting divorced or having affairs or having breast cancer or any of these things, but they're just not about people our age.

There’s a lot of things that can happen in those years and we're so used to taking what publishing gives us in terms of narratives about women.

Yeah, I'm really thankful to Counterpoint for really embracing this. Not just embracing the story of a complicated middle-aged woman, but also encouraging me to really embrace cultural criticism, feminist theory, to really make it a story that isn't just about me. I had worried that people would be like stop talking about Cixous, nobody wants to read that, and instead Dan Smetanka was just like, go crazy, keep going, just push it as far as you want to take it. So that was really amazing.

Order Blow Your House Down and Gina’s novels here.