Back when Fleishman is in Trouble first published, Taffy Brodesser-Akner wrote about the curiosity we feel when we hear about divorce, the desire to know what went wrong and how bad it was so we that we might determine whether that same thing is going wrong in our own marriages, whether we’re also persisting in a similar badness and holding onto something we shouldn’t. Amos Oz once said that literature is a cousin to gossip and both allow us to peer into the lives of others and measure ourselves by their yardstick, hopefully reassuring ourselves that we’re doing ok. Perhaps this is part of the reason I’ve enjoyed so many fictional and nonfictional and autofictional treatments of divorce lately, but I don’t think it’s the whole story. Or, I think the specificity of my curiosity has as much to do with writing as it does with marriage.

It’s tricky because it is the writers who are best equipped to let us in on the secrets of a marriage’s demise and that means that some of the most beautiful and compelling divorce stories are the ones that feature writing as one of their central concerns. I’m thinking of the gorgeous You Could Make This Place Beautiful by Maggie Smith, who writes that her husband treated her writing work like an interruption of her domestic obligations. I still think about Maggie’s description of her ex’s lawyer using air quotes when talking about her writing and writing-adjacent work (“when you were ‘working,’ she said”). There is also the forthcoming Liars by Sarah Manguso, narrated by Jane, a talented writer married to a less talented artist and overburdened by domestic responsibility. “Then I feared that trying to stay a writer would render me unrecognizable, just burned to a husk by frustrated rage,” Jane relates. “That was the one part of my life, I thought, in which I could exercise choice. Wifehood and motherhood were unassailably permanent, I thought.”

I’m also thinking of Alba de Céspedes’ Forbidden Notebook, which I (somewhat surprisingly) finally got to over my kids’ winter break. It isn’t technically a divorce novel but it features a protagonist who, in writing about her life in the titular notebook, comes to the realization that she has become fully subsumed into the burdens and expectations of marriage and family, that she isn’t free.

Of course, being free (or feeling free, or getting free) is a fixture of divorce narratives, whether they’re professionally bound or told over brunch. In these books, that freedom – or its absence – is linked with writing. Part of it is the childcare aspect – how do you find time to write when time costs money and writing too often makes very little of it? But there is also the question of the autonomy we may or may not relinquish when we bind ourselves to another person: do they get a say in when and how and what we write? (Remember this essay?) What happens when success for the writer in a relationship isn’t a shared goal?

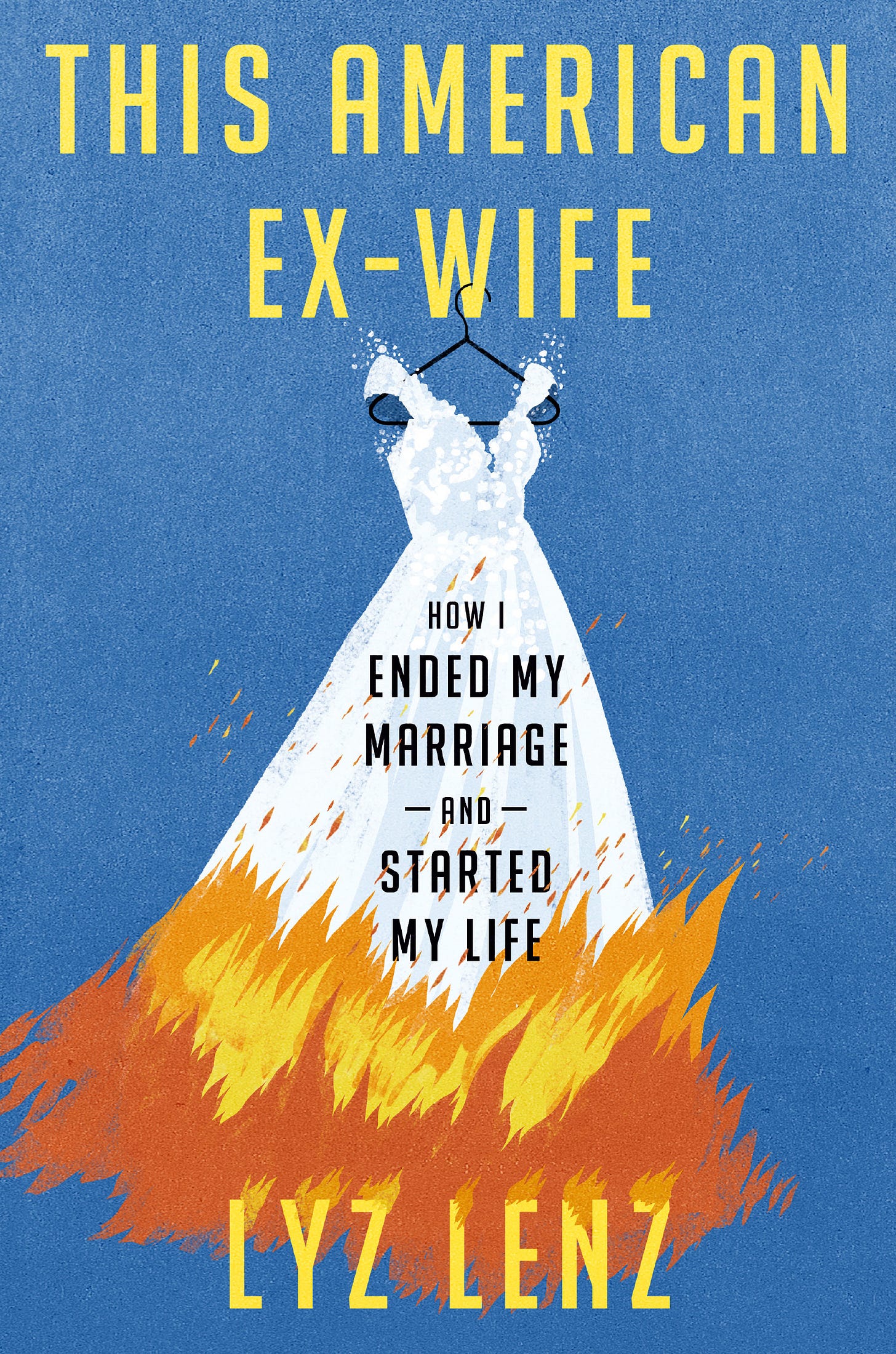

In This American Ex-Wife, Lyz Lenz’s incandescent new book that you’re going to want to preorder immediately (it publishes 2/20), she writes, “It soon became clear that I could be successful or I could be married.” In couples therapy, Lyz would ask for help and her husband would ask her to do less writing. Was this request about domestic responsibility or about art? Read on for my conversation with Lyz about the impact of shared custody on her work, men having feelings about women writing, and divorce freeing her to finally tell the truth.

Lyz, I have to point out that you've been really prolific for a mom. You've published three books since 2019. Is it because you got divorced? Kind of, right?

Well, there are a couple things happening. I started writing God Land in 2017 and my kids were very little and that was the year my divorce happened. My kids were six and three when everything was splitting up. And I was trying to write the book and I was their primary caretaker so I had a lot of mental energy going into not falling apart. I was falling apart. My life was falling apart and America was falling apart, and then I had to wake up at five every day with my small son who still likes to wake up at five even though he's ten but now he can just go get ready for the day and play on his Switch instead of crawling into bed with me and telling me about all his dreams, which is sweet, but also annoying as hell. And so yes, in order to write my first book, I had been writing in snatches and bits and had all this information, but I wasn't able to pull it all together until I left my family for three weeks to go to a writing residency, which was a very long time to leave small children. And I felt awful and terrible, and I still kind of feel awful and terrible about it, although my kids don't remember now.

Do you, though? You couldn't have written the book otherwise.

No, I could not have written the book. I had pieces written, but I basically put it all together in a month. And then the editing process took several months after, but it was basically wake up at five, go for a little run, come back, sit, sit, sit until my back hurt, go for a walk, sit until then I felt like my brain was bleeding out of my ears by four. And Belabored was written in a similarly stolen space of time. When I was writing Belabored, I was split up from my husband and during the day, my writing had to be the writing that earned me money. So I was ghostwriting op-eds, I was writing marketing property, doing a lot of writing that made money, but at night I would put my kids to bed and basically I'd make myself a big pot of tea and then just drink it. And I almost didn't write Belabored because it was so hard to find the time to do it, and I didn't get a very big advance for it. I got like $3,000, and even though I was so broke, I remember being like, ‘I could just not write this book.’ But I had a friend whose wife had died, the writer Matthew Salesses, so talented, and he was like, ‘Just write your fucking book.’

It's good to have friends like that. He also told you to get divorced?

He did.

I figured that was him in the book. So we owe him a lot, I guess.

Yeah, he's just out here ruining my life, and now he's moved far away, so he can't ruin my life anymore. And he is remarried now. That book was written basically between 10 PM and 2 AM at night, and so I'd get the kids down and I would just get into the space. I turned off the internet at my house. I'd go unplug the Wi-Fi router, and then I'd just sit down and it'd be like, ‘If you get 50 words down, that's 50 more words than you had yesterday. Go, go, go, go.’ And then the book appeared and with this-

Well, can I ask about that though? Because you were divorced already and had shared custody, was there time where you weren't with the kids and could write at normal times? Because that's incredibly hard to keep up only writing 10 PM to 2 AM.

Yes, right. And so I had time to recover, but I wasn't really writing a lot on the weekends because I was still trying to catch up with paying work and stuff like that too. But I will say when I was writing Belabored, I had more of that psychic space. During the day I had more of that time to think about it because I wasn't so occupied with the daily concerns. I wrote about this in This American Ex-Wife, all of a sudden my house was cleaner. There weren't as many dishes. There were so many nights where I did not have to worry what am I going to cook for dinner? I'd just eat cheese over the sink and then go write. I could be an art monster-

Because your kids were with someone else.

Yes, and I knew they were taken care of, and I didn't have to worry about that. And it was like all this space in my head- a psychic weight was just lifted off my shoulders and I could just focus on this thing. And I felt it even more with This American Ex-Wife because I was finally not so broke when I wrote the book because I got paid money for that, so another kind of psychic weight got lifted off my shoulders. And I think there's a couple things. I am a little bit of a maniac. My mental illness tends to be more towards the manic side of things, and so let's not discount that, right? But yes, it was also, I think because of divorce and having all of a sudden- I wrote in that article for Glamour and I wrote in This American Ex-Wife, having shared custody was a revelation that I did not expect in clearing up space in my mind to write and think and do work in a way that I had never really been able to before except for college.

Sometimes I joke about getting shared custody and somehow staying married, which I guess means I feel like I’m carrying too much of the load.

That's one of the reasons I wrote the book. Not to say to every couple to get divorced, which, whatever, but to say this is a conversation. This is actually what equality looks like. And I think we struggle so hard, and especially with the pandemic, which put so much more weight on women. And there are a lot of men who do not know what equality looks like, who I think want equality in their relationships, but we just don't know what that looks like. And so to be able to say, ‘Okay, this is actually what it looks like: 50/50. These days a week, Monday, Tuesday you do dinner, you do school pick up, I am art monster.’ And that is what it looks like, and that is the goal, to get there. And I think that will not break a good relationship but it is going to break a lot of relationships. And I think that's what is so frustrating about asking for equality in a marriage – and I think a lot of women know this – that if you actually asked-

There's a risk to it.

There's a huge risk. It could break apart your life. I heard Glennon Doyle Melton say this thing in an interview with Celeste Ng where she said, ‘Women don't ask for what they want because they know they might not get it, or to get it means wrecking your life’. So part of why I wanted to write this book was to say two things: one, ask for what you need and what you want. It doesn't have to wreck your life. But two, if it does wreck your life, that's okay. Maybe your life needed to be wrecked, and that's a fine thing too.

100%. But I’m wondering, is there also a divorce-specific mental load? You're obviously much more free now, but is there a different kind of coordinating responsibility that comes with sharing custody?

Yeah, it's far less. It's so funny because- and I'll say, to be very fair, I think my ex would vehemently disagree with this, but I still do the calendar. Every year, two weeks before school starts, I take a couple days off from work, literally it takes me two days because this is not what I'm good at, by the way. Organizing is not what I'm good at. And I have to take two days, and that's when I get all the piano lessons and everything on the calendar, figure out the swim schedule, figure out soccer. Figure out who's got what and pickups and all this kind of stuff and get it into the Google calendar. It's a huge load and it still remains. There are still some things that continue to remain.

My breakdown this week has been that I want to be in charge of fewer things because this time of year, it's gifts, family members asking, ‘What do the kids want?’ And then that's a job, what the kids want. One kid has a birthday, I'm planning the birthday party. All those things. And I don't want to be in charge of so many things but I can't imagine that going away because it's so entrenched. We're raised to be in charge of those things.

I'm still learning to let things go. I remember when we first split up and my ex had texted me, he's like, ‘Well, I don't have snow boots. Can you run some over?’ Because of course, I'm the one who had the snow boots because I am the one who's prepared for snow.

You live in Iowa.

Yes, I live in Iowa.

Snow happens there.

My therapist was like, ‘No, stop it. Let that go.’ Because I was like, "’Well, I can't let it go. What if they don't have snow boots?’ She's like, ‘That's his problem. That is his house.’

And that's how you learn.

And that is how you learn. And I think there are two things happening, right? One, we want to create these lives for our children that are organized and that always have snow boots available whenever they need them, but there are also ropes that we cling to that we can let go. And that I think that letting go of those ropes, that's what my agent talked about when she read the book proposal. She was like, ‘it's about letting go of the ropes that we cling to, that we think we have to hold onto because the standard for American parenting is stupidly high.’ We've all seen the statistics. We parent more intensively, even though we have full-time jobs, than mothers did in the 1950s and '60s when they weren't working full-time jobs. And so a lot of it is just letting go and knowing that your kids are going to be okay, and resetting those bars and standards so that you can be a full human being and not just some fucking Google calendar. I think one thing in the pandemic that I had to learn to let go of, because I did it for me out of my own childhood trauma, but I'd have these crazy parties for my children and then I realized they don't want the parties, I want the parties. And then of course, pandemic was a great time for me to just let go of that. And now my kids are older, and now when my mom texts me and says, ‘What do the kids want for Christmas?’ I say, ‘I don't know, Mom. Ask them.’

Ask them, right. You can do that with older kids.

But I think life as an American woman is a constant process of being told you need to carry everything and then once you're carrying everything, learning to let go, and that's freedom. And learning that these beautiful, precious children are okay, and part of them being okay is seeing us be full humans and not just parenting artificial intelligence robots, that we get to be full humans because that's modeling to them that later they get to be full humans.

They can do that, right. I do want to talk about the arc of your career because my sense is that you built it from the ground up in a way that's very common, but not very commonly talked about. You started out blogging, and then your first book was with an academic press, and your second book was with a bigger press with a low advance, as you said. And so can you talk about doing that building over all of those years?

Yeah, I think when I was in college, I thought I was going to be a lawyer, and so that was the career I was preparing for. And I didn't show up to the LSATs because I didn't have a car and my ride was my sister, who we had a big family falling out where the short of it is that my brother-in-law had been very violent and all of this was coming out, and my sister was in a bad place and I just didn't get to go to the LSATs. And that family trauma kind of tore my life and my ambitions and my goals apart a little bit my junior and senior year of college, and then what ended up happening was just I got married and moved to Iowa. I'd had a lot of college professors be like, ‘You should try to write, this might be a thing.’ Not a lot. I had one. There was no Greek chorus.

You only need one.

It was just the one woman who was like, ‘You should try this,’ and she forced me into her senior seminar.

She was right.

She was right. Becky Fremont, a beautiful poet and goddess, was right, of course. And so then I was floundering in Iowa and writing was the thing that, of course, as I think for so many writers, brought narrative structure to my life, helped me make sense of my life, especially at this really difficult time as I'm trying to understand how my family had fallen apart and what was going on in the lives of my sisters. And so I started Googling how to become a writer. This is like 2005. And I'd apply for jobs and then Google how to get published, how to send a pitch letter, reading all these Publisher's Weekly forums with people, and then reading Gawker every day being like, ‘I want to be them,’ participating on Jezebel. And I also had this little blog, and I've had various blogs ever since college where I'm furiously writing and furiously trying to find a voice and meaning. And then it started to snowball. I got this job at a website called YourTango, which still exists, and they're still lovely supportive people of my career. And I worked for them for a while and then I went to graduate school because I was like, ‘Well, I should be able to teach maybe.’ But then I graduated in 2008-

That's a real moneymaker.

Right, it was like, now I'm just adjuncting across the state and then pregnant and it's a nightmare. And at some point, my now ex-husband was like, ‘You are losing money with gas.’

I've been there. Paying someone to watch my child while I adjuncted – a losing proposition monetarily. And also professionally.

And so I didn't go to journalism school, I didn't do a lot of things that I think more traditional career paths can take. But I also don't think it's untraditional for a woman who is a mother to build up a career and a life. And I think a lot of it is just making a lot of friends and having people believe in my writing and discover my writing. And I've always had this mantra, ‘go where people like you.’ So if I send a pitch to a place a couple times and never hear back, then it's like, ‘Well, maybe they don't like me.’ But the people who do like me and understand what I'm doing, those are my people and that's where I will go, and I don't have to waste my time being sad about the rejection, although I still get sad. I was sad the other day about a rejection.

That’s validating.

Modern Love. Come on, guys. What’s a girl got to do? But just finding those people who will champion your work. And I think every big break I've ever had came from a friend telling an editor, ‘You should have Lyz write this.’ So that's the career trajectory and it feels so nice to be where I am now, but it wasn't that long ago where I'm doing interviews on the phone for stories for the Daily Dot while I'm at the park with my two-year-old son who's chewing my leg and I'm throwing goldfish crackers at him being like, ‘Shhh.’ I remember transcribing interviews listening to and hearing Curious George playing at full volume in the background and being like, "Oh God, I bet the"-

They could totally hear.

It's just like, ‘Oh God. Oh God.’ I remember doing an interview once for The Huffington Post. They did that Huffington Post live thing and I was like, ‘Oh, I'm going to be so famous, because I got on the Huffington Post live.’ And I just had my son, so it was like milk boobs and I told my now ex-husband, ‘Okay, just take the baby. Just hold him for 30 minutes.’ He was such a fussy baby too. And I'm doing it, but of course I did it so that you couldn't see my boobs but then the baby starts crying and my then husband holds him up to the office door, which had these glass windows as he's screaming, and I'm like, ‘My milk's coming in,’ and it's leaking through my shirt, so I'm doing this interview just going scooch, scooch, scooch. I remember reading something about Toni Morrison, the reason she wrote poetry in the early part of her career was because that's all she had time to write. And I remember hearing that and just really taking that to heart and just being like, ‘Well, you just do what you have time to do.’

Well, that husband story brings me to my next question. You write in This American Ex-Wife that, as your marriage was unraveling and you were writing God Land, you realized that you could either be successful or you could stay married. This book is about many things and one of them is the dynamic of a woman wanting to write and a man having feelings about it. You talk about how he suggested that you just write mystery novels and not be a journalist. Was that a logistical thing? Did it have to do with what you were writing about in that book?

That's a great question. I think if you had asked me this while I was married, I would say it was just all logistics but once I was out of the marriage, I realized how much I hadn't been saying because I really wanted to protect that relationship. And I think once I got divorced, I heard from so many women, and I know I put this in the book and that's why I have those little interstitial stories because so many women would say, ‘Here's my story. Here's what happened to me, but you can't write it or use my name because it will ruin the relationship. It will ruin that tenuous thing that I'm still trying to hold on to.’ Even post-divorce, a lot of women were like, ‘It will just make him so mad.’ And I think that was one of those realizations that, again, if you had asked me in my marriage, ‘What's holding you back?’ I would just be like, ‘Oh, it's just time and logistics,’ and then once I got out, I realized all the things I was not saying.

I’m interested in all that, and particularly because with God Land you were writing about religion in middle America, and I think a lot about how the angel of the house persists when you are writing as a woman who was brought up in religion or in a faith community because the angel is not just a roadblock to writing because she’s good at keeping a house. It’s not just like, ‘Oh, you should be folding the laundry,’ or whatever. It’s also that she has ideas about what’s appropriate and not appropriate for a woman to write. Do you think your ex-husband wanted you to write novels because he felt that that was safer, less challenging to certain structures?

Yes. When I got my MFA, it was in fiction. I wrote a lot of novels. I have three novels in a drawer, meaning on my laptop. I had this professor, he passed away, but it was this Jamaican writer, Wayne Brown. And he was reading all my writing, and he looked at me one time and he was like, ‘You know why you write fiction?’ And I was like, ‘No, I'm 25, I don't know anything.’ He's like, ‘Because you're afraid to tell the truth. All writing is truth-telling but you're not telling the truth. I think you're afraid of the truth, so your writing is not going to ever be good until you start telling the truth.’ And I didn't really understand what he meant until I got out of my MFA and I started writing this book that I called The Women We Were Supposed to Be, and I was like, ‘It's going to be about religion and feminism and all these different versions of womanhood.’ And I wrote this book, and I couldn't get an agent for it, nobody liked it. And even when I got an agent, she was like, ‘Something's not working here.’ And even parts of that book I still tried to put in this book, my editor was like, ‘It's not working. Take it out.’ And so, I think there is an aspect of the writing that my now ex wanted to ignore. And I don't want to just put it on him. A lot of the men I have dated have a problem with my writing. They don't like it. Even if I've dated writers, writers don't like it that I’m- the few times I have dated writers, I have been more recognizable than them in my writing and I think that's just because I have a very specific niche. Sadly, I would like to trash their writing, but they're both very talented writers. Sadly.

My condolences.

Bad people, just shitty humans. But no-

Fine writers.

Fine writers.

It’s so sad when that happens.

It's the worst. But I do think, and I've talked about it with other female writers too, that there's a little tension when you are a woman who publicly has a forward-facing job and a voice, and you suddenly have this platform where you get to say the truth of your life. It's not just my ex-husband who has a problem with that. A lot of American men have a problem with that, and I don't know the answer to figuring it out. I recently started dating somebody who was like, ‘Well, I don't know how to handle your writing.’ I was like, ‘I don't know how you handle my writing either. I don't know why it has to be something you have to handle.’

How have women handled men writing? We've had a bunch of centuries of male writers, so maybe we could just follow that playbook.

Right. But it's so different, I think.

What is it? What do you think it is?

We don't want a woman who we can't figure out, we don't want a woman who is not within our control. Even women who write novels still get the, like, ‘Oh, you had a sex scene. What does your husband think about the sex scene in the novel?’ Or, ‘Oh, your book is about a mother. Was that based on your experiences?’ Right? And I think we don't know what to do with an unruly woman. We don't know what to do with a woman who does not fit in the box, in the little straitjacket we have made for women. And when you fall outside of those binaries, when you challenge the boxes, when you say, ‘No, I don't want to be in there and I don't fit in there,’ I think it really unsettles people in a way. So we’ve just got to figure it out. Meanwhile, we have a lot more tolerance for male genius where it's just like, ‘Oh, it's Philip Roth. He's not really Philip Roth.’

It's so hot.

Yeah, it's so hot when a man is so talented. And I think a lot of people think a woman is hot when she's talented until they're in a relationship with her, and then it's very threatening.

I wonder what kind of man it takes for a woman to be able to tell the whole truth.

I don't know.

Or if you just need to dispense with the man if you want to do the truth-telling.

Or do you just need a Travis Kelce who just, like, doesn't care. He's been hit in the head so many times. He just wants his Chipotle and to look at the stars. I don’t know what it takes and honestly, that’s not my driving goal. I’m not gonna figure that out for men. But there is something and I don’t know if I’ll have the same answer in a year that I have now.

We’ll check back in.

I know I put this in the book but when I was pitching the book- like you said, I've been so lucky that I have been able to start with an academic press and go to Crown. It doesn't always happen like that and I think it's just luck, chance, and culture, a lot of things that are out of my control. But trying to pitch this book, there was resistance, and this was in the rarefied halls of educated white publishing in America where I got an editor being like, ‘Well, have you had a successful relationship since?’

Yes! The whole ‘Do you have a man? Because that would make this a lot easier to sell,’ which is crazy. I couldn't believe it when I read that because you not telling that kind of story is the value of this whole book. I can think of many books that are well-written, compelling, that have that arc of, ‘I had a bad relationship and then I found a good relationship.’ I don't know that I need to read another one. There could be another one that I'll enjoy, who's to say? But this is new and different and necessary. And so I wanted to ask you about that because it made me think about how intertwined success as a writer is with that idea of a happy ending or what we consider to be a happy ending – the happy endings that we're comfortable with.

That we're comfortable with.

Where you can only critique something if it all turns out okay. You can have a radical message, but people are only going to take it seriously if in the end you fall in line.

That's every divorce story, and that's one of the reasons I really wanted to write this book. And I don't think I would have been able to publish this book if the pandemic hadn't happened, if it hadn't broken America open in a way that made people think, ‘Okay, we need something more and better.’ And now I can kind of feel the cultural conversation closing up again, and I feel like I got to sneak this book in at a very specific moment in time. And of course, my agent very brilliantly knew how to sell it to a more uncomfortable crowd. But that kind of, ‘It has to end okay,’ feeling, I get it every time I talk about the book, it doesn't matter- actually, the 80-year-old Midwestern grandmas are more, ‘Hell yeah,’ about it than the 40-year-old publishing executives. You're right, it makes people nervous if you say, ‘I don't want to preserve this institution of marriage, I want to kick it over, I want to criticize it. If it's bad, fine.’

Those grandmas have nothing to lose.

That's it, and that's what I think. I was reading all these divorce books and they were either like, ‘I was abused and I got out-‘

In which case we say, ‘Good. Okay, yes, I want that for you."

But it's very specific.

It has to be bad enough.

It has to be bad enough to justify it, and then other people can read it and say, ‘Oh, well, my marriage is fine.’

Right, ‘I could never.’ That “good man” that you talk about in the book.

Yes, that never happened in my marriage. He is a good man, I just didn't want him. I just didn't want it. And I think that makes so many people uncomfortable. And one of the things about divorce is that it has a ripple effect. There's been many studies that show that if one person in a close group gets divorced, then that can have a ripple effect. And people call it contagion and I'm like, ‘No, it's showing other people how to get free.’ That's what it is, and that's what makes people so nervous about it.

It makes people very nervous. My parents got divorced when I was already an adult and, suddenly, other women were coming up to my mom and saying, ‘Should I get divorced?’

I call it the Lilith Effect, where it's like you escaped Eden and all these women want to know, ‘Should I leave Eden too? How bad did it have to be?’ So I'm reading all these divorce books that are either personal memoirs that are horrific or they're about how to find love again, and I don't want any of that. I don't want love again. Kind of, but not really.

It depends, right?

But I also am fine, and I'm sick of self-help. And this is a problem with growing up in a religious home, is that all self-help sounds like a sermon now so I have no tolerance for any sort of level of self-help, even though I'm a hot mess. There’s so much about divorce that's like apologia, right? ‘Well, it was so bad I had to do it.’ There's never anybody just being like-

I wanted to.

I wanted to. And happiness is worth it because there's this narrative out there that's like, ‘Well, people treat marriage like it's fast food and you can just throw it away.’ It's not true. It's easier for a 16-year-old in America to get married than it is for a 41-year-old woman to get divorced. All the cultural messaging about it is, ‘Well, how dare you put your own happiness above that of your children?’ And we're seeing it right now too. I think 2023/2024 is going to be a bad year for it. There is nothing in American culture that tells women that, actually, your happiness is worth it, and I wanted to just write that book. And I wanted to write it that it has a happy ending, but that the happy ending is not another relationship, the happy ending is community. The happy ending is peace and being able to be fully myself in a way that I've never experienced before because I grew up in patriarchal religion, I got immediately married, and I just have never been able to have this kind of life, this kind of freedom.

Everybody's looking for stories or a version of a story that they've read before. Maybe we're scared of new kinds of stories. And I’m wondering whether you think a rejection of the old ones, a rejection of marriage and embrace of freedom for women specifically might impact a creative woman's ability to find an audience.

We love the stories that make us feel comfortable. And I do sometimes joke with friends that if I was a man, or if I was married again, I might be more successful.

That's a real thing, right? It's hard to make money as a writer. No matter how much success you have with this book, there's going to have to be another book. And I can imagine it could be scary to go into that without having what that comfortable story, that “having a man,” lends you in terms of-

The covering and the air of respectability. You talk about me being nervous, I think what I'm more nervous about is that people will just ignore it instead of taking it seriously. I'm not nervous about backlash, I'm nervous about silence. I've endured a lot of backlash, very violently so and I don't want to downplay it, but I do want to say what is worse is the way that we memory hole and pigeonhole these stories. Because one thing about the writing process for this book was I realized how many women have done and said exactly what I am doing and saying. I am not original. How these women have just been lost to history or we downplay their stories, or we make them seem like these crazy fringe freaks. You know, ‘that was just Ursula Parrott and she was kind of a drunk.’ When I was writing this book, I felt like I was building on a tradition of women like Simone de Beauvoir, all these women- this is not my lane, but even Sojourner Truth, when formerly enslaved people were getting more rights, she was out there saying, ‘I don't think we should be participating in the American institution of marriage because it is another form of slavery.’ She said it more eloquently and strongly and forcefully than I ever have. So I am not saying anything new, but wow, we sure do love to forget the women in history who have said this and who have advocated for their freedom. And that's why I began the book with the quote from this woman Blanche Molineux. Her story is written about in April White's book, Divorce Colony, but I wanted it to be a woman who's kind of been forgotten in history, a woman who accidentally became a pioneer for rights because she just wanted to be happy and wanted to be free. So what I am more afraid of is that pigeonholing and that burying under the ground, and let's just forget this ever happened because if we take these ideas seriously, I think they do challenge the very foundation of how we have built our tax-base.

I think it's a serious challenge to the status quo, and that's something that people don't readily accept.

And I think, too, one thing I'm worried about is they're just going to be like, ‘Oh, she's bitter.’ And I'm like, ‘Maybe a little bit. There's nothing wrong with being bitter.’ But also really happy. When I was talking about the book and writing it, I was like, I only want a very small section of the beginning to be about the actual divorce. I want the rest to be about post-divorce. I want it to be about building life. I want it to be having sex. I want it to be about talking to my kids. I want it to be about moving to my home and burning the dress. I want that to be part of it because I want people to see the other side.

Preorder this 🔥 of a book here.

An absolute force of a conversation. I was breathless. I can't wait to read this book! Men cannot stand women writers, because men cannot risk being around women who tell the truth, unashamed.

Oof. This really hits home for me “ I recently started dating somebody who was like, ‘Well, I don't know how to handle your writing.’ I was like, ‘I don't know how you handle my writing either. I don't know why it has to be something you have to handle.’” That’s been so many of my relationships, and it truly discouraged me from writing at all. I’m embarrassed to admit that.